LevelDB Explained - How to implement SkipList

4 CommentsIn LevelDB, the data in the memory MemTable is stored in a SkipList to support fast insertion. Skip lists are probabilistic data structures proposed by William Pugh in his paper Skip Lists: A Probabilistic Alternative to Balanced Trees. They are somewhat similar to ordered linked lists but can have multiple levels, trading space for time, allowing for fast query, insertion, and deletion operations with an average time complexity of . Compared to some balanced trees, the code implementation is relatively simple and performance is stable, making it widely applicable.

Inspirational approach to skip list implementation

Inspirational approach to skip list implementation

So, what are the principles behind skip lists? How are they implemented in LevelDB? What are the highlights and optimizations in LevelDB’s skip list implementation? How does it support single-threaded writing and concurrent reading of skip lists? This article will delve into these aspects from the principles and implementation of skip lists. Finally, it provides a visualization page that intuitively shows the construction and overall structure of skip lists.

Principles of Skip Lists

Skip lists are primarily used to store ordered data structures. Before delving into the principles of skip lists, let’s first look at how people stored ordered data before skip lists.

Storing Ordered Data

To store ordered abstract data types, the simplest method is to use ordered binary trees, such as binary search trees (BST). In a binary search tree, each node contains a key value that is comparable, allowing ordered operations. Any node’s left subtree contains only nodes with key values less than that node’s key value, while its right subtree contains only nodes with key values greater than that node’s key value.

Based on the structural definition of binary search trees, we can easily think of methods for insertion and search operations. For example, when searching, start from the root node of the tree and move down level by level. If the target key value is less than the current node’s key value, search the left subtree; if the target key value is greater than the current node’s key value, search the right subtree; if they are equal, the target node is found. Insertion is similar, finding the target and inserting at the appropriate position. The deletion operation is slightly more complex, requiring adjustment of the tree structure based on the current node’s subtree situation after finding the target node. We won’t expand on this here, but if you’re interested, you can learn more details in the binary search tree visualization blog.

