Learning to Write a Python SDK Library for ChatGPT API from OpenAI

0 CommentAfter ChatGPT was released, OpenAI open-sourced the Python library openai-python for model invocation. This library is very comprehensive, encapsulating the APIs published by OpenAI, and is also very simple to use.

OpenAI-python library encapsulation

OpenAI-python library encapsulation

The first version of this library implemented Python abstract classes and invocation methods for parameter encapsulation of various ChatGPT APIs, using the requests and aiohttp libraries to send synchronous or asynchronous HTTP requests. Overall, the external interface is good and easy to use. The overall source code implementation has good logical abstraction, using many advanced Python features, and the code is beautifully written, worth learning from. But essentially, this is still “API boy“ work, more of repetitive manual labor without much technical content.

So, in November 2023, OpenAI began introducing Stainless, eliminating the need to manually write SDK code. Each time, they only need to provide API protocol updates, and then code can be automatically generated, freeing them from repetitive manual labor. Specifically, new code was introduced in Pull 677 and released as the official V1 version.

Manually Crafted SDK

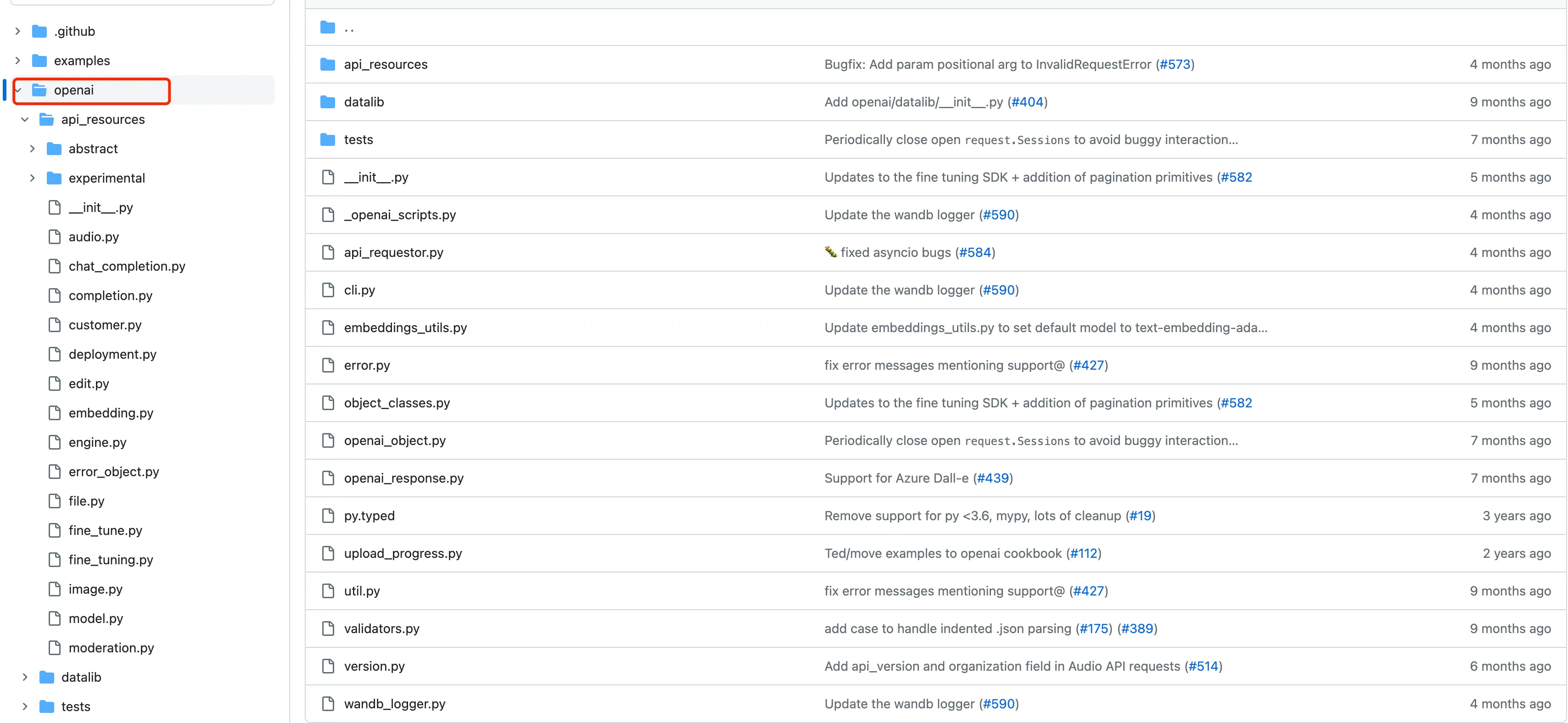

The initial Python SDK can be called a manually crafted SDK, with all code written by hand and coupled with the API. The overall directory structure is as follows:

Old code version of openai-python library

Old code version of openai-python library

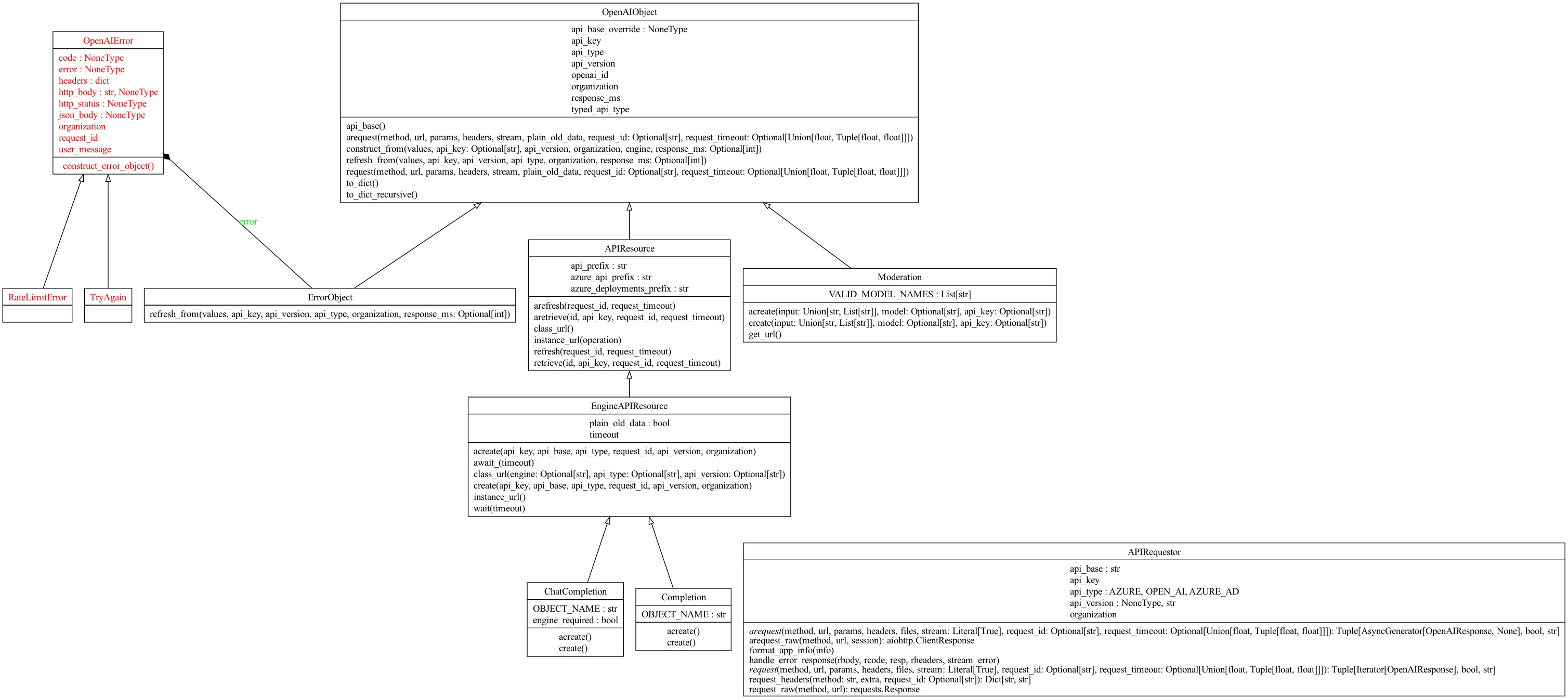

The overall structure of this version of the code is relatively clear. I used Pyreverse and graphviz to generate a class diagram for the openapi-sdk. After removing some unimportant classes, the overall class dependency relationship is as follows:

Core class diagram of openai python library

Core class diagram of openai python library

There is a basic class OpenAIObject, which defines some basic fields, such as api_key, api_version, etc. The ChatCompletion class we commonly use indirectly inherits from this class. There are also two classes, OpenAIError and APIRequestor, used for handling errors and sending HTTP requests respectively. OpenAI’s code uses quite a few advanced Python features. Here we’ll take the overload decorator as an example to look at in detail. Of course, if you’re not interested in Python, you can skip this part and go directly to the automated generation section.

overload Decorator

The APIRequestor class in openai-python/openai/api_requestor.py has many methods decorated with overload, which is a new syntax introduced in Python 3.5, belonging to the typing package.

1 | class APIRequestor: |

In Python, methods defined with the @overload decorator are only used for type checking and documentation, they are not actually executed. These overloads are mainly to provide more accurate type information, so that when using static type checkers (like mypy) or IDEs (like PyCharm), more accurate prompts and error checks can be obtained.

Using @overload can more accurately describe the behavior of a function or method under different parameter combinations. The actual implementation is in the request method without the @overload decorator. This method usually uses conditional statements (such as if, elif, else) or other logic to perform different operations based on different parameter combinations. The 4 request methods decorated with overload above actually define 4 different methods, each accepting different parameter combinations and returning different types of values.

Explanation of the request parameters above:

