LevelDB Explained - Preventing C++ Object Destruction

0 CommentIn the LevelDB source code, there’s a function for getting a Comparator that seemed a bit strange when I first saw it. It looks like it constructs a singleton, but it’s slightly more complex. The complete code is as follows:

1 | // util/comparator.cc |

Here, NoDestructor is a template class that, judging by its name, is used to prevent object destruction. Why prevent object destruction, and how is it achieved? This article will delve into these questions.

The NoDestructor Template Class

Let’s first look at the NoDestructor template class, which is used to wrap an instance so that its destructor is never called. This template class uses several advanced features, such as template programming, perfect forwarding, static assertions, alignment requirements, and placement new. Let’s explain each of these. First, here’s the complete code implementation:

1 | // util/no_destructor.h |

Let’s start with the constructor part. typename... ConstructorArgTypes indicates that this is a variadic template function, which can accept any number and type of parameters. This allows the NoDestructor class to be used with any type of InstanceType, regardless of how many parameters or what types of parameters its constructor needs. For more on variadic templates, you can also check out an article I wrote earlier: The Evolution of Variadic Arguments Implementation in C++.

The constructor parameter ConstructorArgTypes&&... constructor_args is a universal reference parameter pack, which, when used in conjunction with std::forward, can achieve perfect forwarding of parameters.

The constructor begins with two static assertions (static_assert) to check if instance_storage_ is large enough and meets the alignment requirements. The first static_assert ensures that the storage space allocated for InstanceType, instance_storage_, is at least as large as the InstanceType instance itself, to ensure there’s enough space to store an object of that type. The second static_assert ensures that the alignment of instance_storage_ meets the alignment requirements of InstanceType. The memory alignment requirements for objects are related to performance, which we won’t expand on here.

Then it starts constructing the object, using C++’s placement new syntax. &instance_storage_ provides an address, telling the compiler to construct the InstanceType object at this pre-allocated memory address. This avoids additional memory allocation, constructing the object directly in the reserved memory block. Next, using perfect forwarding, std::forward<ConstructorArgTypes>(constructor_args)... ensures that all constructor parameters are passed to InstanceType’s constructor with the correct type (preserving lvalue or rvalue properties). This is best practice for parameter passing in modern C++, reducing unnecessary copy or move operations and improving efficiency.

The memory address used for placement new construction earlier is provided by the member variable instance_storage_, whose type is defined by the std::aligned_storage template. This is a specially designed type used to provide a raw memory block that can safely store any type, while ensuring that the stored object type (InstanceType here) has appropriate size and alignment requirements. Here, the raw memory area created by std::aligned_storage is consistent with the memory area where the NoDestructor object is located, meaning that if NoDestructor is defined as a local variable within a function, both it and its instance_storage_ will be located on the stack. If NoDestructor is defined as a static or global variable, it and instance_storage_ will be in the static storage area, and objects in the static storage area have a lifetime that spans the entire program execution.

It’s worth noting that in the C++23 standard, std::aligned_storage will be deprecated. For more details, refer to Why is std::aligned_storage to be deprecated in C++23 and what to use instead?.

Returning to the example at the beginning of the article, the singleton object is a static local variable initialized the first time BytewiseComparator() is called, and its lifetime is as long as the entire program’s lifetime. When the program exits, the singleton object itself will be destructed and destroyed, but NoDestructor hasn’t added any logic in its destructor to destruct the object constructed in instance_storage_, so the BytewiseComparatorImpl object in instance_storage_ will never be destructed.

1 | const Comparator* BytewiseComparator() { |

LevelDB also provides a test case to verify that NoDestructor here behaves as expected.

Test Case

In util/no_destructor_test.cc, a struct DoNotDestruct is first defined, which calls std::abort() in its destructor. If the program runs or exits and calls the destructor of a DoNotDestruct object, the test program will terminate abnormally.

1 | struct DoNotDestruct { |

Then two test cases are defined, one defining a NoDestructor object on the stack, and the other defining a static NoDestructor object. These two test cases verify the behavior of NoDestructor objects on the stack and in the static storage area, respectively.