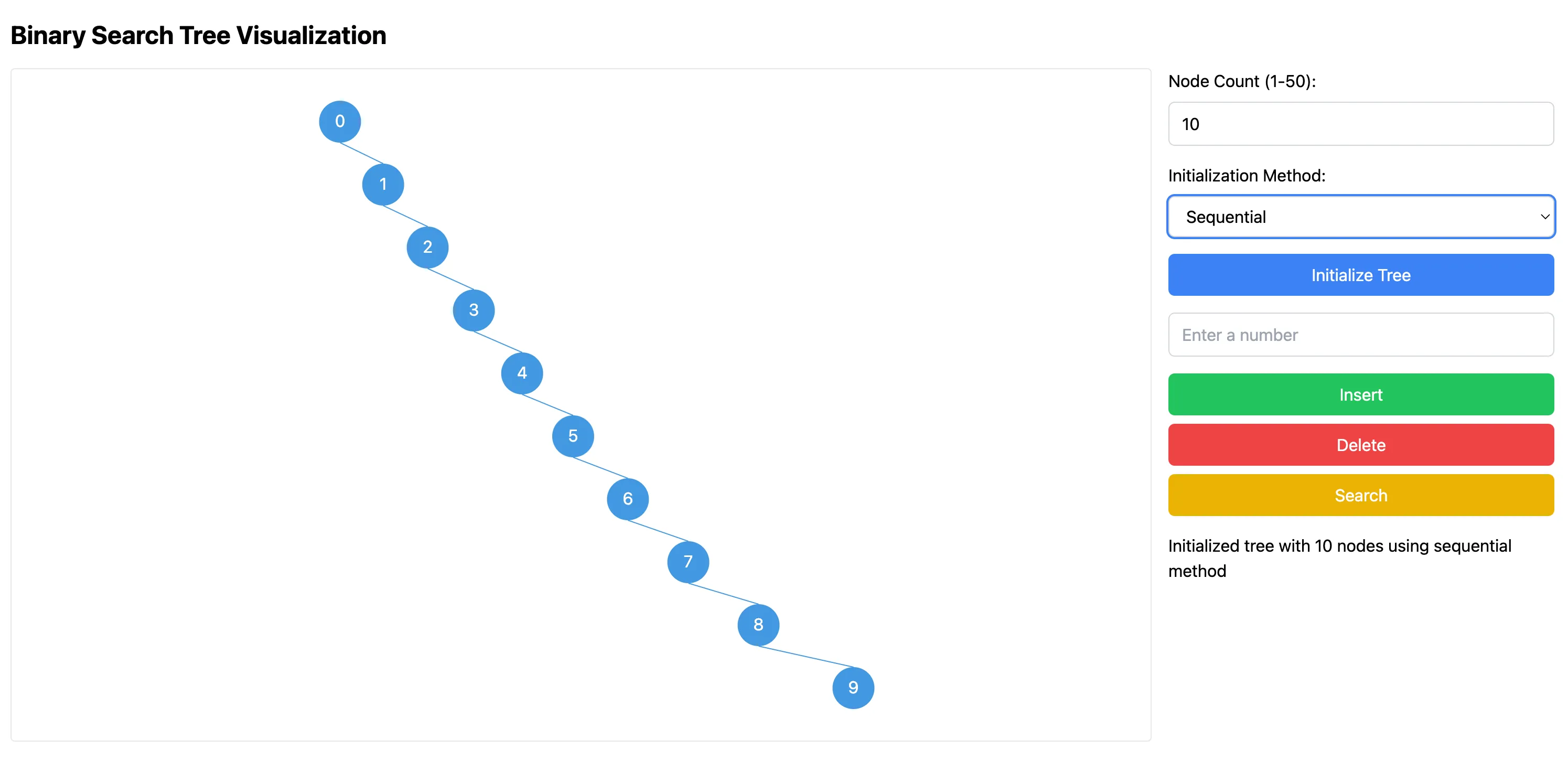

The average time complexity of binary search trees is , but if the elements in the binary search tree are inserted in order, the tree may degenerate into a linked list, causing the time complexity of operations to degrade from to . For example, the following figure shows the structure of a binary search tree after inserting 10 elements in order:

Binary search tree degenerating into a linked list

Binary search tree degenerating into a linked list

By the way, you can better understand binary search trees in this visualization page. To solve the performance degradation problem, people have proposed many balanced trees, such as AVL trees and red-black trees. The implementation of these balanced trees is relatively complex, adding some complicated operations to maintain the balance of the tree.

The Idea of Skip Lists

The balanced trees mentioned above all force the tree structure to satisfy certain balance conditions, thus requiring complex structural adjustments. The author of skip lists, however, took a different approach, introducing probabilistic balance rather than mandatory structural balance. Through a simple randomization process, skip lists achieve average search time, insertion time, and deletion time similar to balanced trees with lower complexity.

William Pugh didn’t mention in his paper how he came up with the idea of skip lists, only mentioning in the Related Work section that Sprugnoli proposed a randomized balanced search tree in 1981. Perhaps it was this randomized idea that inspired Pugh, eventually leading him to propose skip lists. In fact, the randomized idea is quite important. For example, Google’s Jumphash consistent hashing algorithm also uses probability to calculate which hash bucket should be used, which has several advantages compared to the hashring method.

