LevelDB Explained - Static Thread Safety Analysis with Clang

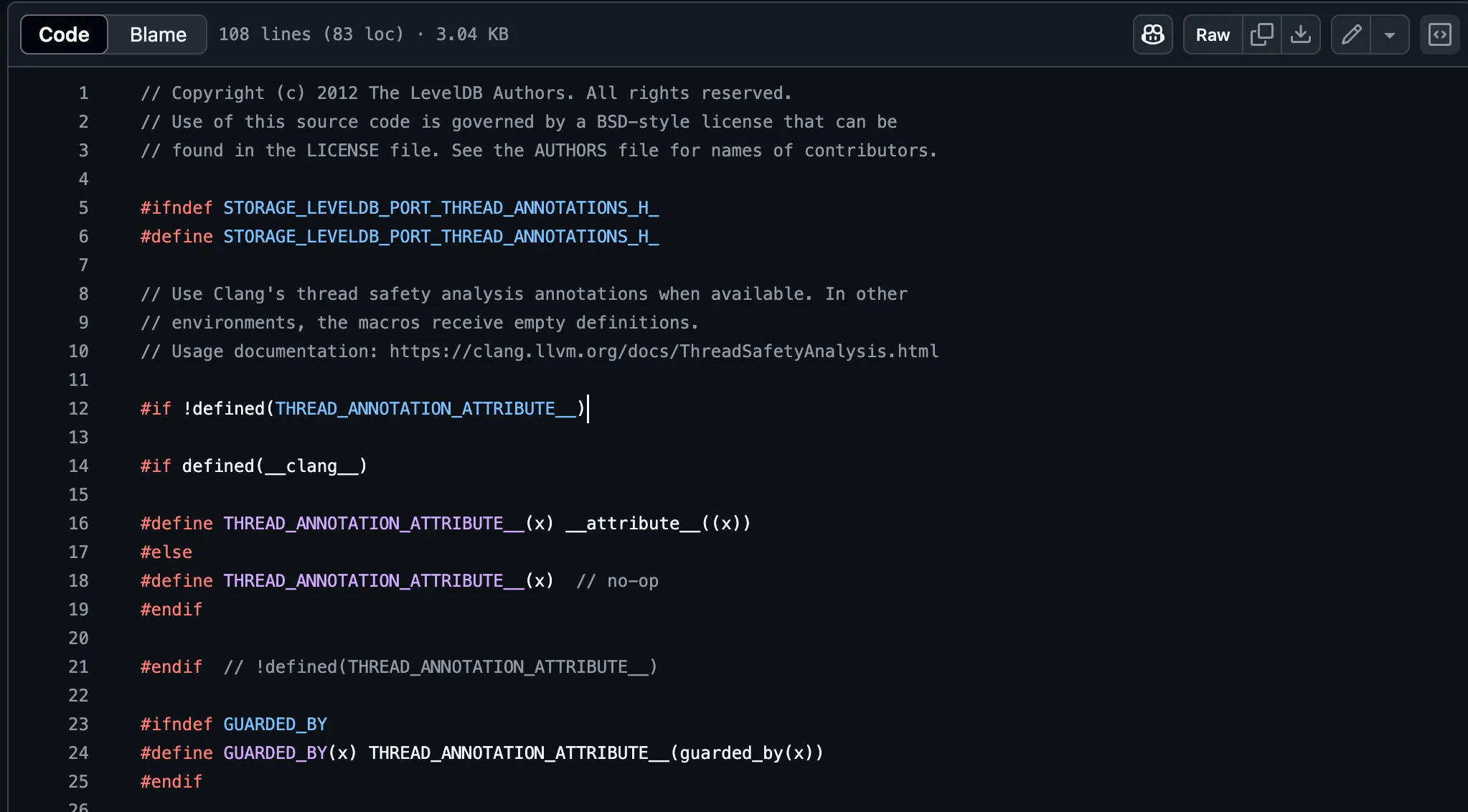

0 CommentLevelDB has some interesting macros that I rarely use in my daily coding. These macros are defined in thread_annotations.h and can be used to detect potential thread safety issues at compile time using Clang’s thread safety analysis tool.

Clang's Thread Safety Analysis Tool

Clang's Thread Safety Analysis Tool

What exactly do macros like these do? Let’s take a look together.

