How an Async Thread Pool Exception Caused Service Chaos

0 CommentRecently, I encountered a very strange service restart issue in our business, and the troubleshooting process was quite complex. This article will review the process. The problem involves multiple aspects such as C++ thread pools, integer overflow, exception catching, and blocking, which is quite interesting.

Next, I will organize the content of this article according to the problem investigation process, starting with an introduction to the problem background, then listing the initial troubleshooting ideas and methods for locating abnormal requests. Then, through code analysis and some simple use cases to reproduce the problem, we will unveil the mystery of the service restart.

Problem Background

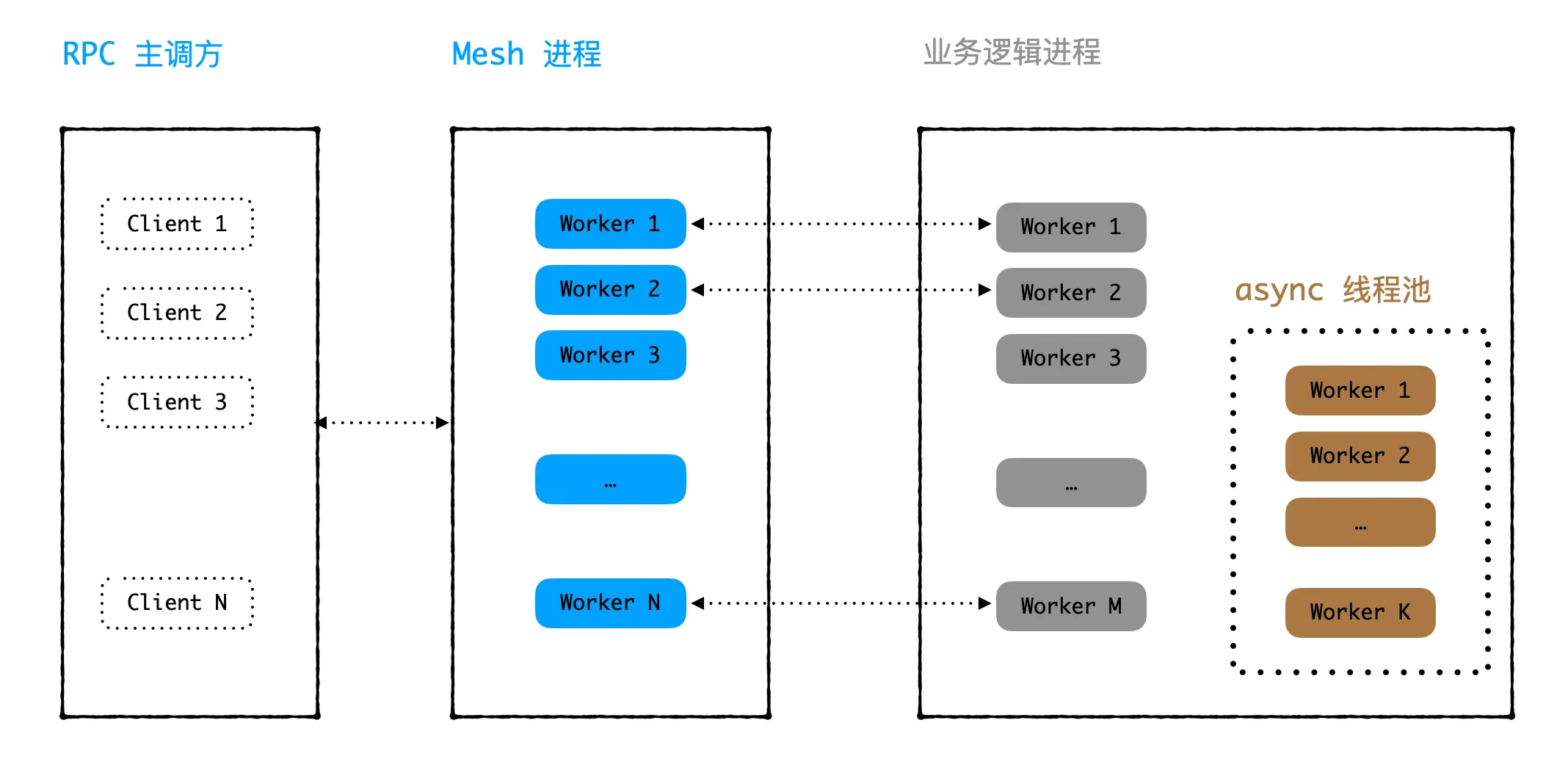