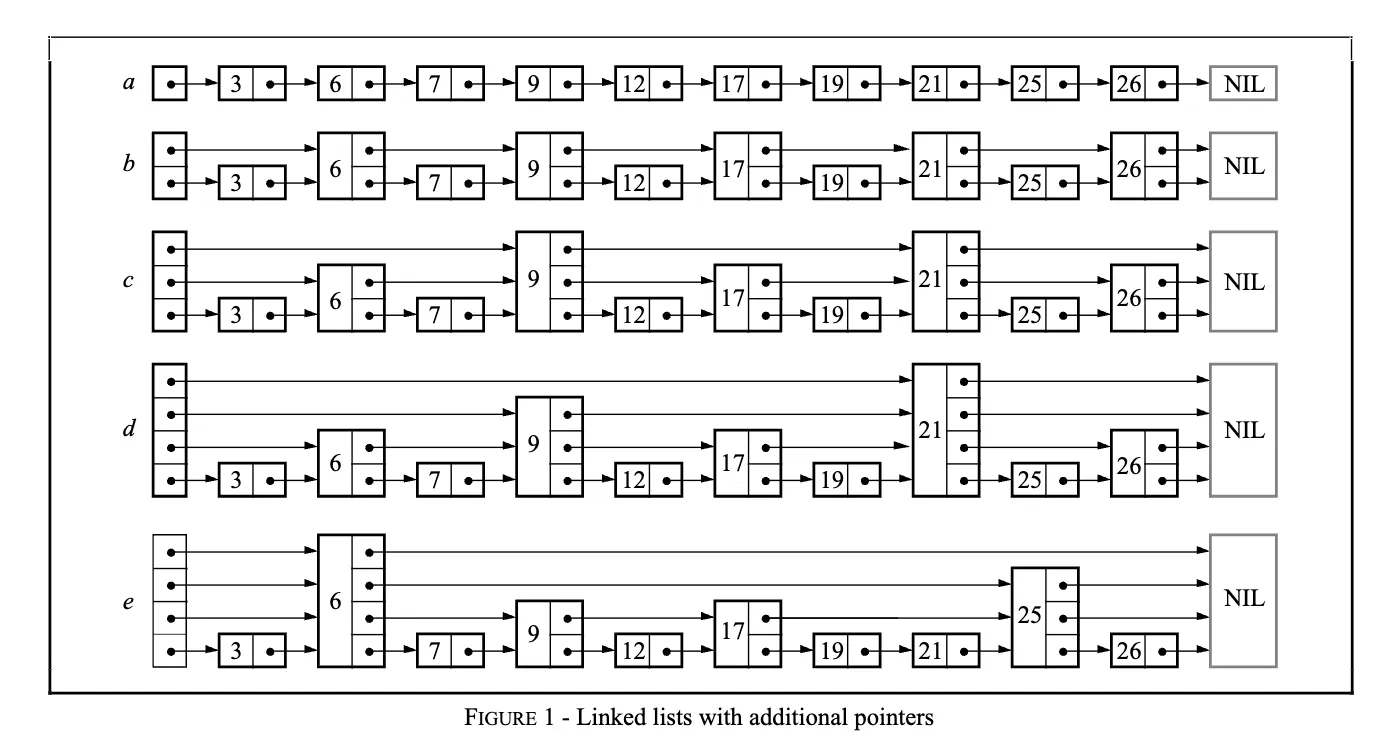

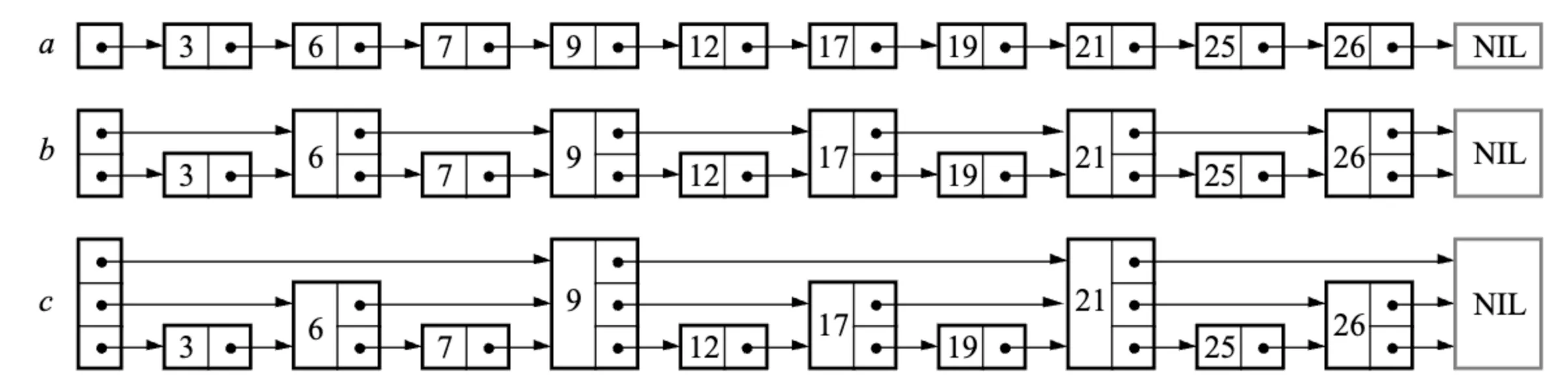

Before getting into the principles of skip lists, let’s review searching in ordered linked lists. If we want to search an ordered linked list, we can only scan from the beginning, resulting in a complexity of . However, this doesn’t take advantage of the ordered nature. If it were an ordered array, we could reduce the complexity to through binary search. The difference between ordered linked lists and ordered arrays is that we can’t quickly access middle elements through indices, only through pointer traversal.

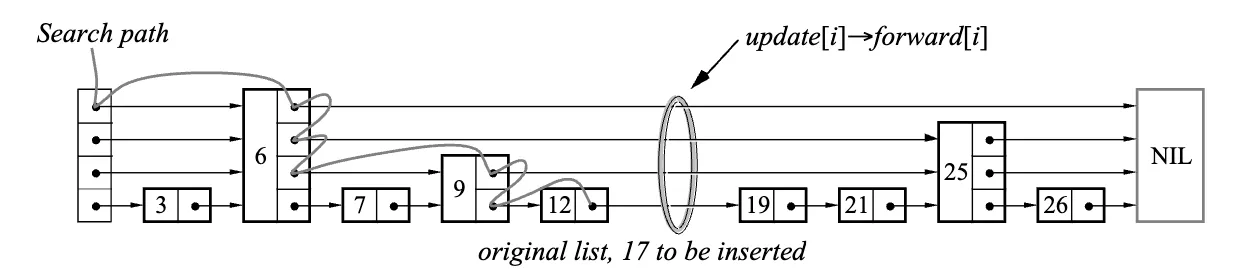

So, is there a way to skip some nodes during the search, thereby reducing search time? A fairly intuitive method is to create more pointers, trading space for time. Referring back to the figure at the beginning of the article, is the original ordered linked list, adds some pointer indexes, allowing jumps of 2 nodes at a time, and further adds pointer indexes, allowing jumps of 4 nodes at a time.

Trading space for time, adding node pointers to speed up search

Trading space for time, adding node pointers to speed up search

If the number of nodes at each level of pointers in the constructed linked list is 1/2 of the next level, then at the highest level, it only takes 1 jump to skip half of the nodes. In such a structure, searching is similar to an ordered array, where we can quickly locate the target node through binary search. Since the overall height of the linked list index is , the time complexity of searching is also .

It looks perfect, as long as we don’t consider insertion and deletion operations. If we need to insert or delete a new node, we need to disrupt and reconstruct the entire index layer, which is disastrous.

To solve this problem, the author of skip lists, Pugh, introduced the idea of randomization, using random decisions on node height to avoid the complex index layer reconstruction brought by insertion and deletion operations. At the same time, he mathematically proved that the implementation of skip lists would guarantee an average time complexity of .

