5 Real-world Cases of C++ Process Crashes from Production

If you’ve worked on any non-trivial C++ project, you’ve likely encountered process coredumps. A coredump is a mechanism where the operating system records the current memory state of a program when it encounters a severe error during execution.

There are many reasons why a C++ process might coredump, including:

- Illegal Memory Access: This includes dereferencing null pointers, accessing freed memory, array bounds violations, etc.

- Stack Overflow: Caused by infinite recursion or large arrays allocated on the stack

- Segmentation Fault: Attempting to write to read-only memory or accessing unmapped memory regions

- Uncaught Exceptions: Program termination due to unhandled exceptions

When encountering a coredump, we typically need to examine the core file for problem analysis and debugging. Analyzing core files can be challenging as it requires a deep understanding of C++’s memory model, exception handling mechanisms, and system calls.

Rather than focusing on core file analysis methods, this article will present several real-world cases to help developers proactively avoid these errors in their code.

Uncaught Exceptions

One of the most common causes of process crashes in production code is throwing exceptions without proper catch handlers. For example, when using std::stoi to convert a string to an integer, if the string cannot be converted to a number, it throws a std::invalid_argument exception. If neither the framework nor the caller catches this exception, the process will crash.

The C++ standard library has quite a few functions that may throw exceptions. Common examples include:

- std::vector::at(): Throws

std::out_of_rangefor out-of-bounds access - std::vector::push_back(): Throws

std::bad_allocif memory allocation fails - std::map::at(): Throws

std::out_of_rangeif the key doesn’t exist

When using these potentially throwing functions from the standard library, proper exception handling is crucial. For custom classes, it’s recommended to use error codes rather than exceptions for error handling. While there’s ongoing debate about exceptions versus error codes, you should follow what you’re comfortable with or your project’s conventions. For functions that are guaranteed not to throw, you can mark them with noexcept to inform both the compiler and users.

It’s worth noting that some function calls won’t throw exceptions but may lead to undefined behavior, which can also cause process crashes. For example, the atoi function exhibits undefined behavior if the string can’t be converted to a number, potentially leading to crashes in certain scenarios.

When using basic functions, if you’re unsure about their behavior, consult the cplusplus documentation to determine whether they might throw exceptions or lead to undefined behavior. For example, regarding vector:

std::vector::front()

Calling this function on an empty container causes undefined behavior.std::vector::push_back()

If a reallocation happens, the storage is allocated using the container’s allocator, which may throw exceptions on failure (for the default allocator, bad_alloc is thrown if the allocation request does not succeed).

Array Bounds Violations

Beyond exceptions, another common issue is array bounds violations. We all know that in C++, accessing an array with an out-of-bounds index leads to illegal memory access, potentially causing a process crash. You might think, “How could array access go out of bounds? I just need to check the length when iterating!”

Let’s look at a real example from production code. For demonstration purposes, I’ve simplified the actual business logic to show just the core issue:

1 |

|

Initially, the first loop initializes dest from src. After some intervening code, another loop processes dest based on src’s content.

This worked fine at first, but then a requirement was added to filter out certain values from src, leading to the addition of the if statement to skip some elements. The person making this change might not have noticed the subsequent iteration over src and dest, not realizing that filtering would cause dest’s length to differ from src’s.

This scenario can be tricky to trigger as a coredump, as it only occurs in rare cases where filtering actually results in different lengths. Moreover, even when accessing an out-of-bounds index in the second loop, using [] might not cause a crash. The example code deliberately uses at() to force a crash on out-of-bounds access.

Iterator Invalidation

Beyond array bounds violations, another common issue is iterator invalidation. The iterator pattern provides a way to access elements in a container without exposing its internal representation. In C++, iterators are a crucial concept, serving as a bridge between containers and algorithms.

Many containers in the C++ standard library provide iterators, such as vector, list, and map. When accessing these container iterators, if the iterator has been invalidated, it leads to undefined behavior and potentially causes a process crash.

There are several ways iterators can become invalid. For example, when a vector reallocates memory during expansion, all previous iterators become invalid. A classic example is trying to remove even-numbered elements from a vector, where beginners might write something like this:

1 | for (auto it = numbers.begin(); it != numbers.end(); ++it) { |

Here, when erase is called to remove an element, it invalidates all iterators at and after the deletion point. So continuing to use it in the loop leads to undefined behavior. The correct approach is to use the return value from erase to update the iterator, or use remove_if and erase to remove elements.