files=...: Here, files=… indicates that the files parameter is optional, but the type is not explicitly specified. In Python’s type hints,...(ellipsis) is usually used as a placeholder, meaning “there should be content here, but not yet specified”.stream: Literal[True]: Here, stream:Literal[True]indicates that the stream parameter must be the boolean value True. The Literal type is used to specify that a variable can only be a specific literal value, which is True here.request_id: Optional[str] = ...: Here,Optional[str]indicates that the request_id parameter can be of type str, or it can be None. Optional is usually used in type hints to indicate that a value can be of a certain type or None. The= ...here is also a placeholder, indicating that the default value has not been specified. In the actual method implementation, this would usually be replaced with an actual default value.

Here’s a relatively simple example. Suppose we have a function add that can accept two integers or two strings, but cannot accept an integer and a string. Using @overload:

1 | from typing import Union, overload |

The benefits of adding annotations are:

- Type checking: After using

@overload, if you try to pass an integer and a string to the add function, static type checkers will immediately report an error, without waiting until runtime. - Code readability: By looking at the

@overloaddefinitions, other developers can more easily understand what types of parameters the add function accepts, and the return types in different situations. - IDE support: In IDEs like

PyCharm,@overloadcan provide more accurate auto-completion and parameter hints. - Documentation:

@overloadcan also serve as documentation, explaining the different uses of functions or methods.

For the add function above, if you call it like this: print(add(1, “2”)), mypy can detect the error without waiting until runtime:

1 | override.py:22: error: No overload variant of "add" matches argument types "int", "str" [call-overload] |

Introducing stainless for Library Refactoring

The above is a more traditional way of generating Client code based on API interface definitions. In fact, the daily work of many programmers is similar to this, providing various parameters for APIs and then calling them, or providing interfaces externally, which is the so-called API boy.