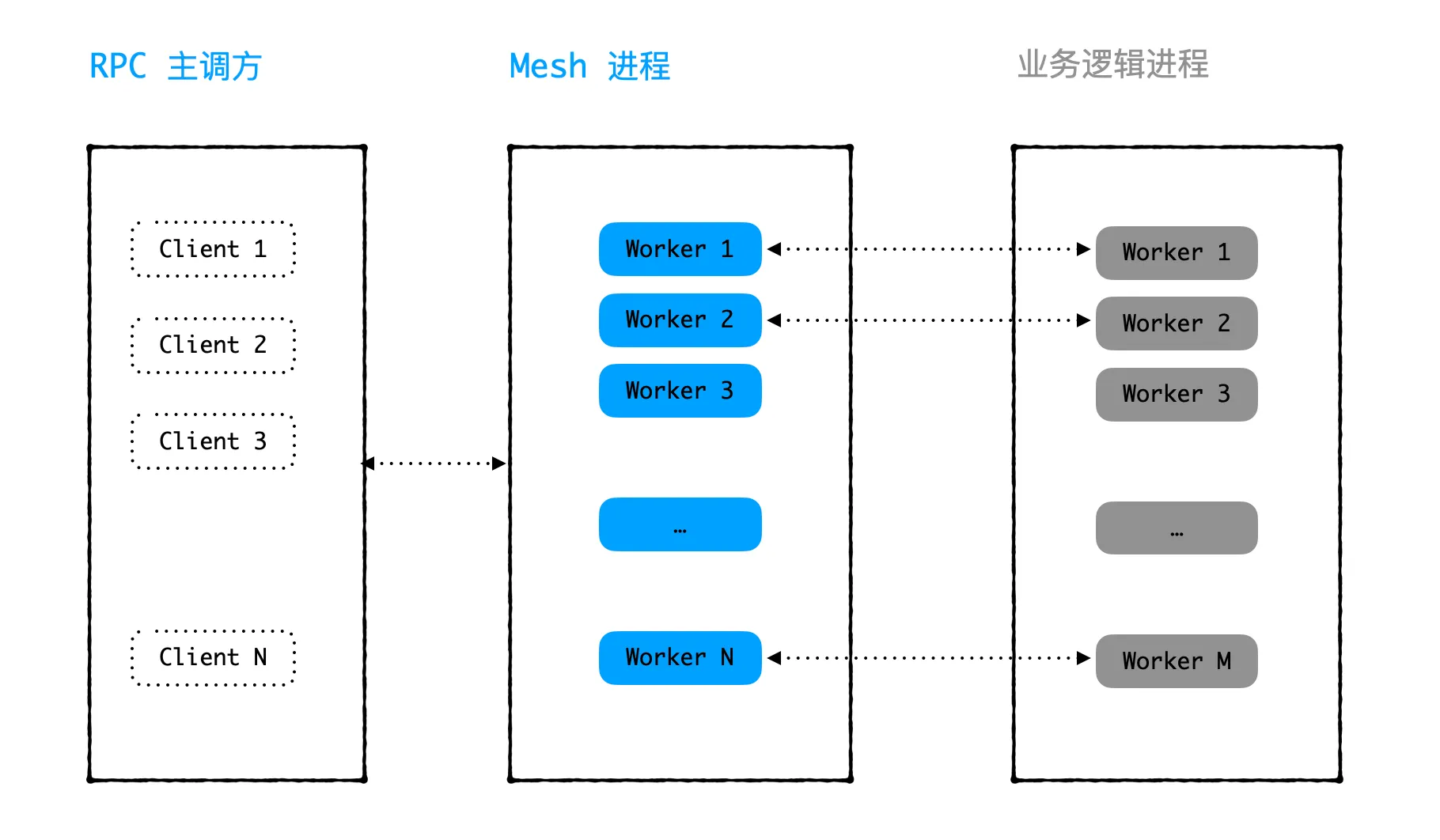

We have a module A that provides RPC services externally, and the main caller B calls A’s services. Module A’s service is divided into two processes: the mesh process and the business process, both of which are multi-threaded. The mesh process functions similarly to a Sidecar, assigning a worker thread to handle each RPC request received from the main caller. The worker sends the request package to the business process through a Unix socket and then waits for the business process to process it before replying to the main caller. The business process is specifically used for business logic, processing the request package and sending the response package to the worker in the mesh process. The overall process is shown in the following diagram:

Service divided into mesh process and business process

Service divided into mesh process and business process

Recently, the main caller B discovered through monitoring that there were several instances each day where it couldn’t connect to module A’s service port. Each instance didn’t last long and automatically recovered after a while.

A brief look at module A’s logs revealed that at the corresponding time points, the monitoring script failed to probe A’s service and thus restarted the service. The monitoring script here probes module A’s liveness detection RPC (which simply replies with a “hello”) at fixed intervals to check if the service is normal. If several consecutive probes fail, it considers the service to have a problem and attempts to restart it. This occasional restart of module A was due to the monitoring script being unable to get a reply from the liveness detection RPC, thus restarting the service.

So when did this problem start to occur? Extending the monitoring time for module A, we found that occasional mysterious restarts only started 7 days ago. Each server of module A experienced restarts, but the restart frequency was very low, so module A didn’t trigger any alarms.

Based on experience, probe failures are usually due to the service process crashing, such as the process exiting due to a coredump or being killed by the system due to an OOM (Out Of Memory) error. However, checking module A’s logs, we found it wasn’t either of these two situations. Module A didn’t show any coredump-related logs, and memory usage was normal during the restart periods. Could it be that there’s an infinite loop in the code causing the worker thread to be occupied and unable to release? Looking at the CPU usage during the restart periods, it was also at normal levels. Of course, if there’s a constant sleep in the infinite loop, the CPU usage wouldn’t be high, but there wasn’t anything using sleep in the business logic, so we initially ruled out an infinite loop.

This was a bit strange. Let’s continue to carefully examine the service logs for troubleshooting.

Initial Investigation

We found a machine that had recently restarted and first looked at the service process logs at the restart time point. The mesh process in module A is a C++ multi-threaded service with N worker threads concurrently processing business RPC requests. The framework prints logs at intervals, recording how many of the current workers are idle and how many are busy processing requests. Under normal circumstances, in the printed logs, most threads are idle, with only a few busy.

However, before the process restart, we found that the number of worker threads in the logs was a bit abnormal, with idle threads decreasing rapidly within 1 minute until reaching 0. Assuming a total of 200 workers, the relevant logs before the restart were roughly as follows:

1 | worker idle 100, busy 100; |

No wonder the monitoring script would fail to probe. At this moment, all of the service’s workers were occupied, with no idle workers to handle new incoming requests. All new requests would queue up waiting for a worker until timing out and failing.

So what caused the workers to be continuously occupied without being released? The service only recently started experiencing this issue, so we first thought it might be related to recent changes. We looked at the recent code changes but didn’t find any problems.

Next, there were actually two troubleshooting approaches. The first was to wait for the service process to get stuck again, then use gdb to attach to the process or use gcore to dump a coredump file. This would allow us to examine the call stack of the worker threads and see what function was causing the workers to be continuously occupied. We first ruled out gdb attach because the occurrence probability was quite low, and the monitoring script would restart the service in a very short time, making it difficult to find the right moment. Additionally, it’s not very suitable to attach to a production service for troubleshooting. As for gcore, it would require modifying the monitoring script to save the process coredump file when there’s a problem with the probe. However, considering that we needed to modify the monitoring script and that the coredump file might not necessarily reveal the problem, we didn’t adopt this approach for now.

The second approach was to find a request that could reproduce the problem and locate the issue through reproduction. After all, if a problem can be consistently reproduced, it’s as good as half solved. This is actually based on the assumption that intermittent problems are usually caused by certain special requests triggering some boundary conditions.

For our RPC module, if a special request causes a worker to be continuously occupied, then this request must be one that doesn’t receive a response. Therefore, we can print relevant logs when the module receives a request package and when it gives a response package. Then, during the time period when the service gets stuck, we can filter out those RPC requests in the logs that have requests but no responses.