The core idea of skip lists is actually similar to the multi-level index mentioned above, using multi-level indexes to accelerate searching. Each level is an ordered linked list, with the bottom level containing all elements. The nodes at each level are a subset of the nodes at the previous level, becoming sparser as we go up. The difference is that in skip lists, the height of levels is randomly decided, unlike the above where each level is 1/2 of the next level. Therefore, the cost of insertion and deletion operations is controllable, unlike the multi-level index which requires reconstructing the entire index layer.

Of course, there are still many details in the implementation of skip lists. Next, we’ll delve into this through the skip list implementation in LevelDB.

Implementation in LevelDB

The skip list implementation in LevelDB is in db/skiplist.h, mainly the SkipList class. Let’s first look at the design of this class.

SkipList Class

The SkipList class is defined as a template class. By using the template template <typename Key, class Comparator>, the SkipList class can be used for keys of any data type (Key), and the comparison logic for keys can be customized through an external comparator (Comparator). This SkipList only has a .h file, without a .cc file, because the implementation of template classes is usually in the header file.

1 | template <typename Key, class Comparator> |

The constructor of the SkipList class is used to create a new skip list object, where cmp is the comparator used to compare keys, and arena is the Arena object used to allocate memory. The SkipList class disables the copy constructor and assignment operator through delete, avoiding accidentally copying the entire skip list (which is unnecessary and costly).

The SkipList class exposes two core operation interfaces, Insert and Contains. Insert is used to insert new nodes, and Contains is used to check if a node exists. There is no operation provided here to delete nodes, because the data in MemTable in LevelDB is only appended, and data in the skip list will not be deleted. When deleting a key in the DB, it only adds a deletion type record in the MemTable.

1 | // Insert key into the list. |

To implement the skip list functionality, the SkipList class internally defines a Node class to represent nodes in the skip list. It is defined as an internal class because this can improve the encapsulation and maintainability of the skip list.

- Encapsulation: The Node class is a core part of the SkipList implementation, but users of SkipList usually don’t need to interact directly with node objects. Defining the Node class as a private internal class can hide implementation details;

- Maintainability: If the implementation of the skip list needs to be modified or extended, related changes will be confined to the internal of the SkipList class, without affecting external code using these structures, which helps with code maintenance and debugging.

The SkipList class also has some private members and methods to assist in implementing the Insert and Contains operations of the skip list. For example:

1 | bool KeyIsAfterNode(const Key& key, Node* n) const; |

In addition, to facilitate the caller to traverse the skip list, a public Iterator class is provided. It encapsulates common iterator operations such as Next, Prev, Seek, SeekToFirst, SeekToLast, etc.

Next, we’ll first look at the design of the Node class, then analyze how SkipList implements insertion and search operations. Finally, we’ll look at the implementation of the Iterator class provided externally.

Node Class

The Node class represents a single node in the skip list, including the node’s key value and multiple levels of successor node pointers. With this class, the SkipList class can construct the entire skip list. First, let’s give the code and comments for the Node class, you can take a moment to digest it.

1 | template <typename Key, class Comparator> |

First is the member variable key, whose type is the template Key, and the key is immutable (const). The other member variable next_ is at the end, using std::atomic<Node*> next_[1] to support dynamically expanding the size of the array. This is flexible array in C++, the next_ array is used to store all the successor nodes of the current node, next_[0] stores the next node pointer at the bottom level, next_[1] stores the one level up, and so on.

When creating a new Node object, additional memory will be dynamically allocated to store more next pointers based on the height of the node. SkipList encapsulates a NewNode method, the code is given in advance here so that you can better understand the creation of flexible array objects here.

1 | template <typename Key, class Comparator> |

The code here is less common, worth expanding on. First, calculate the memory size needed for Node, the size of Node itself plus the size of height minus 1 next pointers, then call Arena’s AllocateAligned method to allocate memory. Arena is LevelDB’s own memory allocation class, for detailed explanation, you can refer to LevelDB Explained - Arena, Random, CRC32, and More.. Finally, use placement new to construct Node object, this is mainly to construct Node object on the memory allocated by Arena, rather than constructing on the heap.

In addition, the Node class provides 4 methods, Next, SetNext, NoBarrier_Next and NoBarrier_SetNext, used to read and set the pointer to the next node. Here, the functionality is simply reading and setting the values of the next_ array, but it uses C++’s atomic types and some synchronization semantics, which will be discussed in the Concurrent Reading section later in this article.

That’s it for the Node class, next let’s look at how SkipList implements insertion and search operations.

Search Node

The most basic operation in a skip list is to find the node greater than or equal to a given key, which is the private method FindGreaterOrEqual in SkipList. The public Contains method, which checks if a certain key exists, is implemented through this. During node insertion, this method is also used to find the position to insert. Before looking at the specific implementation code in LevelDB, we can first understand the search process through a figure from the paper.