1 | TEST(NoDestructorTest, StackInstance) { |

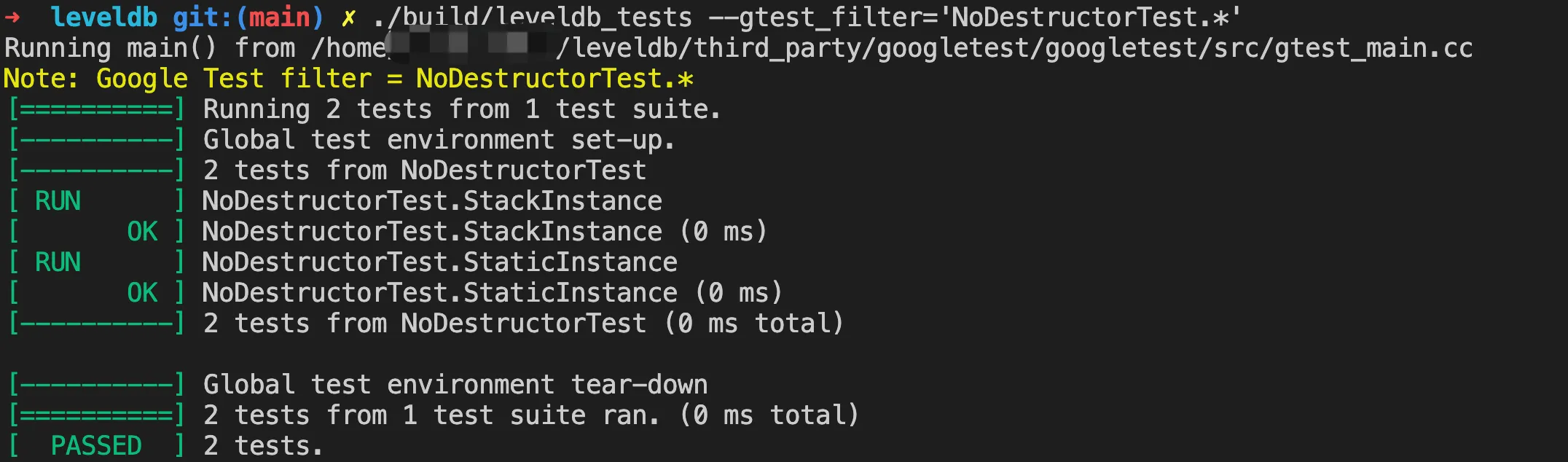

If the implementation of NoDestructor is problematic and cannot ensure that the destruction of the passed-in object is not executed, the test program will terminate abnormally. Let’s run these two test cases, and the result is as follows:

Test cases pass, destructor not called

Test cases pass, destructor not called

Here we can add a test case to verify what happens if we directly define a DoNotDestruct object, whether the test process will terminate abnormally. We can first define an object on the stack to test, placing it before the other two test cases, as follows:

1 | TEST(NoDestructorTest, Instance) { |

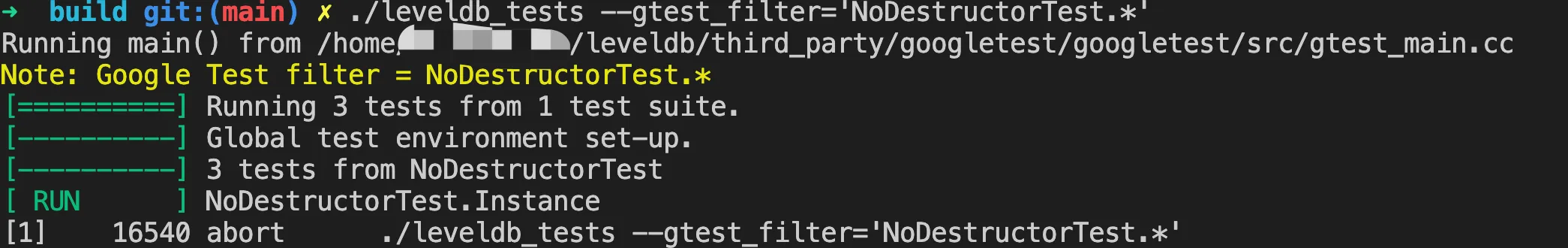

The result of running is as follows, this test case will terminate abnormally during execution, indicating that the destructor of the DoNotDestruct object was called.