After adding logs and deploying them, coincidentally, another service restart occurred. Through the logs, we finally found the suspicious request. Combined with this suspicious request, we discovered a problematic piece of code, which became the breakthrough point for solving the problem.

Problematic Code Analysis

Let’s first look at this problematic code. After simplification and hiding key information, it’s roughly as follows:

1 | int func() { |

As smart as you are, you must have noticed the problem with this code.

Here, i is an unsigned integer, and posVec.size() also returns an unsigned integer type size_t. When posVec.size() is less than gramCount, posVec.size() - gramCount will overflow, becoming a very large positive integer. Then in the loop, this very large positive integer will be used to traverse posVec, leading to array out of bounds. When using operator[] to access the array here, out-of-bounds access is undefined behavior, which generally causes the program to crash. I wrote a simple test code and found that it indeed resulted in a segmentation fault. It’s worth adding that if at is used to access the array, out-of-bounds access will throw an out_of_range exception, which will definitely crash if the exception is caught.

However, this code in module A didn’t crash, but instead caused the worker thread to be continuously occupied. Why is this? One suspicious point is that the above code is actually running in a newly opened thread pool. To add some background here, after module A receives an RPC request, it processes the business logic in a worker thread. Some business logic is quite time-consuming, so to improve processing speed, the time-consuming parts are put into an additional thread pool for concurrent execution.

The implementation of this thread pool is a bit complex, but the basic idea is a task queue + N pre-configured worker threads. The task queue is used to store tasks that need to be executed, and worker threads fetch tasks from the task queue to execute. The thread pool provides an interface RunTask(concur, max_seq, task); where concur is the number of threads for concurrent execution, max_seq is the total number of tasks, and task is the task function. RunTask will use concur threads to concurrently execute this task function task until all max_seq tasks are completed.

Before the task starts, RunTask defines a pipe to synchronize messages between the main thread and the task thread pool. Once all threads complete their tasks, the last exiting thread will write a character to the pipe to notify the main thread. The main thread will wait for the character in the pipe and then return.

The code with integer overflow above is placed in this additional thread pool for execution. Could the problem be caused by the thread pool? To quickly verify this hypothesis, I wrote a simple test script, putting the above code into the thread pool for execution, and the process indeed got stuck without response. The first guess was, could it be that the threads in the thread pool crashed due to array out of bounds, failed to write to the pipe, causing the main thread to block indefinitely on the pipe read operation?

Let’s verify this below.

Multithreading: thread

To verify the above hypothesis, I wrote a simple test program to simulate the workflow of the business thread pool. Here, C++11’s thread is used to start 5 new threads, and these threads sleep for a period of time to simulate task execution. When all threads have completed their tasks, the last completed thread writes a character to the pipe, and the main thread blocks on reading from the pipe. The test code is as follows:

1 |

|

After running, we found that this behaves as expected. 5 threads execute concurrently for 1s, and the main thread waits for the last thread to complete, then reads the result from the pipe and continues execution. The result is as follows:

1 | Main thread started Thread ID: 140358584862528 - 2024-06-12 11:40:51 |

Now, let’s make the last child thread directly throw an exception and see if the main thread blocks. We make the following changes based on the above code:

1 | //... |

After recompiling and running, we found that the entire process crashed directly. The result is as follows:

1 | Main thread started Thread ID: 140342189496128 - 2024-06-12 11:46:23 |

It seems the previous guess was wrong! In a multi-threaded environment, a single thread throwing an exception caused the entire process to abort. Why is this? We have to mention C++’s exception handling mechanism here.

C++ Exception Handling

In C++, when a program encounters a problem it can’t resolve on its own, it can throw an exception. Exceptions are usually objects derived from the standard exception class, such as std::runtime_error. When programming, you can put code that might throw exceptions inside a try block, followed by one or more catch blocks to catch and handle specific types of exceptions.

If an exception is not caught in the current scope, it will be propagated to higher levels of the try-catch structure in the call stack until a suitable catch block is found. If no suitable catch block is found throughout the entire call stack, std::terminate() will be called, with the specific execution operation specified by std::terminate_handler, which by default calls std::abort. If no signal handler is set to catch the SIGABRT signal, the program will be abnormally terminated.

For the example multi-threaded code above, the last thread throws an exception, but there’s nowhere to catch it, so std::abort() is ultimately called to terminate the entire process. From the output above, we can see that the last line is abort.