While this example is relatively simple, we’ve encountered more subtle iterator invalidation issues in production. In one case, we had a batch processing task using a coroutine pool to handle IO-intensive tasks and write results back to a vector. Here’s a simplified version of the code:

1 | // Simulated async processing function |

Here, we store a reference to results.back() and use it in an async task. While the async task is executing, the results vector continues to add new elements. When the vector needs to reallocate, the original memory is freed and new memory is allocated. At this point, the reference held by the async task becomes dangling, and accessing it leads to undefined behavior.

The correct approach would be to either use reserve to pre-allocate space to avoid reallocation, or store indices instead of references.

Data Races in Concurrent Code

Another category of crashes comes from data races in concurrent code. A common scenario is having a background thread in a service that pulls configuration updates from a configuration center and updates them locally. Meanwhile, multiple business threads concurrently read this configuration.

Since this is a classic read-heavy scenario, it’s typically implemented using a read-write lock. Multiple reader threads can hold the read lock simultaneously, while the writer thread needs exclusive access, ensuring no other read or write operations during writing. New read operations must wait during write operations. A possible execution sequence might look like this:

1 | Time ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────▶ |

Here, W represents a write operation, and R represents a read operation. As you can see, new read operations must wait during write operations. We encountered a crash in production due to incorrect use of read-write locks. While the actual scenario was more complex, here’s the core code simplified:

1 | class DataManager { |

The complete demonstration code is available in core_share.cpp. In loadData, we prepare the configuration data and then use a write lock to update it. In readData, we use a read lock to read the configuration.

Seems fine, right? The crash was very intermittent, and the code hadn’t been modified for a long time. We could only analyze it using the core file. Surprisingly, the core stack showed the crash occurring during the destruction of localdata in the loadData method. localdata is a local variable that swaps with m_data before destruction. This suggested that m_data’s memory layout was problematic, and m_data is only written here, with all other access being “read”.

Upon closer inspection of the code, we discovered that m_data was being read using the [] operator for unordered_map. For unordered_map, if a key doesn’t exist, [] will insert a default value. Aha! While we intended to protect read-only operations with a read lock, we accidentally performed write operations. As we know, concurrent writes to unordered_map cause data races, which explains the crashes.