The search process starts from the highest current level of the skip list and proceeds to the right and down. To simplify some boundary checks in the implementation, a dummy node is usually added as the head node, not storing any specific value. When searching, first initialize the current node as the head node head_, then start searching from the highest level to the right. If the key of the node to the right on the same level is less than the target key, continue searching to the right; if it’s greater than or equal to the target key, search down to the next level. Repeat this search process until finding the node greater than or equal to the target key at the bottom level.

Now let’s look at the specific implementation code of FindGreaterOrEqual. The code is concise and the logic is clear.

1 | // Return the earliest node that comes at or after key. |

It’s worth mentioning the prev pointer array here, which is used to record the predecessor nodes at each level. This array is to support insertion operations. When inserting a node, we need to know the predecessor nodes of the new node at each level, so that we can correctly insert the new node. The prev array here is passed in as a parameter. If the caller doesn’t need to record the search path, they can pass in nullptr.

With this method, it’s easy to implement the Contains and Insert methods. The Contains method only needs to call FindGreaterOrEqual and then check if the returned node equals the target key. Here, we don’t need predecessor nodes, so we can pass nullptr for prev.

1 | template <typename Key, class Comparator> |

Insert Node

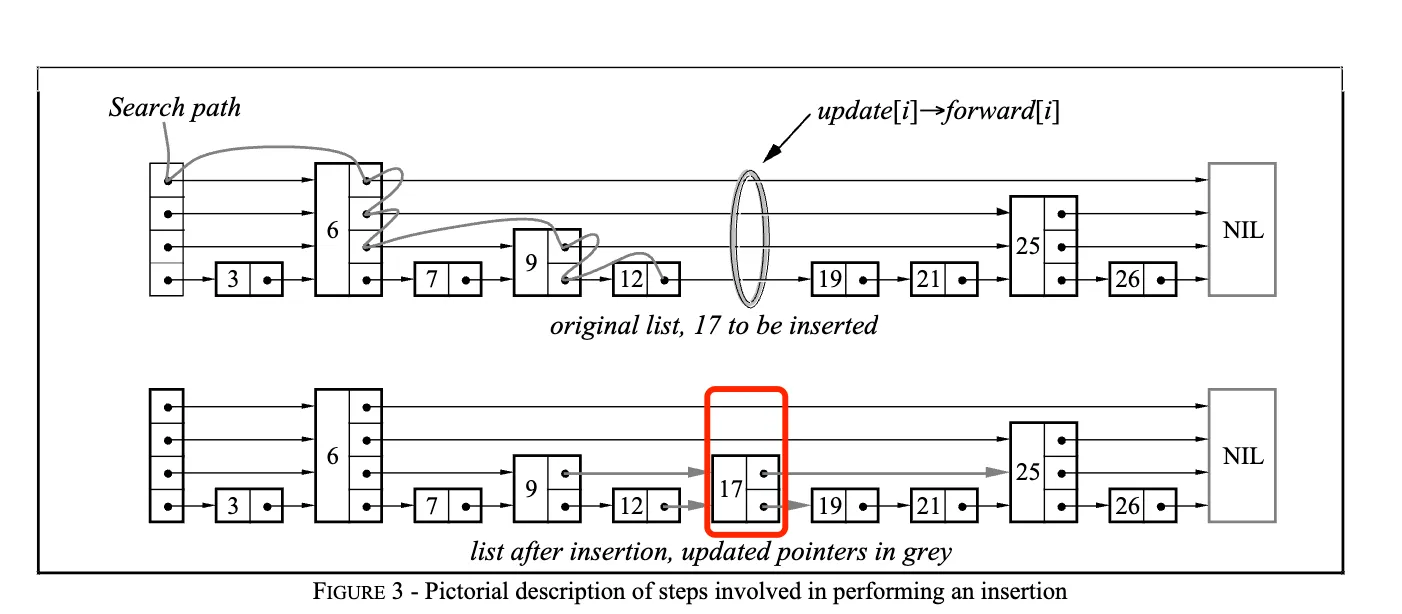

Inserting a node is relatively more complex. Before looking at the code, let’s look at the figure given in the paper. The upper part is the logic of finding the position to insert, and the lower part is the skip list after inserting the node. Here we can see that a new node has been added, and the pointers pointing to the new node and the pointers from the new node to the subsequent nodes have been updated.

Skip list node insertion process

Skip list node insertion process

So what is the height of the newly inserted node? How are the pointers of the preceding and following nodes updated after insertion at the corresponding position? Let’s look at the implementation code in LevelDB.

1 | template <typename Key, class Comparator> |

The code above omits some comments and is divided into 3 functional blocks. Here’s an explanation for each part:

- First, define an array prev of type

Node*with a length ofkMaxHeight=12, which is the maximum supported level height of the skip list. This array stores the predecessor nodes of the new node to be inserted at each level. When inserting a new node in the skip list, we can find the position to insert the new node at each level through this prev array. - Use a random algorithm to decide the level height of the new node. Here, LevelDB starts with an initial height of 1, then decides whether to increase a level with a 1/4 probability. If the height of the new node exceeds the current maximum height of the skip list, we need to update the maximum height and set the prev for the exceeding parts to the head node, because the new levels start from the head node.