C++ is designed this way because an uncaught exception usually means the program has entered an unknown state, and continuing to run could lead to more serious errors, such as data corruption or security vulnerabilities. Therefore, immediately terminating the program is considered a safe failure mode.

Thread Object Lifecycle

There’s another point to mention here. In the example program above, the main thread calls thread.join() on each child thread’s thread object at the end. What happens if we comment this out and run the program? The process will still crash, and it’s also calling terminate(). Why is this?

Actually, the terminate documentation mentioned earlier states that terminate will be called in the following situation:

- A joinable std::thread is destroyed or assigned to.

Continuing to look at the std::thread::joinable documentation, we find the following explanation:

A thread that has finished executing code, but has not yet been joined is still considered an active thread of execution and is therefore joinable.

We know that child threads automatically exit after executing their related code. However, this doesn’t mean that the std::thread object associated with that thread will automatically handle all the resources and states of this thread. In C++, the ending of an operating system thread and the lifecycle management of a std::thread object are two related but relatively independent concepts:

- Operating system thread: When a thread finishes executing code, it automatically stops, and the thread’s system resources (such as thread descriptors and stack) are usually reclaimed by the operating system.

- std::thread object management: Although the thread has ended, the std::thread object still needs to correctly update its state to reflect that the thread is no longer active. This is mainly achieved through the join() or detach() methods. If these methods are not called, when the std::thread object is destroyed, it will detect that it still “owns” an active thread, which will lead to calling std::terminate().

In the example code above, when the main thread calls the join() method, it will block waiting for the child thread to finish executing (in this example, writing a character to the pipe has already ensured completion), and then mark the std::thread object state as “inactive”.

So, returning to the previous question, why does the main thread get stuck when a thread in the thread pool throws an exception in the business code? Upon closer inspection of the thread pool implementation code, we found that it doesn’t use thread to create threads, but uses std::async. What is async? How does it work, and could the thread getting stuck be related to async?

Let’s continue to verify together.

Multithreading: async

C++11 introduced std::async, which is a high-level tool for simplifying concurrent programming. It can run a function or callable object in an asynchronous execution context and return a std::future object to access the return value or exception state of that function.

Haha, after reading this introduction, are you confused and bewildered? Don’t worry, let’s set these aside and look at the code first. We’ll make some slight modifications based on the previous thread example code, using async for concurrent execution. The complete code is as follows:

1 |

|

After running, we found that the main thread got stuck!! The running result is as follows:

1 | Main thread started Thread ID: 140098007660352 - 2024-06-12 21:06:00 |

We have successfully reproduced the problem in the business. Before continuing with deeper analysis, let’s first look at how async is used, mainly as follows:

1 | int totalThreads = 5; |

The above code uses the std::async function to start a group of asynchronous tasks, defined by threadFunction. Each task is configured to execute on a new thread when created, and uses the std::launch::async strategy to ensure they start immediately. The execution results (or states) of these tasks are encapsulated in std::future

