LevelDB Explained - Understanding Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC)

0 CommentIn database systems, concurrent access is a common scenario. When multiple users read and write to a database simultaneously, ensuring the correctness of each person’s read and write results becomes a challenge that concurrency control mechanisms need to address.

Consider a simple money transfer scenario: account A initially has $1000 and needs to transfer $800 to account B. The transfer process includes two steps: deducting money from account A and adding money to account B. If someone queries the balances of accounts A and B between these two steps, what would they see?

Without any concurrency control, the query would reveal an anomaly: account A has been debited by $800, leaving only $200, while account B hasn’t yet received the transfer, still showing its original amount! This is a typical data inconsistency problem. To solve this issue, database systems need some form of concurrency control mechanism.

The most intuitive solution is locking – when someone is performing a write operation (such as a transfer), others’ read operations must wait. Returning to our example, only after both steps of the transfer are completed can users query the correct account balances. However, locking mechanisms have obvious drawbacks: whenever a key is being written, all read operations on that key must wait in line, limiting concurrency and resulting in poor performance.

Modern database systems widely adopt MVCC for concurrency control, and LevelDB is no exception. Let’s examine LevelDB’s MVCC implementation through its source code.

Concurrency Control Through MVCC

MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control) is a concurrency control mechanism that enables concurrent access by maintaining multiple versions of data. Simply put, LevelDB’s MVCC implementation has several key points:

- Each key can have multiple versions, each with its own sequence number;

- Write operations create new versions instead of directly modifying existing data. Different writes need to be mutually exclusive with locks to ensure each write gets an incremental version number;

- Different read operations can run concurrently without locks. Multiple read operations can also run concurrently with write operations without locks;

- Isolation between reads and writes, or between different reads, is achieved through snapshots, with read operations always seeing data versions from a specific point in time.

This is the core idea of MVCC. Let’s understand how MVCC works through a specific operation sequence. Assume we have the following operations:

1 | Time T1: sequence=100, write key=A, value=1 |

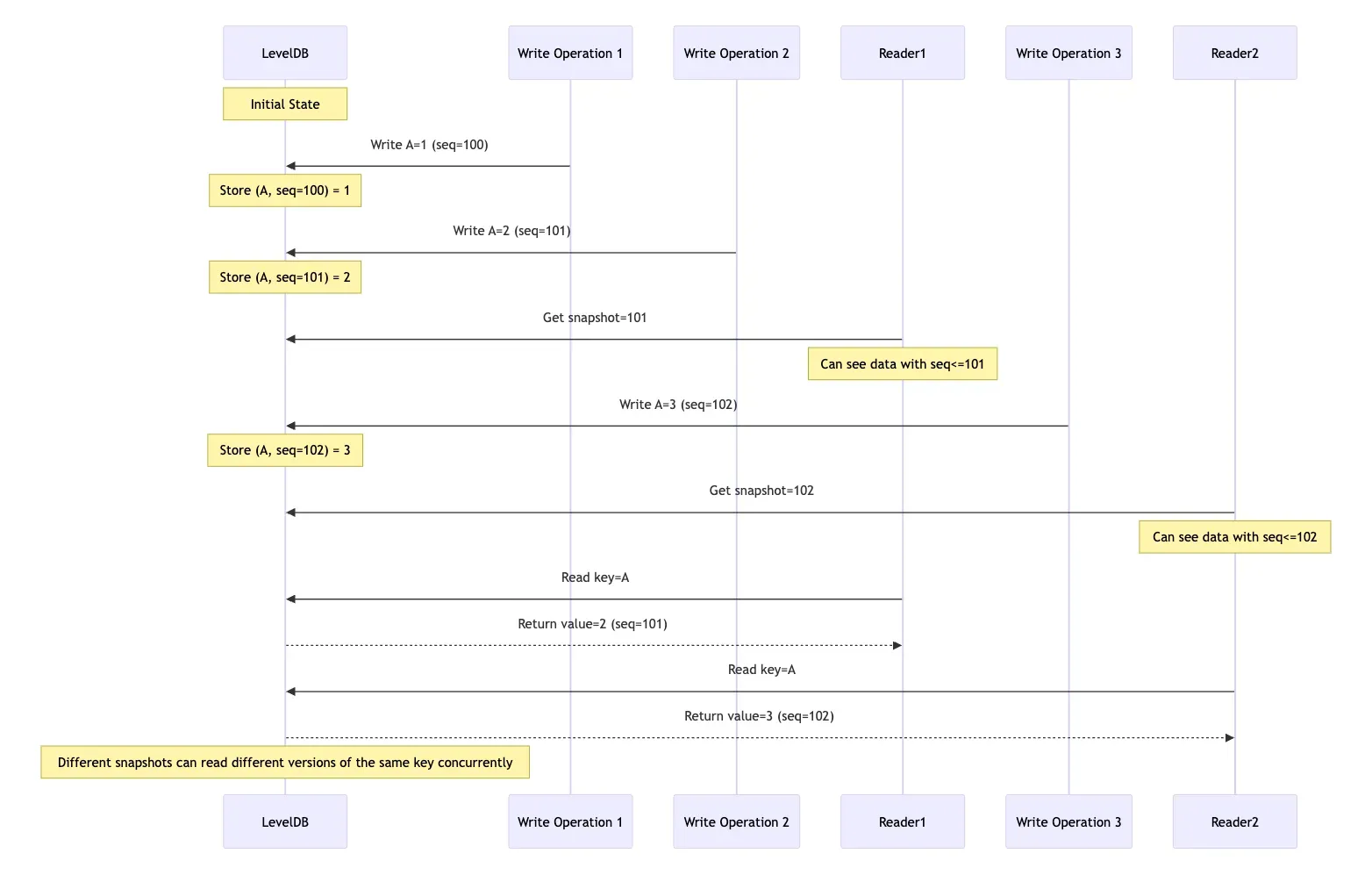

Regardless of whether Reader1 or Reader2 reads first, Reader1 reading key=A will always get value=2 (sequence=101), while Reader2 reading key=A will get value=3 (sequence=102). If there are subsequent reads without specifying a snapshot, they will get the latest data. The sequence diagram below makes this easier to understand; the mermaid source code is here:

LevelDB Read/Write MVCC Operation Sequence Diagram

LevelDB Read/Write MVCC Operation Sequence Diagram

The overall effect of MVCC is as shown above, which is relatively straightforward. Now let’s look at how MVCC is implemented in LevelDB.

LevelDB’s Versioned Key Format

A prerequisite for implementing MVCC is that each key maintains multiple versions. Therefore, we need to design a data structure that associates keys with version numbers. LevelDB’s key format is as follows:

[key][sequence<<8|type]

LevelDB’s approach is quite easy to understand – it appends version information to the original key. This version information is a 64-bit unsigned integer, with the high 56 bits storing the sequence and the low 8 bits storing the operation type. Currently, there are only two operation types, corresponding to write and delete operations.

1 | // Value types encoded as the last component of internal keys. |

Since the sequence number is only 56 bits, it can support at most writes. Could this be a problem? Would it fail if I want to write more keys? Theoretically yes, but let’s analyze from a practical usage perspective. Assuming 1 million writes per second (which is already a very high write QPS), the duration this system could sustain writes would be:

Well… it can handle writes for over 2000 years, so this sequence number is sufficient, and there’s no need to worry about depletion. Although the data format design is quite simple, it has several advantages:

- The same key supports different versions – when the same key is written multiple times, the most recent write will have a higher sequence number. Concurrent reads of older versions of this key are supported during writes.

- The type field distinguishes between normal writes and deletions, so deletion doesn’t actually remove data but writes a deletion marker, with actual deletion occurring only during compaction.

We know that keys in LevelDB are stored in sequence. When querying a single key, binary search can quickly locate it. When obtaining a series of consecutive keys, binary search can quickly locate the starting point of the range, followed by sequential scanning. But now that we’ve added version numbers to the keys, the question arises: how do we sort keys with version numbers?

Internal Key Sorting Method

LevelDB’s approach is relatively simple and effective, with the following sorting rules:

- First, sort by key in ascending order, using lexicographical ordering of strings

- Then, sort by sequence number in descending order, with larger sequence numbers coming first

- Finally, sort by type in descending order, with write types coming before deletion types

To implement these sorting rules, LevelDB created its own comparator in db/dbformat.cc, with the following code:

1 | int InternalKeyComparator::Compare(const Slice& akey, const Slice& bkey) const { |

We can see that it first removes the last 8 bits from the versioned key to get the actual user key, and then compares according to the user key’s sorting rules. Additionally, LevelDB provides a default user key comparator, leveldb.BytewiseComparator, which compares keys based entirely on their byte sequence. The comparator implementation code is in util/comparator.cc:

1 | class BytewiseComparatorImpl : public Comparator { |

Here, Slice is a string class defined in LevelDB to represent a string, and its compare method performs a byte-by-byte comparison. In fact, LevelDB also supports user-defined comparators – users just need to implement the Comparator interface. When using comparators, BytewiseComparator is wrapped in a singleton, with code that might be a bit difficult to understand:

1 | const Comparator* BytewiseComparator() { |

I previously wrote an article specifically explaining the NoDestructor template class, for those interested: LevelDB Explained - Preventing C++ Object Destruction.