- Create a new node with a height of height and insert it into the linked list. The specific method is also simple: iterate through each level of the new node, use the NoBarrier_SetNext method to set the next node of the new node, then update the next node of the prev node to the new node, achieving the insertion of the new node. NoBarrier_SetNext indicates that in this context, no additional memory barriers are needed to ensure the visibility of memory operations. The insertion of the new node is not much different from the insertion operation of a general linked list. There’s a good visualization here that can deepen your understanding of linked list insertion.

Now let’s look at some of the details. First, let’s look at the RandomHeight method, which is used to generate the height of new nodes. The core code is as follows:

1 | template <typename Key, class Comparator> |

Here, rnd_ is a Random object, which is LevelDB’s own linear congruential random number generator class. For a detailed explanation, you can refer to LevelDB Explained - Arena, Random, CRC32, and More.. In the RandomHeight method, each loop has a 1/4 probability of increasing a level, until the height reaches the maximum supported height kMaxHeight=12 or doesn’t meet the 1/4 probability. The total height of 12 and the probability value of 1/4 are empirical values, which are also mentioned in the paper. We’ll discuss the choice of these two values in the performance analysis section later.

The insertion into the linked list actually needs to consider concurrent reading issues, but we won’t expand on that here. We’ll discuss it specifically later. Next, let’s look at the design of the Iterator class in SkipList.

Iterator Design

The Iterator class is mainly used for traversing nodes in the skip list. The design and usage of iterators here are quite interesting. LevelDB defines an abstract base class leveldb::Iterator in include/leveldb/iterator.h, which contains general iterator interfaces that can be used for different data structures.

On the other hand, SkipList<Key, Comparator>::Iterator is an internal class of SkipList, defined in db/skiplist.h, which can only be used for the SkipList data structure. The Iterator of the skip list does not inherit from the leveldb::Iterator abstract base class, but is used in combination as a member of the MemTableIterator object. Specifically, it’s used in db/memtable.cc, where the MemTableIterator class is defined, inheriting from Iterator, and then rewriting its methods using the Iterator of the skip list.

1 | class MemTableIterator : public Iterator { |

Here, MemTableIterator acts as an adapter, adapting the functionality of SkipList::Iterator to a form that conforms to LevelDB’s external Iterator interface, ensuring the consistency of interfaces between various parts of LevelDB. If there’s a need to replace the skip list implementation or iterator behavior in memtable in the future, MemTableIterator can be modified locally without affecting other code using the Iterator interface.

So how is the SkipList::Iterator class specifically defined? As follows:

1 | // Iteration over the contents of a skip list |

By passing in a SkipList pointer object, you can traverse the skip list. The class defines a Node* node_ member variable to record the currently traversed node. Most methods are not difficult to implement, just needing to encapsulate the methods in the skip list introduced earlier. There are two special methods that require adding new methods to the skip list:

1 | template <typename Key, class Comparator> |

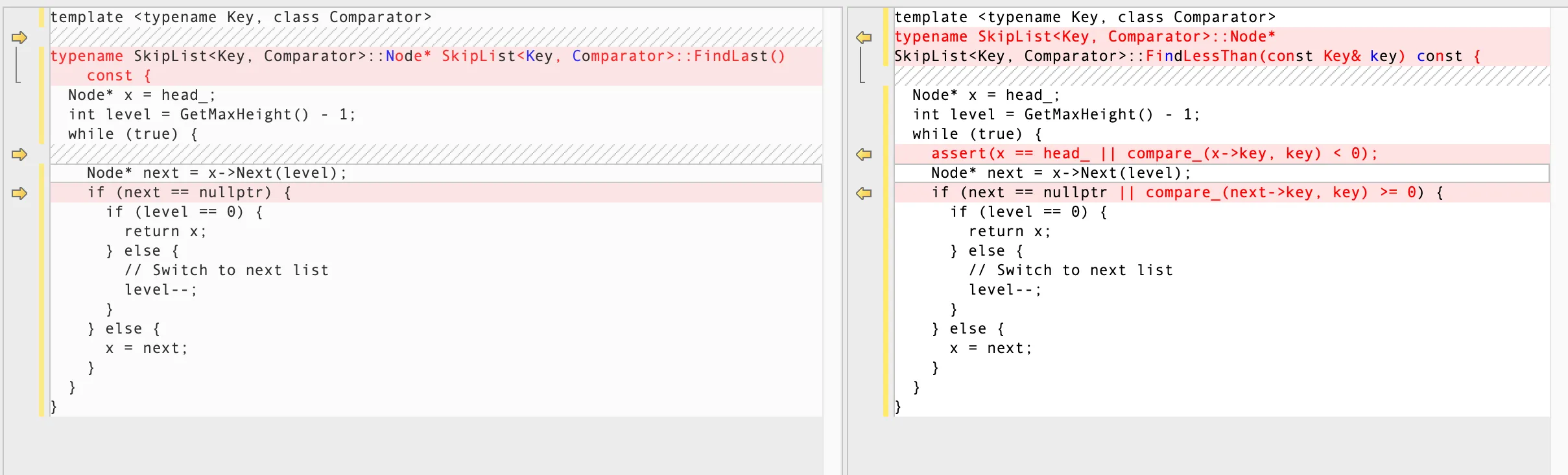

These call the skip list’s FindLessThan and FindLast methods respectively to implement the Prev and SeekToLast methods. FindLessThan searches for the largest node less than the given key, while FindLast searches for the last node in the skip list (i.e., the largest node). These two methods are very similar to each other and also very similar to the FindGreaterOrEqual method. The following figure lists the differences between these two methods.