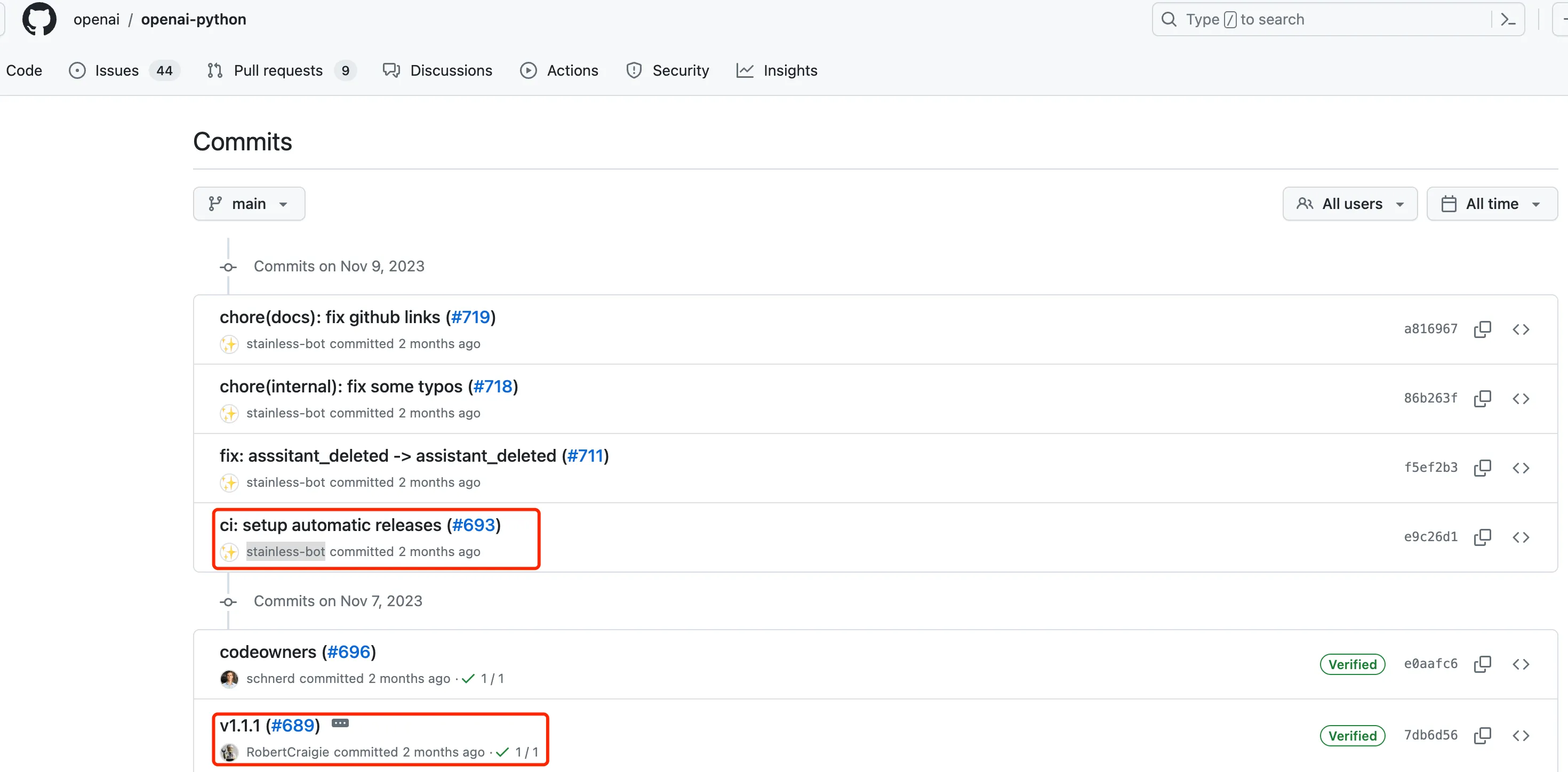

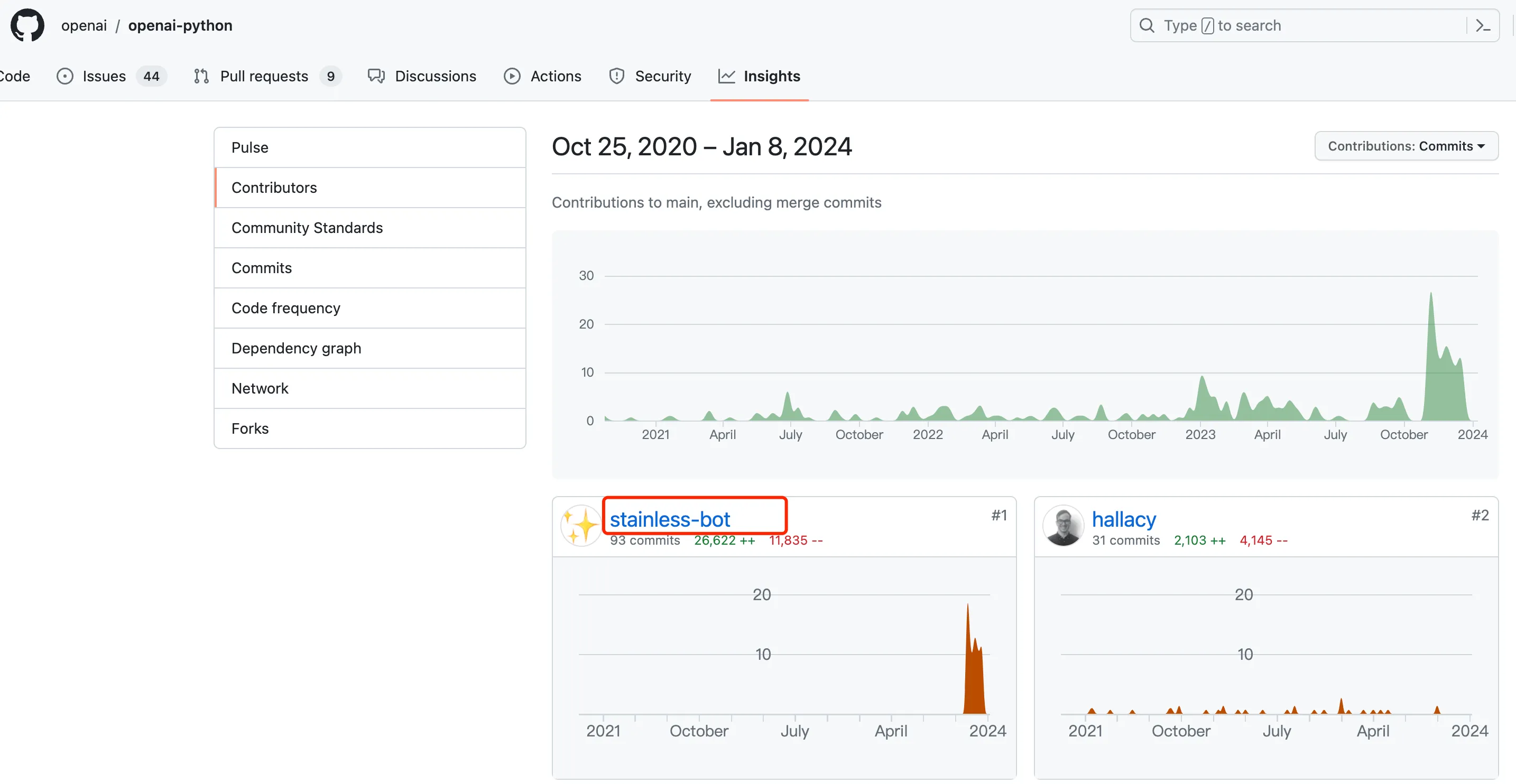

OpenAI’s programmers, obviously not satisfied with being API boys, made a significant change in V1 in 2023.11, as can be seen from the repository’s commit history. They started using stainless to generate code, and subsequently introduced the stainless-bot robot.