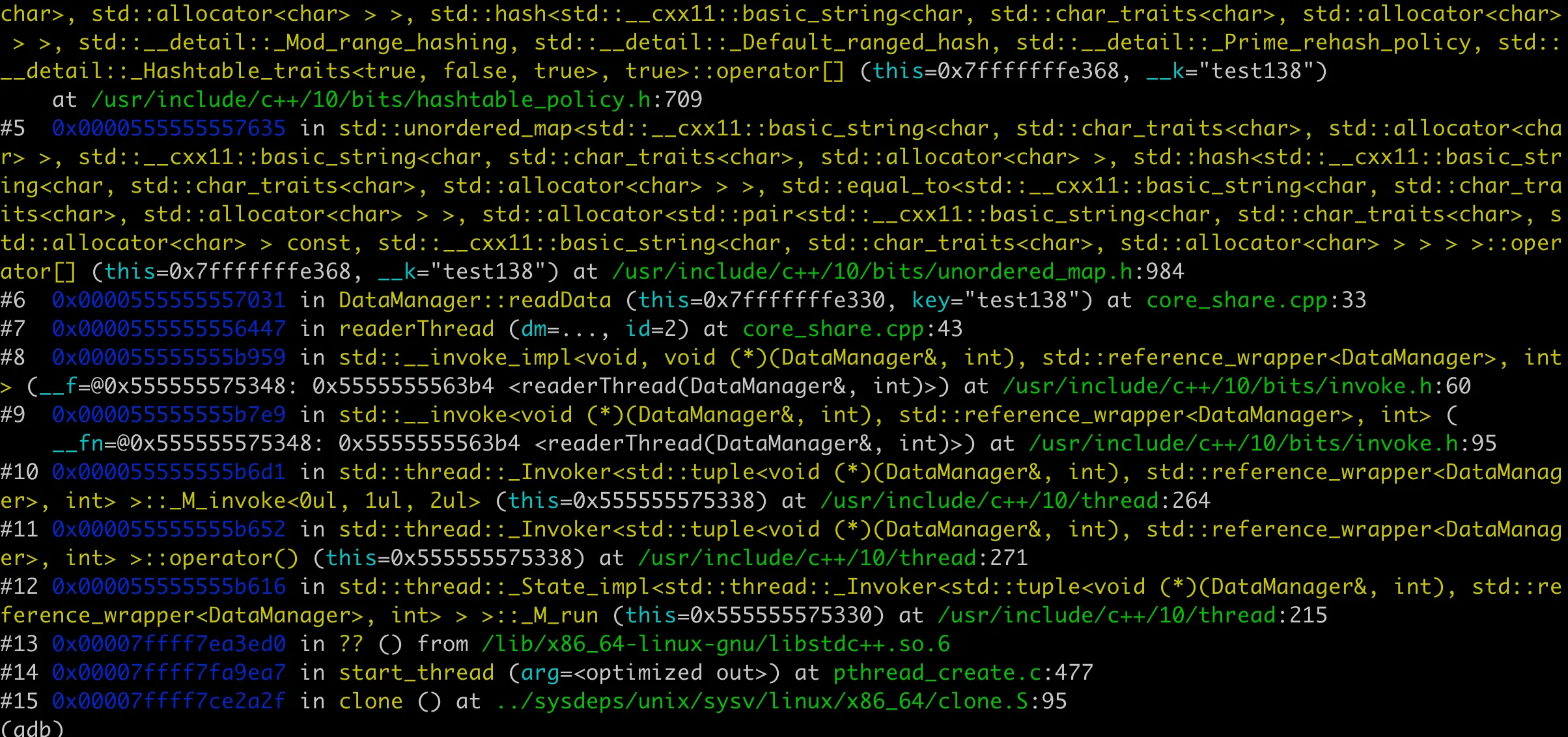

Of course, the core stack might not always show the destruction point. For example, in our demonstration code, the stack shows the crash in the reader thread’s readData, as shown in this image:

Catastrophic Backtracking Leading to Stack Overflow

The examples above are relatively easy to avoid with proper attention. However, the following issue is less well-known and easier to overlook.

We needed to check if a string contained a pair of parentheses, so we used C++ regular expressions. Here’s a simplified version of the code:

1 |

|

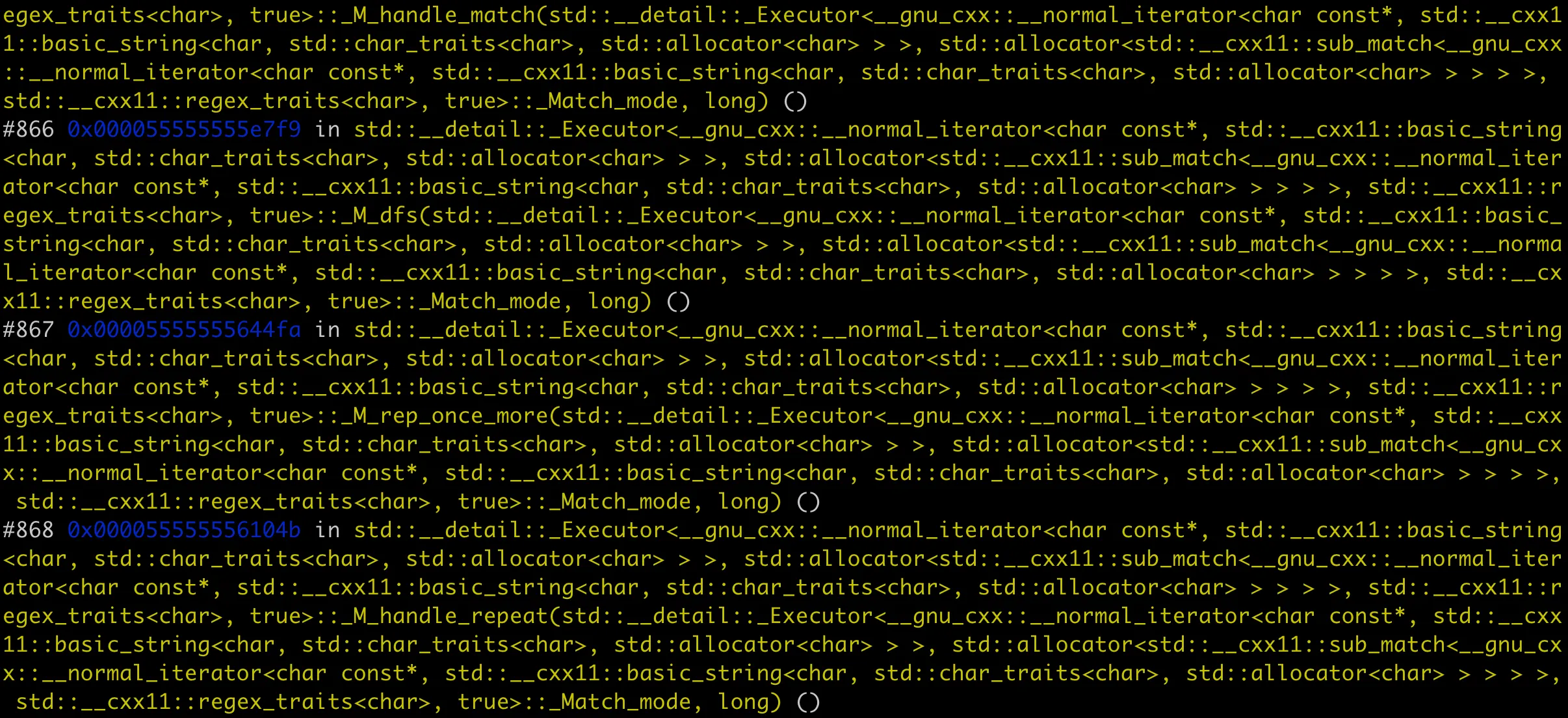

In this code, we construct a very long string and use a regular expression to match it. When compiled with g++ and executed, the program crashes. Looking at the stack trace in gdb shows:

Stack Overflow Due to Catastrophic Backtracking

Stack Overflow Due to Catastrophic Backtracking

This happens because the regex engine performs extensive backtracking, creating new stack frames for each backtrack operation. Eventually, the stack depth exceeds the stack size limit, causing the process to crash.

This is known as Catastrophic Backtracking. In real-world development, it’s best to limit input length when dealing with complex text processing. If possible, use loops or other non-recursive solutions instead of regular expressions. If regular expressions are necessary, limit repetition counts (use {n,m} instead of + or *) and avoid nested repetitions (like (.+)+).

The regular expression could be modified to:

1 | std::regex re(R"(\([^\)]{1,100}\))"); |

Of course, beyond recursive backtracking, other scenarios can cause stack overflow, such as infinite recursion or large arrays allocated on the stack. Fortunately, stack overflow issues are relatively easy to diagnose when you have a core file.

Analyzing Coredump Issues

When encountering crashes, we typically need to examine the core file. In production environments, if the business process uses significant memory, saving a core file after a crash might take considerable time. Production environments usually have watchdog processes that periodically check business processes, and if a process becomes unresponsive, some watchdogs use kill -9 to terminate and restart the process. In such cases, we might get an incomplete core file that was only partially written. The solution is to modify the watchdog process to wait for the core file to complete before restarting the process.