GDB Analysis

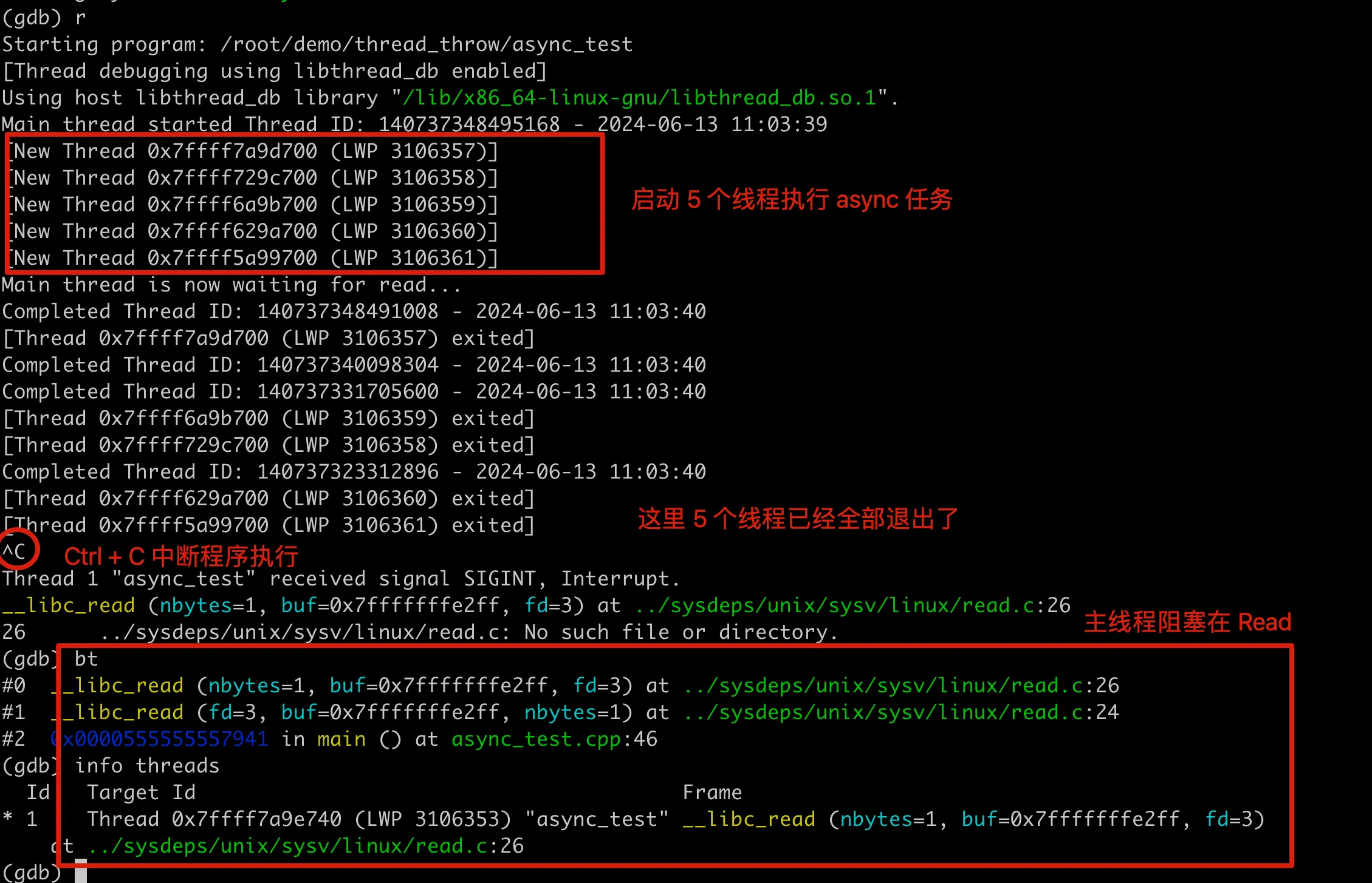

Let’s use GDB to see what happens during the process execution. After running here, we can see that 5 new threads are created to execute async tasks, then 4 threads print task output, and then all 5 threads are destroyed by the system. After that, the GDB console will get stuck. At this point, use Ctrl+C to pause program execution, and then you can use the GDB console.

GDB troubleshooting blocked process

GDB troubleshooting blocked process

After the process gets stuck, looking at the stack, we find it’s blocked on the read in the main function of the main thread. At this point, only the main thread remains in the process, which can be confirmed using info threads. Here, 0x7ffff7a9e740 is actually the hexadecimal of Thread ID: 140737348495168 printed at the beginning of the process. From the GDB results, we can see that the last child thread throws an exception before it’s about to write, then exits directly without writing a character to the pipe, and the main thread keeps blocking on the read of the pipe.

The question arises, shouldn’t the entire process abort and terminate? In the previous thread example, when the thread’s thrown exception wasn’t caught, it caused the process to abort, and the main thread also ended as a result. But here, the exception thrown by the thread created by async seems to have disappeared, with no place to catch it, and it didn’t trigger the process to abort. Why is this?

Async Exception Handling

Let’s first see if the async documentation says anything about how exceptions are handled.

If the function f returns a value or throws an exception, it is stored in the shared state accessible through the std::future that std::async returns to the caller.

We can see that if a thread started by std::async throws an exception, these exceptions will be caught and stored in the returned std::future object. Looking further at the future documentation, we find that future::get can be used to get the execution result of the task. If the task throws an exception, calling get will re-throw the exception.

