Unexpected C++ String Modification Caused by COW (Copy-On-Write)

Recently, a colleague encountered a strange problem where in C++, after copying a string and modifying the copy’s content, the original value was also changed. For those not very familiar with C++, this seems a bit “spooky”. In this article, we’ll discuss this issue in depth, starting from a simple reproduction of the problem, to the underlying principles, and the changes in the C++ standard.

C++ string modification of copy affects original content

C++ string modification of copy affects original content

Problem Reproduction

Here’s a code snippet that can consistently reproduce the issue. We define a string ‘original’, make a copy of it, and then call a function to modify the content of the copy string. The function in the business code is more complex, but for reproduction, we use a simple function that only modifies the first character of the copy. We print the contents and memory addresses of both strings before and after modifying the copy. Before looking further, you can try to guess the output of the following code.

1 |

|

In the business production environment, compiling the above code with G++ 4.9.3 and running it produces the following result:

1 | Original: Hello, World!, address: 0x186c028 |

We can see that after modifying the copy, the content of the original string also changed. Another strange thing is that the memory addresses of the original string and the copy are always the same. What’s going on here? To answer this question, we need to first understand the implementation mechanism of C++ strings.

String Copy-On-Write

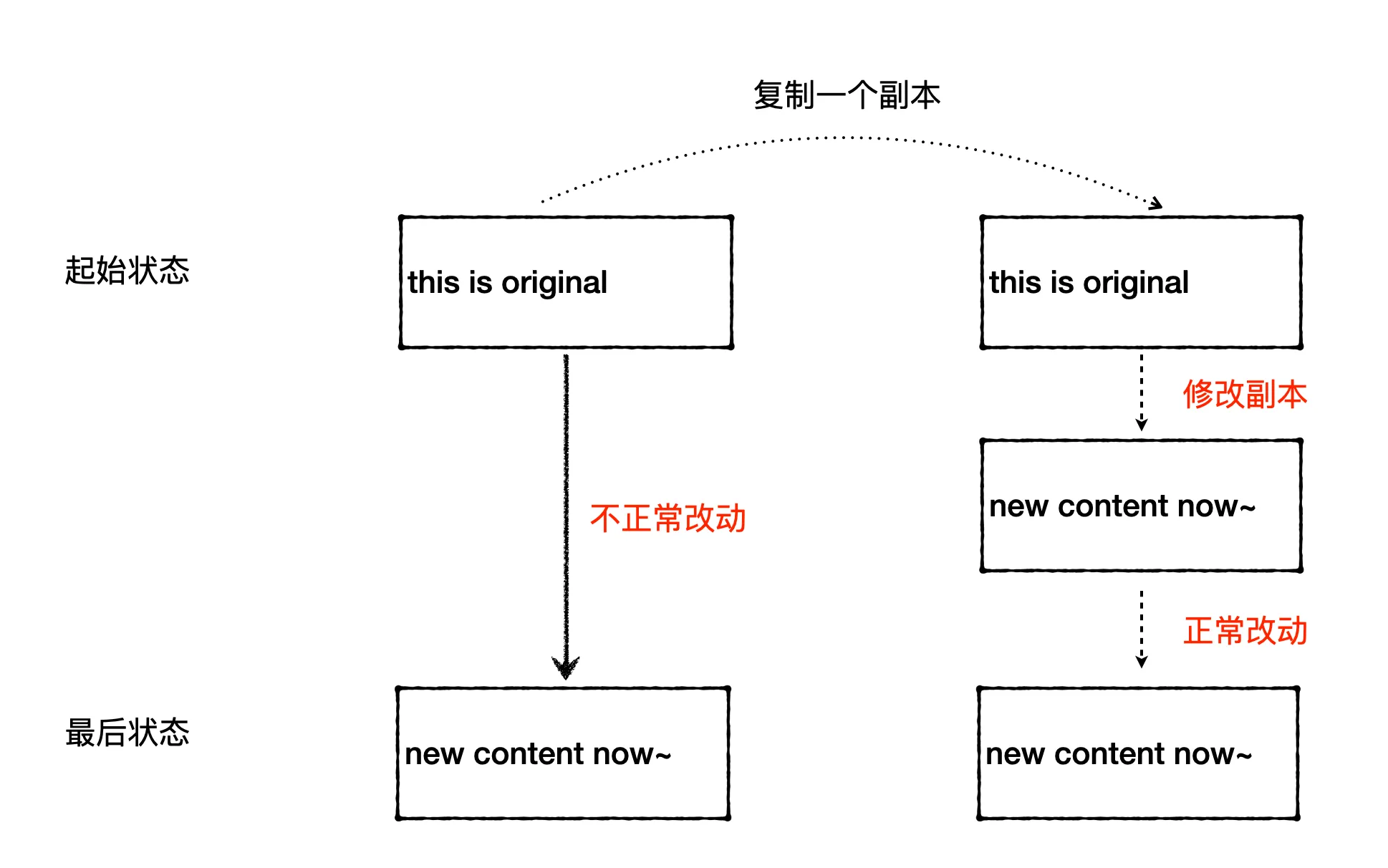

In lower versions of GCC/G++ (below version 5), the implementation of the string class adopts a Copy-On-Write (COW) mechanism. When a string object is copied, it doesn’t immediately copy the entire string data, but instead shares the same data with the original string. Only when a part of the string is modified (i.e., “written”) is a real copy of the data created. The advantage of COW is that it can significantly reduce unnecessary data copying, especially in scenarios where string objects are frequently copied but rarely modified.

The general implementation of COW:

- Reference Counting: A string object typically contains a pointer to the string data and a reference count. This reference count indicates how many string objects share the same data.

- Sharing on Copy: When a string object is copied, it simply copies the pointer to the data and the reference count, not the data itself. The copied string object shares the same data with the original object, and the reference count increases.