1 | GUARDED_BY(x) // Indicates that a variable must be accessed while holding lock x |

GUARDED_BY Lock Protection

You’ll often see annotations like GUARDED_BY(mutex_) in class member variable definitions. What’s their purpose? Take a look at the LRU Cache definition:

1 | class LRUCache { |

This is Clang’s thread safety annotation. During compilation, Clang checks that all accesses to usage_ and table_ occur while holding the mutex_ lock. Additionally, the compiler checks whether all locks that should be released are actually released at the end of functions or code blocks, helping prevent resource leaks or deadlocks due to forgotten lock releases.

In contrast, when writing business code, we rarely use these thread safety annotations. At most, we might add comments indicating that something isn’t thread-safe and needs lock protection, relying entirely on developer discipline. Unsurprisingly, this leads to various strange multi-threading data race issues in business code.

LevelDB’s implementation includes many such thread safety annotations, which not only explicitly tell other developers that a variable needs lock protection but also help detect potential thread safety issues at compile time, reducing race conditions, deadlocks, and other problems that might occur in multi-threaded environments.

Thread Annotation Example with Lock Protection

Let’s look at a complete example to see how Clang’s thread safety annotations work. In this SharedData class, the counter_ variable needs lock protection, and mutex_ is our wrapped lock implementation.

1 | // guard.cpp |

For this test code to run directly, we didn’t use the GUARDED_BY macro defined in LevelDB. The __attribute__((guarded_by(mutex_))) here expands to the same result as the macro.

When compiling this code with Clang, you’ll see warning messages:

1 | clang++ -pthread -Wthread-safety -std=c++17 guard.cpp -o guard |

As you can see, the compiler detects at compile time when the counter_ variable is accessed without holding the mutex_ lock and issues warnings.

PT_GUARDED_BY Pointer Protection

While GUARDED_BY is typically used on non-pointer members to protect the member variable itself, PT_GUARDED_BY is used on pointer and smart pointer members to protect the data being pointed to. Note that PT_GUARDED_BY only protects the data being pointed to, not the pointer itself. Here’s an example:

1 | Mutex mu; |

Capability Attribute Annotation

In the example above, we didn’t use the standard library’s mutex directly, but instead wrapped it in a simple Mutex class. The class definition uses the __attribute__((capability("mutex"))) annotation.

This is because Clang’s thread safety analysis needs to know which types are locks and track their acquisition and release states. Standard library types don’t have these annotations and can’t be used directly with Clang’s thread safety analysis. Here, we use Clang’s capability("mutex") attribute to specify that the class has lock characteristics.

LevelDB’s lock definition code also uses annotations, though slightly differently, using LOCKABLE:

1 | class LOCKABLE Mutex { |

This is because earlier versions of Clang used the lockable attribute, while the more general capability attribute was introduced later. For backward compatibility, lockable was kept as an alias for capability(“mutex”). So, they are equivalent.

Thread Safety Analysis Capabilities

The example above is a bit simple. At its core, Clang’s static thread safety analysis aims to provide a way to protect resources at compile time. These resources can be data members like counter_ from earlier, or functions/methods that provide access to certain underlying resources. Clang can ensure at compile time that unless a thread has the capability to access a resource, it cannot access that resource.

Here, thread safety analysis uses attributes to declare resource constraints, which can be attached to classes, methods, and data members. Clang officially provides a series of attribute definition macros that can be used directly. LevelDB defines its own macros, which can also be referenced.

In the previous examples, annotations were mainly used on data members, but they can also be used on functions. For example, the Mutex object defined in LevelDB uses these annotations on member functions:

1 | class LOCKABLE Mutex { |

These annotations are primarily used to mark lock object member functions, telling the compiler how these functions will change the lock’s state:

- EXCLUSIVE_LOCK_FUNCTION: Indicates that the function will acquire exclusive access to the mutex. The lock must be unheld before calling, and will be exclusively held by the current thread after calling;

- UNLOCK_FUNCTION: Indicates that the function will release the lock. The lock must be held before calling (either exclusively or shared), and will be released after calling;

- ASSERT_EXCLUSIVE_LOCK: Used to assert that the current thread holds exclusive ownership of the lock, typically used in debug code to ensure code runs in the correct locking state.

Of course, these are Clang’s early thread safety annotations, mainly named for locks. The above can now be replaced with ACQUIRE(…), ACQUIRE_SHARED(…), RELEASE(…), RELEASE_SHARED(…).

For more details about other annotations, you can refer to Clang’s official documentation on Thread Safety Analysis.