Starting to introduce the stainless-bot robot

Starting to introduce the stainless-bot robot

stainless is an open-source API SDK generation tool that can automatically generate corresponding code based on API protocol definitions. You only need to provide the API interface file, which is the OpenAPI Specification file, and then it will generate SDKs for various languages. Currently (as of 2024.01), it supports languages such as TypeScript, Node, Python, Java, Go, Kotlin, etc.

The quality of the generated code is also guaranteed. According to the documentation, it tries to make the automatically generated code as good as code written by expert-level programmers. The generated library also supports rich type checking, which can be used for auto-completion and documentation prompts when hovering over code in IDEs. It also supports automatic retries with backoff, as well as authentication. Every time there’s a new change in the API interface, you only need to update the API protocol definition file, then push it to stainless using Github Action, and it will automatically generate new code and provide a Pull Request for your repository.

It sounds great - you only need to change the protocol, and then you have generated code. The entire process doesn’t require people to write code, and there’s no repetitive manual labor. Let’s take a look at the recent commit records of OpenAI’s SDK. Basically, all the code is now committed by stainless-bot.

stainless-bot robot becomes the main code contributor

stainless-bot robot becomes the main code contributor

There’s still a question here. The stainless-bot update feat(client): support reading the base url from an env variable supports reading OPENAI_BASE_URL from environment variables, but I didn’t see any related explanation in the API spec. I’m not sure how this update was generated by stainless-bot.

It’s also worth noting that this refactoring broke compatibility, changing the way the library is called, so old version calling code needs to be changed. OpenAI also provided a migration guide document v1.0.0 Migration Guide, and provided an automated migration script for one-click migration.

OpenAPI Specification

According to stainless, the basis for automatically generating code is the OpenAPI description file. The specific protocol can be referred to in the documentation OpenAPI Specification. OpenAPI is mainly used for designing, building, documenting, and using RESTful Web services. It provides a standardized method to describe RESTful interfaces, making it convenient for developers to define API request paths, parameters, responses, security, etc. in YAML or JSON format. With the description file, you can automatically generate human-readable documentation, create automated tests, including generating client SDKs, etc.

The API definition of OpenAI ChatGPT is also open source, in the Github repository openai-openapi. The API interface definition for version 2.0 can be seen here.

Let’s take the /chat/completions interface as an example to see what content needs to be defined for an interface. First is some metadata:

1 | paths: |

Here, post indicates that this interface supports post requests, operationId is the unique identifier for this operation, tags categorizes this operation as “Chat”, and summary provides a brief description of this operation. Next are some key constraints on the request and response, which have relatively high readability. For example, requestBody defines the data needed for the request, required: true indicates that the request body is required, and content specifies the content type of the request body, which is application/json here. It should be noted that schema references a schema defined elsewhere in the document (CreateChatCompletionRequest) to describe the structure of the request body. The advantage of doing this is that the same schema can be referenced in multiple places, avoiding repeating the same content.