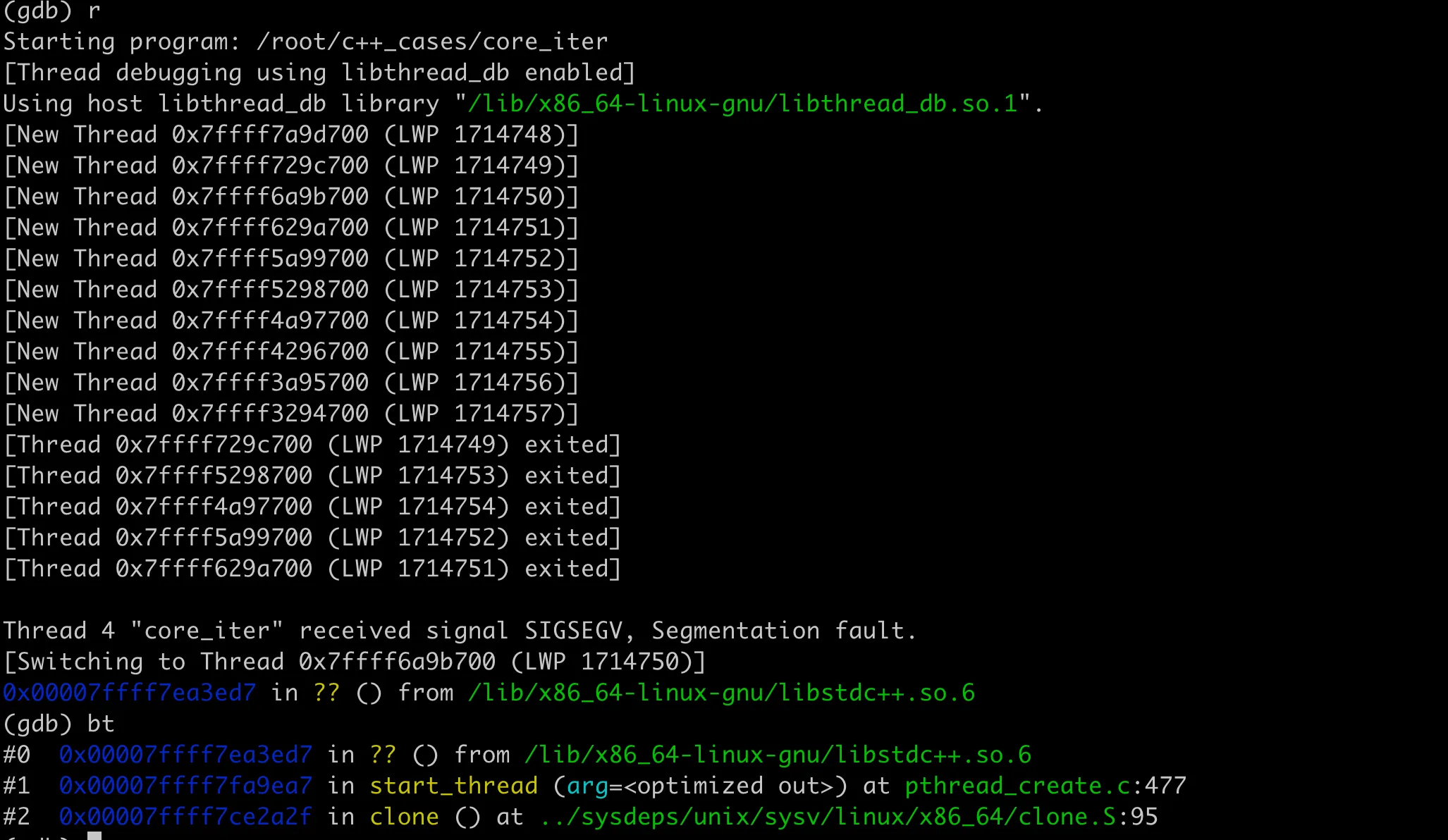

Once we have the core file, we analyze it using gdb. If the stack trace is clear, we can usually identify the issue quickly. However, often the stack trace might be incomplete, showing a series of ??. For example, with the iterator invalidation issue above, running with gdb shows this stack trace:

Iterator Invalidation Stack Trace

Iterator Invalidation Stack Trace

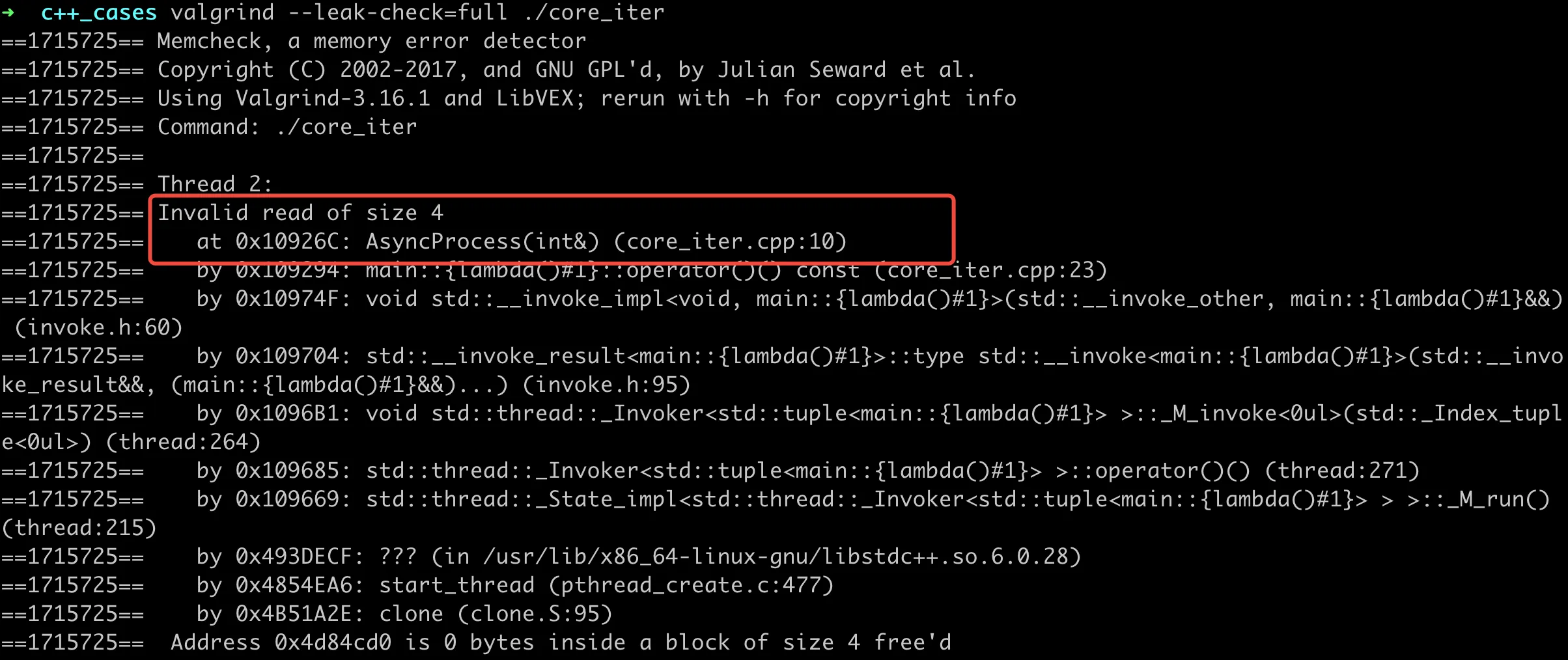

This stack trace provides little useful information and is difficult to analyze. For issues that can be reliably reproduced like our example, using Valgrind for analysis can make it easier to locate the problem. The analysis results for the above code show:

Valgrind Analysis of Iterator Invalidation

Valgrind Analysis of Iterator Invalidation

The analysis results show two main issues: Invalid read and Invalid write. The problematic code lines are clearly indicated, making it easy to locate the issue.

Summary

This article has covered five classic cases of process crashes that I’ve encountered:

Uncaught Exceptions: When using standard library functions, be aware of potential exceptions. Handle exceptions properly for functions that might throw them. For custom classes, consider using error codes instead of exceptions.

Array Bounds Violations: When working with arrays or containers, carefully check index validity. Especially when iterating over the same container multiple times, ensure its size hasn’t changed. Consider using the

at()method for bounds-checked access.Iterator Invalidation: When using iterators, be aware that container operations (like deletion or insertion) can invalidate them. For vectors, reallocation invalidates all iterators; understand the invalidation rules for other containers as well.

Data Races in Concurrent Code: In multi-threaded environments, pay special attention to concurrent data access. Even seemingly read-only operations (like map’s [] operator) might modify container contents. Use appropriate synchronization mechanisms (like mutexes or read-write locks) to protect shared data.

Stack Overflow from Catastrophic Backtracking: When using regular expressions or other potentially recursive operations, be mindful of input limitations. For complex text processing, prefer non-recursive solutions or limit recursion depth.

Of course, there are other less common causes of crashes, such as the one I previously encountered: C++ Process Coredump Analysis Due to Missing Bazel Dependencies. If you’ve encountered any memorable crash cases, feel free to share them in the comments.