If an exception was stored in the shared state referenced by the future (e.g. via a call to std::promise::set_exception()) then that exception will be thrown.

At this point, we’ve found the reason why the above example program didn’t abort, which lies in async’s exception handling mechanism. In async, exceptions thrown by threads are stored in std::future objects, rather than directly causing the process to abort. After the child thread throws an exception, it doesn’t write a character to the pipe, so the main thread keeps blocking on read waiting, causing the entire process to appear stuck.

Here, we can call get before read in the example program to catch the exception and print it out for verification.

1 | // ... |

We can see that an out_of_range exception is indeed caught here.

Advantages of Async

Regarding async, let’s add a bit more thought. What advantages does async introduced in C++11 have compared to traditional thread?

First, std::async provides a simpler way to create and execute asynchronous tasks compared to directly using std::thread. It automatically handles thread creation and management, allowing developers to focus on business logic rather than the details of thread management. std::async can automatically manage the lifecycle of tasks, including timely starting and terminating threads. Using std::async doesn’t require explicitly calling join() or detach().

Additionally, as mentioned earlier, tasks started using std::async can throw exceptions during execution, and these exceptions are caught and stored in the returned std::future object. By calling std::future::get(), these exceptions can be caught and handled in the main thread.

Furthermore, calling std::async allows specifying the launch mode (std::launch::async or std::launch::deferred), where std::launch::async forces the task to run immediately in a new thread, while std::launch::deferred delays the execution of the task until std::future::get() or std::future::wait() is called.

Generally speaking, when tasks need to be executed in parallel and have no dependencies on each other, using std::async without concerning about thread management will be much simpler. Or if you need to get the execution results of parallel tasks at some future point, combining std::async with std::future will also be much more convenient.

Production Service Review

Alright, now let’s return to the discussion of the production service. Through the previous analysis, we can now determine the source of the problem, but there are still a few details related to the production service that need to be clarified. The first is that the problematic code here had been online for a long time, so why did the problem only occur recently? Going back to the example in the Problematic Code Analysis section, if the array size is greater than or equal to gramCount, there would be no overflow and it wouldn’t cause a crash. Recently, the length of the array here changed, which is why the above problem occurred.

The second question is, each time abnormal data is encountered, it only blocks the current 1 working worker, and there shouldn’t be many abnormal request data in a short time. But when we observed the logs during the Initial Investigation, all workers were exhausted in an extremely short time. Why is this?

As mentioned in the Problem Background, both the mesh process and the business process are multi-threaded. The rapidly decreasing idle workers seen in the logs in a short time were from the mesh process. The actual business logic is handled in the business process, where all threads in the business process share a global thread pool implemented as an async singleton. The async-implemented thread pool specifies how many threads there are in total when creating the singleton object, and these threads are used by all business process worker threads. The overall structure is shown in the following diagram:

Whenever there is an abnormal data, it will cause 1 thread in the async thread pool to exit, while simultaneously blocking 1 thread in the business process. As time progresses, after accumulating enough abnormal data, two situations will occur:

All threads in the async thread pool exit due to exceptions. At this point, any business threads that haven’t been blocked will be blocked on read when using the thread pool to process data, regardless of whether the data is abnormal or not, because there are no async threads to compute. This situation occurs when the number of threads in the business process is greater than the number of threads in the async thread pool.

There are still working threads in the async thread pool, but all threads in the business process are blocked on read due to previously occurring abnormal data. This situation occurs when the number of threads in the business process is less than the number of threads in the async thread pool.

In either case, at some point, due to the last abnormal request data, all working threads in the business process will be blocked, unable to handle requests coming from mesh. From this moment on, every time mesh receives a request, one worker in the mesh process will be occupied. The accumulation of requests in a short time leads to all workers in the mesh process being occupied, and thus unable to handle new incoming requests, ultimately causing the monitoring script to detect service anomalies.

At this point, the reason for the restart has been revealed, and the fix method is also clear. The simplest method is to add a try-catch block when executing business functions in async threads. If an exception is caught, directly call abort to terminate the entire business process. This way, if there’s a bug in the code that causes an exception to be thrown, once triggered after going online, the process will immediately terminate. Problems will be discovered early, and it’s also convenient to analyze the problem from the coredump file.