1 | requestBody: |

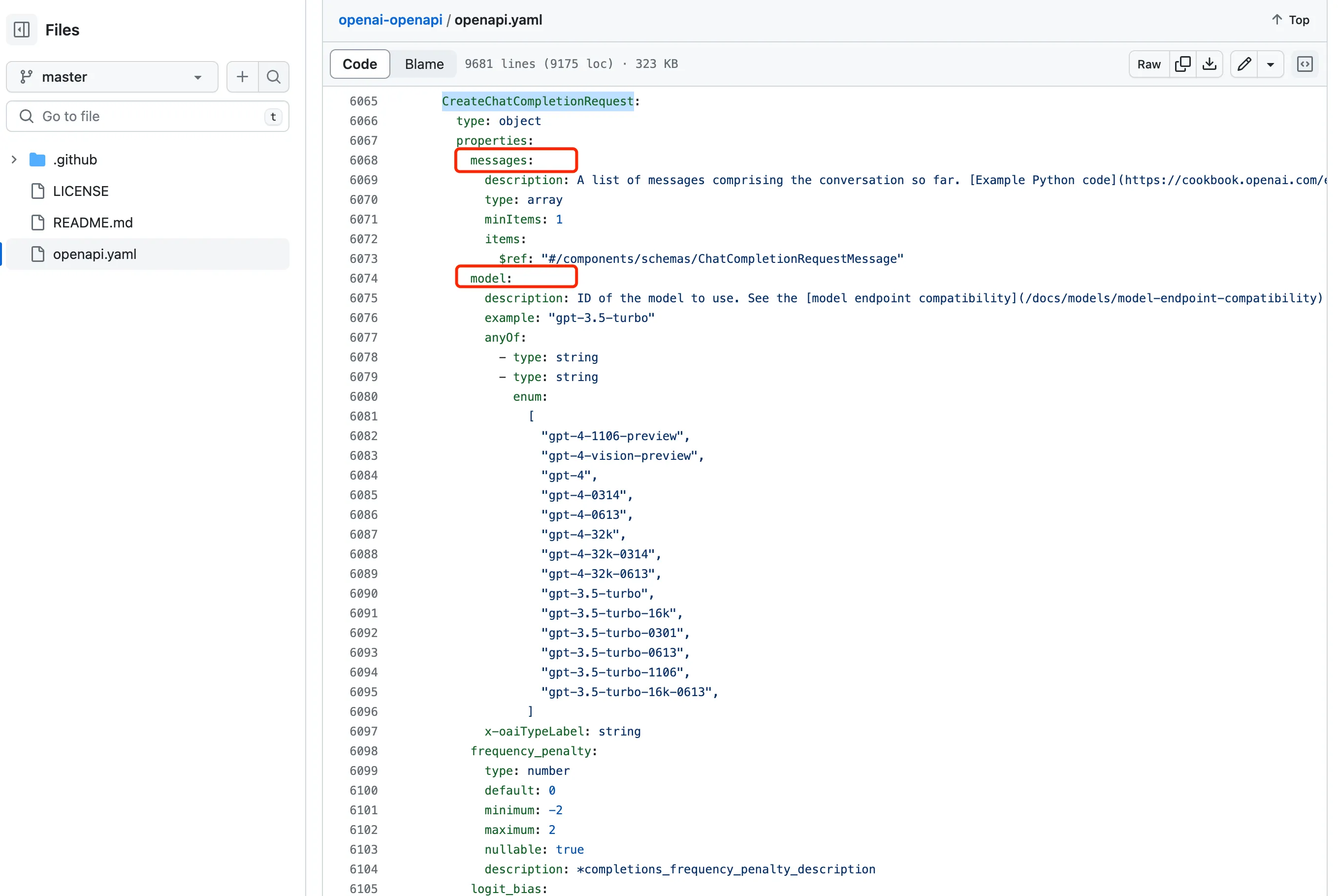

The definition of CreateChatCompletionRequest is later, as shown in the following image, which is also quite complex. It provides detailed descriptions of the type of each parameter in the request body, whether it’s required, whether it’s enum content, etc. The response to the request, responses, is similar, with the entire response package format specified by CreateChatCompletionResponse, which I won’t elaborate on here.

Definition of OpenAI's CreateChatCompletionRequest

Definition of OpenAI's CreateChatCompletionRequest

Next is the custom extended metadata x-oaiMeta section. name, group, returns, path provide additional information about the operation, and examples provide request and response examples for different scenarios, including code examples using cURL, Python, and Node.js, as well as corresponding response body examples. By providing specific usage examples, the API documentation becomes more understandable and usable.

Conclusion

Currently, stainless should still be in the beta stage, with only a few companies like OpenAI and Lithic using it, and there’s no detailed external documentation. Moreover, from the current pricing standards, it costs $250/month, which is a bit expensive for small developers. However, if it becomes mature enough in the future, it’s worth considering introducing stainless to generate code. This way, there’s no need for manual coding, and there’s less concern about code quality issues.

It has to be said that OpenAI is indeed a leader in AI. From this automated process of SDK code generation, we can also feel the continuous optimization of coding. As AI continues to mature, it’s believed that AI will participate more and more in coding, helping to generate more and more code.