The benefits of this sorting approach are evident: first, sorting user keys in ascending order makes range queries highly efficient. When users need to retrieve a series of consecutive keys, they can use binary search to quickly locate the starting point of the range, followed by sequential scanning. Additionally, multiple versions of the same user key are sorted by sequence number in descending order, meaning the newest version comes first, facilitating quick access to the current value. During a query, it only needs to find the first version with a sequence number less than or equal to the current snapshot’s, without having to scan all versions completely.

That’s enough about sorting. Now, let’s look at how keys are assembled during read and write operations.

Writing Versioned Keys

The process of writing key-value pairs in LevelDB is quite complex; you can refer to my previous article: LevelDB Explained - Implementation and Optimization Details of Key-Value Writing. Simply put, data is first written to the memtable, then to the immutable memtable, and finally gradually settled (compacted) into SST files at different levels. The first step of the entire process is writing to the memtable, so at the beginning of writing to the memtable, the key is tagged with a version and type, assembled into the versioned internal key format we mentioned earlier.

The code for assembling the key is in the MemTable::Add function in db/memtable.c. In addition to assembling the key, it also concatenates the value part. The implementation is as follows:

1 | void MemTable::Add(SequenceNumber s, ValueType type, const Slice& key, |

Here we can see that multiple writes of the same user key produce multiple versions, each with a unique sequence number. Once a user key is converted to an internal key, all subsequent processing is based on this internal key, including MemTable conversion to Immutable MemTable, SST file writing, SST file merging, and so on.

In the Add function, the length of the internal key is also stored before the internal key itself, and the length and internal key are concatenated and inserted into the MemTable together. This key is actually a memtable_key, which is also used for searching in the memtable during reading.

Why do we need to store the length here? We know that the SkipList in Memtable uses const char* pointers as the key type, but these pointers are just raw pointers to certain positions in memory. When the skiplist’s comparator needs to compare two keys, it needs to know the exact range of each key – that is, the start and end positions. If we directly use the internal key, there’s no clear way to know the exact boundaries of an internal key in memory. With length information added, we can quickly locate the boundaries of each key, allowing for correct comparison.

Key-Value Reading Process

Next, let’s look at the process of reading key-values. When reading key-values, the user key is first converted to an internal key, and then a search is performed. However, the first issue here is which sequence number to use. Before answering this question, let’s look at the common method for reading keys:

1 | std::string newValue; |

There’s a ReadOptions parameter here, which encapsulates a Snapshot object. You can understand this snapshot as the state of the database at a particular point in time, containing all the data before that point but not including writes after that point.

The core implementation of the snapshot is actually saving the maximum sequence number at a certain point in time. When reading, this sequence number is used to assemble the internal key. There are two scenarios during reading: if no snapshot is specified, the latest sequence number is used; if a previously saved snapshot is used, the sequence number of that snapshot is used.

Then, based on the snapshot sequence number and user key, assembly occurs. Here, a LookupKey object is first defined to encapsulate some common operations when using internal keys for lookups. The code is in db/dbformat.h:

1 | // A helper class useful for DBImpl::Get() |

In the LookupKey constructor, the internal key is assembled based on the passed user_key and sequence, with the specific code in db/dbformat.cc. When searching in the memtable, memtable_key is used, and when searching in the SST, internal_key is used. The memtable_key here is what we mentioned earlier – adding length information before the internal_key to facilitate quick location of each key’s boundaries in the SkipList.

If the key is not found in the memtable and immutable memtable, it will be searched for in the SST. Searching in the SST is considerably more complex, involving the management of multi-version data. I will write a dedicated article to explain this reading process in the future.

Conclusion

This article’s explanation of MVCC is still relatively basic, introducing the general concept and focusing on how sequence numbers are processed during read and write operations. It hasn’t delved into multi-version data management or the process of cleaning up old version data. We’ll explore these topics in future articles.

In summary, LevelDB implements multi-version concurrency control by introducing version numbers into key-values. It achieves read isolation through snapshots, with writes always creating new versions. For read operations, no locks are needed, allowing concurrent reading. For write operations, locks are required to ensure the order of writes.

This design provides excellent concurrent performance, ensures read consistency, and reduces lock contention. However, the trade-offs are additional storage space overhead and the code complexity that comes with maintaining multiple versions.