Differences between FindLessThan and FindLast methods in skip list

Differences between FindLessThan and FindLast methods in skip list

The basic idea is to start from the head node of the skip list and search right and down level by level. At each level, check if the next node of the current node exists. If the next node doesn’t exist, switch to the next level and continue searching. If it exists, we need to judge whether to search right based on the situation. Finally, they all reach the bottom level (level 0) and return a certain node.

At this point, the core functionality implementation of the skip list has been fully clarified. However, there’s still one question that needs to be answered: are the operations of this skip list thread-safe in a multi-threaded situation? When analyzing the implementation of the skip list above, we intentionally ignored multi-threading issues. Let’s look at this in detail next.

Concurrent Read

We know that although LevelDB only supports single-process use, it supports multi-threading. More accurately, when inserting into memtable, LevelDB uses locks to ensure that only one thread can execute the Insert operation of the skip list at the same time. However, it allows multiple threads to concurrently read data from the SkipList, which involves multi-threaded concurrent reading issues. How does LevelDB support single write and multiple reads here?

During the Insert operation, there are two pieces of data being modified: one is the current maximum height max_height_ of the entire linked list, and the other is the node pointer update caused by inserting a new node. Although the writing process is single-threaded, the updates to the maximum height and next pointers are not atomic, and concurrent reading threads may read old height values or unupdated next pointers. Let’s see how LevelDB solves this problem.

When inserting a new node, first read the current maximum height of the linked list. If the new node is higher, the maximum height needs to be updated. The current maximum height of the linked list is recorded using the atomic type std::atomic

1 | inline int GetMaxHeight() const { |

For reading threads, if they read a new height value and updated node pointers, there’s no problem, as the reading threads correctly perceive the new node. But if the writing thread hasn’t finished updating the node pointers, and the reading thread reads the new height value, it will start searching from the new height. At this time, head_->next[max_height_] points to nullptr, so it will continue searching downwards, which won’t affect the search process. In fact, in this situation, if the writing thread has updated the pointers at lower levels, the reading thread may also perceive the existence of the new node.

Also, could it happen that the writing thread updates the new node pointers, but the reading thread reads the old height? We know that compilers and processors may reorder instructions, as long as this reordering doesn’t violate the execution logic of a single thread. In the above write operation, max_height_ might be written after the node pointers are updated. At this time, if a reading thread reads the old height value, it hasn’t perceived the newly added higher levels, but the search operation can still be completed within the existing levels. In fact, for the reading thread, it perceives that a new node with a lower level has been added.

Memory Barriers

Actually, we’ve overlooked an important point in the previous analysis, which is the concurrent reading problem when updating level pointers. Earlier, we assumed that when updating the new node’s level pointers, the writing thread updates level by level from bottom to top, and reading threads might read partial lower level pointers, but won’t read incomplete level pointers. To efficiently implement this, LevelDB uses memory barriers, which starts from the design of the Node class.

In the Node class implementation above, the next_ array uses the atomic type, which is the atomic operation type introduced in C++11. The Node class also provides two sets of methods to access and update pointers in the next_ array. The Next and SetNext methods are with memory barriers, and the main functions of memory barriers are:

- Prevent reordering: Ensure that all write operations before the memory barrier are completed before operations after the memory barrier.

- Visibility guarantee: Ensure that all write operations before the memory barrier are visible to other threads.

Specifically here, the SetNext method uses the atomic store operation and specifies the memory order memory_order_release, which provides the following guarantee: all write operations before this store will be completed before this store, and all read operations after this store will start after this store. The Next method used by reading threads uses memory_order_acquire to read the pointer, ensuring that read or write operations occurring after the read operation are not reordered before the load operation.

The NoBarrier_Next and NoBarrier_SetNext methods are without memory barriers. These two methods use memory_order_relaxed, and the compiler won’t insert any synchronization or barriers between this operation and other memory operations, so it doesn’t provide any memory order guarantee, which will have higher performance.

That’s enough background for now. It’s a bit complicated, but don’t worry, let’s look at it in conjunction with the code:

1 | x = NewNode(key, height); |

This code updates the new node’s level pointers from bottom to top. For the i-th level, as long as the writing thread completes SetNext(i, x), modifying the pointer pointing to the new node x at this level, other reading threads can see the fully initialized i-th level. Here we need to understand the meaning of full initialization. We can assume there are no memory barriers here, what situation would occur?

- Inconsistent multi-level pointers: Pointers at different levels might be updated in an inconsistent order, and reading threads might see that high-level pointers have been updated, but low-level pointers haven’t been updated yet.