- Copying on Write: If any string object tries to modify the shared data, it first checks the reference count. If the reference count is greater than 1, it means the data is shared by multiple objects. In this case, the modification operation first creates a new copy of the data (i.e., “copy”), and then modifies this new copy. The reference count is then updated to reflect the change in sharing status.

COW implementation requires careful management of memory allocation and deallocation, as well as increasing and decreasing reference counts, to ensure data correctness and avoid memory leaks. Now, returning to the reproduction code above, we changed the copied string, but from the output results, it appears that the write copy in COW was not triggered, as the addresses are still the same before and after. Why is this? Let’s look at the implementation of ModifyStringInplace. The c_str() method of string returns a pointer to a constant character array, which by design is read-only and should not be used to modify the content of the string.

However, in the above implementation, const_cast was used to remove the const (constant) attribute of the object, and then the data in memory was modified. Direct modification of underlying data through a pointer will not be recognized by the string’s internal mechanism (including COW) because it bypasses the state check of the string’s externally exposed interface. If we slightly modify the above code to use [] to modify the content of the string, str[0] = 'X', it would trigger the write copy of COW, thus preventing the content of the original string from being modified. The output would be as follows:

1 | Original: Hello, World!, address: 0x607028 |

In fact, even just reading a character from the string using [] will trigger copy-on-write. For example, in the following code:

1 | { |

When compiled and run on a lower version of G++, we can see that after reading a character from the string using operator[], the address of the copy’s content also changes (from 0x21f2028 to 0x21f2058), as shown below:

1 | Original: Hello, World!, address: 0x21f2028 |

This is because operator[] returns a reference to the character, through which the content of the string can be modified. This interface has the semantics of “modifying” the string, so it triggers copy-on-write. Although the code above didn’t actually modify anything, the COW mechanism itself finds it difficult to perceive that no modification occurred here. Using iterators begin()/end() would have the same issue.