Test process terminates abnormally, indicating destructor was called

Test process terminates abnormally, indicating destructor was called

Actually, we can modify this further by directly defining the instance object here with static, then compiling and re-running the test cases. You’ll find that all 3 test cases pass, but the test process still aborts at the end. This is because when the process exits, static objects are destructed, and at this time, the destructor of the DoNotDestruct object is called.

Why Can’t It Be Destructed?

In the above example, we saw the implementation of the NoDestructor template class, which serves to prevent the destruction of static local singleton objects. So why prevent object destruction? Simply put, the C++ standard does not specify the destruction order of static local variables in different compilation units. If there are dependencies between static variables and their destruction order is incorrect, it may lead to the program accessing already destructed objects, resulting in undefined behavior that could cause the program to crash.

Let’s take an example. Suppose there are two classes, one is a logging system and the other is some kind of service. The service needs to log information to the logging system during destruction. The code for the logger class is as follows:

1 | // logger.h |

Note the isAlive member variable of this class, which is initialized to true in the constructor and set to false in the destructor. In the log function, it first checks if isAlive is true, and if it’s false, it will trigger an assertion failure. Next is the code for the service class, which, as an example, only uses the static local variable of the logger class to record a log during destruction.

1 | // Service.h |

In the main function, use global variables globalService and globalLogger, where globalService is a global Service instance and globalLogger is a Logger singleton.

1 | // main.cpp |

Compile and run this program:

1 | g++ -g -fno-omit-frame-pointer -o main main.cpp |

After running, the assert assertion will most likely fail. We know that in a single compilation unit (here main.cpp), global variables are initialized in the order they appear, and then destructed in the reverse order. Here, globalLogger will be destructed first, then globalService. In globalService’s destructor, it will call Logger’s log function, but at this point globalLogger has already been destructed, isAlive has been set to false, so it will likely trigger an assertion failure. The reason we say “most likely” is because after the globalLogger object is destructed, the memory space it occupied may not yet have been reclaimed by the operating system or used for other purposes, so access to its member variable isAlive may still appear “normal”. Here’s the result of my run:

1 | Logger destroyed. |

In fact, if we don’t add the isAlive-related logic here, the output when running will most likely be as follows:

1 | Logger destroyed. |

From the output, we can see that, as before, globalLogger is destructed first, followed by globalService. However, the process is unlikely to crash here. This is because after globalLogger is destructed, although its lifecycle has ended, calls to member functions may still execute “normally”. The execution of member functions here usually depends on the class’s code (located in the code segment), and as long as the content of the code segment hasn’t been rewritten and the method doesn’t depend on member variables that have been destroyed or changed, it may still run without error.

Of course, even if it doesn’t trigger a program crash here, using an already destructed object is undefined behavior in C++. Undefined behavior means the program may crash, may run normally, or may produce unpredictable results. The results of such behavior may vary on different systems or at different runtimes, and we must avoid this situation in our development.

Actually, as far as LevelDB’s implementation here is concerned, BytewiseComparatorImpl is a trivially destructible object that doesn’t depend on other global variables, so its own destruction won’t be problematic. If we use it to generate a static local singleton object and then use it in other static local objects or global objects, these objects will call BytewiseComparatorImpl’s destructor when they are destructed. And according to the previous analysis, BytewiseComparatorImpl itself is a static local object, which may be destructed earlier than the objects using it when the process ends and resources are reclaimed. This would lead to repeated destruction, producing undefined behavior.

For more explanations about static variable destruction, you can also refer to the article Safe Static Initialization, No Destruction, where the author discusses this issue in detail.