- Memory visibility issues: In multi-core systems, write operations on one core may not be immediately visible to other cores, causing other threads to possibly not see the newly inserted node for a long time.

- Node pointer disorder: Here, the pointer pointing to the new node is updated first, but the successor pointer of the new node hasn’t been updated. This causes reading threads to read the new node but find no successor pointer, thinking they’ve reached the end.

With memory barriers, it ensures that from bottom to top, each level is in a fully initialized state. LevelDB has also optimized to the extreme here, reducing unnecessary memory barriers. When inserting node x at level i, both the successor and predecessor pointers of x need to be updated. For the successor pointer, using the NoBarrier_SetNext method is sufficient because a memory barrier will be added when setting the predecessor pointer later. The comment in the code also mentions this point.

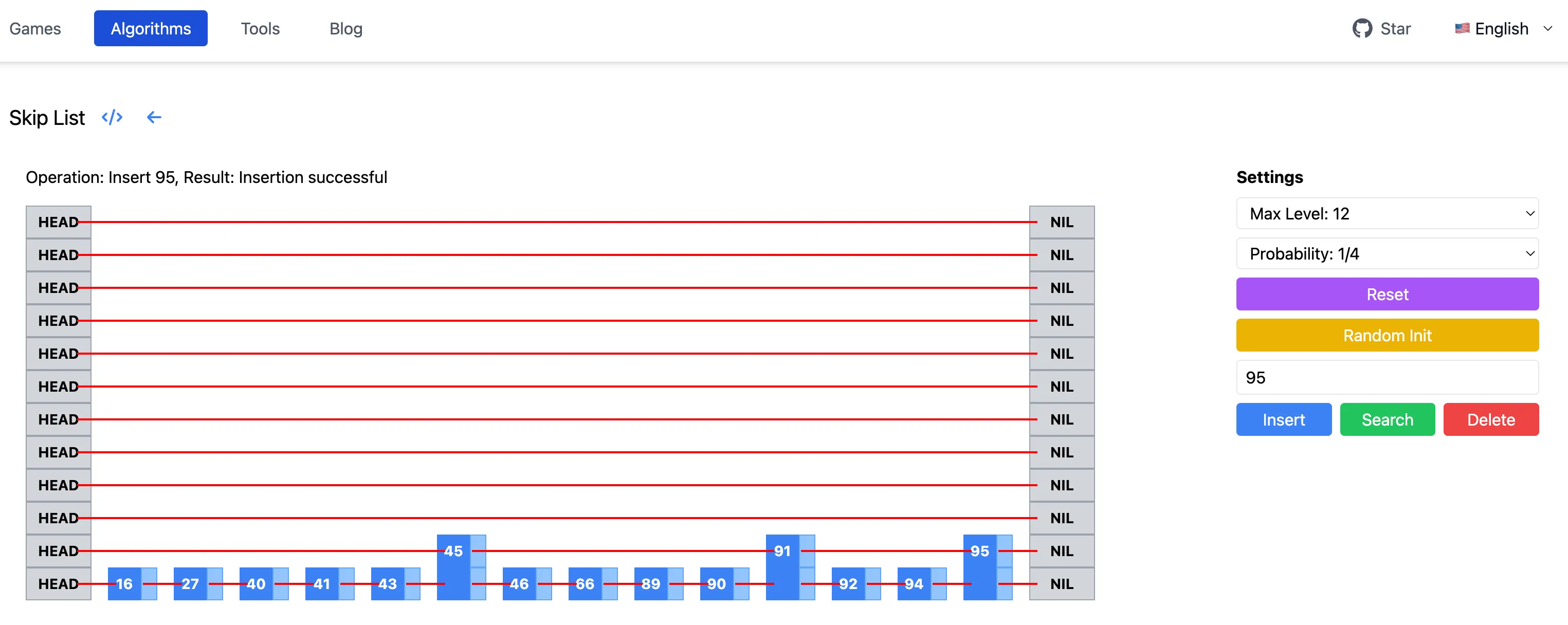

Online Visualization

To intuitively see the process of building a skip list, I used Claude3.5 to create a skip list visualization page. You can specify the maximum level height of the skip list, adjust the probability of increasing level height, then randomly initialize the skip list, or insert, delete, and search for nodes, observing the changes in the skip list structure.

Online visualization of skip lists

Online visualization of skip lists

With a maximum of 12 levels and an increasing probability of 1/4, you can see that the average level height of the skip list is quite low. You can also adjust the probability to 1/2 here to see the changes in the skip list.

Summary

Skip lists are probabilistic data structures that can be used to replace balanced trees, implementing fast insertion, deletion, and search operations. The skip list implementation in LevelDB has concise code, stable performance, and is suitable for storing data in memory MemTables. This article has deeply discussed the principles and implementation of skip lists, and finally provided a visualization page where you can intuitively see the construction process of skip lists.

One of the great advantages of LevelDB is that it provides detailed tests. So how is the skip list tested here? Additionally, by introducing randomization, skip lists perform similarly to balanced trees. How can we analyze the performance of skip lists? See you in the next article~