Drawbacks of Copy-On-Write

The advantage of implementing string with COW is that it can reduce unnecessary data copying, but it also has some drawbacks. Let’s look at a simple example, referring to an answer under Legality of COW std::string implementation in C++11.

1 | int main() { |

Under the COW mechanism, when copy is created as a copy of s, s and copy actually share the same underlying data. At this point, p points to the address of this shared data. Then, operator[] causes s to trigger a memory reallocation, and now only copy has a reference to the memory portion corresponding to p. When copy’s lifecycle ends and it is destroyed, p becomes a dangling pointer. Accessing the memory pointed to by a dangling pointer afterwards is undefined behavior, which may cause the program to crash or produce unpredictable output. If the COW mechanism were not used, this problem wouldn’t occur.

However, even in C++11 and later standards where std::string in the standard library no longer uses the COW mechanism, retaining pointers to internal string data is still an unsafe practice, because any operation that modifies the string may cause reallocation of the internal buffer, making previous pointers or references invalid.

Multi-threading Issues

Besides bringing the potential bugs mentioned above, COW has another significant flaw: it’s not suitable for multi-threaded environments. You can read the article Concurrency Modifications to Basic String for details. The problem brought by COW is:

The current definition of basic_string allows only very limited concurrent access to strings. Such limited concurrency will inhibit performance in multi-threaded applications.

Here’s a simple example. For the original string, several copies are made first, and then run in different threads. In a COW implementation, it must be ensured that operations on independent copy strings in each thread are thread-safe, which requires that the reference count of shared memory in the string must be an atomic operation. Atomic operations themselves have overhead, and in a multi-threaded environment, atomic operations on the same address by multiple CPUs have even greater overhead. If COW were not used in the implementation, this overhead could be avoided.

1 | // StringOperations modifies the string here |

Of course, if different threads share the same string object, then regardless of whether copy-on-write is used or not, thread synchronization is necessary here to ensure thread safety. We won’t discuss this further here.

C++11 Standard Improvements

Given the drawbacks of copy-on-write mentioned above, the GCC compiler, starting from version 5.1, no longer uses COW to implement string. You can refer to Dual ABI:

In the GCC 5.1 release libstdc++ introduced a new library ABI that includes new implementations of string and std::list. These changes were necessary to conform to the 2011 C++ standard which forbids Copy-On-Write strings and requires lists to keep track of their size.

This is mainly because the C++11 standard made changes. In 21.4.1 basic_string general requirements, there is such a description:

References, pointers, and iterators referring to the elements of a basic_string sequence may be invalidated by the following uses of that basic_string object:

- as an argument to any standard library function taking a reference to non-const basic_string as an argument.

- Calling non-const member functions, except operator[], at, front, back, begin, rbegin, end, and rend.

If the string is implemented with COW, as in the previous example, just calling non-const operator[] would also trigger copy-on-write, leading to invalidation of references to the original string.

String Optimization in Higher Versions

Higher versions of GCC, especially those following the C++11 standard and later versions, have made significant modifications to the implementation of std::string, mainly to improve performance and ensure thread safety. Higher versions of GCC abandoned COW and optimized for small strings (SSO). When a string is short enough to be stored directly in the internal buffer of the std::string object, it will use this internal buffer (on the stack) instead of allocating separate heap memory. This can reduce the overhead of memory allocation and improve performance when accessing small strings.

We can verify this with the following code:

1 |

|

Compiling and running with a higher version, you can see output similar to the following:

1 | 0x7ffcb9ff22d0:0x7ffcb9ff22e0 |

For shorter strings, the address is very close to the address of the variable itself, indicating it’s on the stack. For longer strings, the address is very different from the variable’s own address, indicating it’s allocated on the heap. For longer strings, higher versions of GCC have implemented more effective dynamic memory allocation and management strategies, including avoiding unnecessary memory reallocation and adopting incremental or doubling capacity strategies when growing strings, to reduce the number of memory allocations and improve memory utilization.