LevelDB Explained - The Implementation Details of a High-Performance LRU Cache

0 CommentIn computer systems, caches are ubiquitous. From CPU caches to memory caches, from disk caches to network caches, they are everywhere. The core idea of a cache is to trade space for time by storing frequently accessed “hot” data in high-performance storage to improve performance. Since caching devices are expensive, their storage size is limited, which means some cached data must be evicted. The eviction policy is crucial here; an unreasonable policy might evict data that is about to be accessed, leading to a very low cache hit rate.

There are many cache eviction policies, such as LRU, LFU, and FIFO. Among them, LRU (Least Recently Used) is a classic strategy. Its core idea is: when the cache is full, evict the least recently used data. This is based on the empirical assumption that “if data has been accessed recently, it is more likely to be accessed again in the future.” As long as this assumption holds, LRU can significantly improve the cache hit rate.

LevelDB implements an in-memory LRU Cache to store hot data, enhancing read and write performance. By default, LevelDB caches sstable indexes and data blocks. The sstable cache is configured to hold 990 (1000-10) entries, while the data block cache is allocated 8MB by default.

The LRU cache implemented in LevelDB is a sharded LRU with many detailed optimizations, making it an excellent case study. This article will start with the classic LRU implementation and then progressively analyze the implementation details of LevelDB’s LRU Cache.

Classic LRU Implementation

A well-implemented LRU needs to support insertion, lookup, and deletion operations in time complexity. The classic approach uses a doubly linked list and a hash table:

- The doubly linked list stores the cache entries and maintains their usage order. Recently accessed items are moved to the head of the list, while the least recently used items gradually move towards the tail. When the cache reaches its capacity and needs to evict data, the item at the tail of the list (the least recently used item) is removed.

- The hash table stores the mapping from keys to their corresponding nodes in the doubly linked list, allowing any data item to be accessed and located in constant time. The hash table’s keys are the data item keys, and the values are pointers to the corresponding nodes in the doubly linked list.

The doubly linked list ensures constant-time node addition and removal, while the hash table provides constant-time data access. For a get operation, the hash table quickly locates the node in the list. If it exists, it’s moved to the head of the list, marking it as recently used. For an insert operation, if the data already exists, its value is updated, and the node is moved to the head. If it doesn’t exist, a new node is inserted at the head, a mapping is added to the hash table, and if the capacity is exceeded, the tail node is removed from the list and its mapping is deleted from the hash table.

This implementation approach is familiar to anyone who has studied algorithms. There are LRU implementation problems on LeetCode, such as 146. LRU Cache, which requires implementing the following interface:

1 | class LRUCache { |

However, implementing an industrial-grade, high-performance LRU cache is still quite challenging. Next, let’s see how LevelDB does it.

Cache Design: Dependency Inversion

Before diving into LevelDB’s LRU Cache implementation, let’s look at how the cache is used. For example, in db/table_cache.cc, to cache SSTable metadata, the TableCache class defines a member variable of type Cache and uses it to perform various cache operations.

1 | Cache* cache_(NewLRUCache(entries)); |

Here, Cache is an abstract class that defines the various interfaces for cache operations, as defined in include/leveldb/cache.h. It specifies basic operations like Insert, Lookup, Release, and Erase. It also defines the Cache::Handle type to represent a cache entry. User code interacts only with this abstract interface, without needing to know the concrete implementation.

Then there is the LRUCache class, which is the concrete implementation of a complete LRU cache. This class is not directly exposed to the outside world, nor does it directly inherit from Cache. There is also a ShardedLRUCache class that inherits from Cache and implements the cache interfaces. It contains 16 LRUCache “shards,” each responsible for caching a portion of the data.

This design allows callers to easily swap out different cache implementations without modifying the code that uses the cache. Ha, isn’t this the classic Dependency Inversion Principle from SOLID object-oriented programming? The application layer depends on an abstract interface (Cache) rather than a concrete implementation (LRUCache). This reduces code coupling and improves the system’s extensibility and maintainability.

When using the cache, a factory function is used to create the concrete cache implementation, ShardedLRUCache:

1 | Cache* NewLRUCache(size_t capacity) { return new ShardedLRUCache(capacity); } |

LRUCache is the core part of the cache, but for now, let’s put aside its implementation and first look at the design of the cache entry, Handle.

LRUHandle Class Implementation

In LevelDB, a cached data item is an LRUHandle class, defined in util/cache.cc. The comments here explain that LRUHandle is a heap-allocated, variable-length structure that is stored in a doubly-linked list, ordered by access time. Let’s look at the members of this struct:

1 | struct LRUHandle { |

This is a bit complex, and each field is quite important. Let’s go through them one by one.

- value: Stores the actual value of the cache entry. It’s a

void*pointer, meaning the cache layer is agnostic to the value’s structure; it only needs the object’s address. - deleter: A function pointer to a callback used to delete the cached value. When a cache entry is removed, this is used to free the memory of the cached value.

- next_hash: The LRU cache implementation requires a hash table. LevelDB implements its own high-performance hash table. As we discussed in LevelDB Explained - How to Design a High-Performance HashTable, the next_hash field of LRUHandle is used to resolve hash collisions.

- prev/next: Pointers to the previous/next node in the doubly linked list, used to maintain the list for fast insertion and deletion of nodes.

- charge: Represents the cost of this cache entry (usually its memory size), used to calculate the total cache usage and determine if eviction is necessary.

- key_length: The length of the key, used to construct a Slice object representing the key.

- in_cache: A flag indicating whether the entry is in the cache. If true, it means the cache holds a reference to this entry.

- refs: A reference count, including the cache’s own reference (if in the cache) and references from users. When the count drops to 0, the entry can be deallocated.

- hash: The hash value of the key, used for fast lookups and sharding. Storing the hash value here avoids re-computation for the same key.

- key_data: A flexible array member that stores the actual key data. malloc is used to allocate enough space to store the entire key. We also discussed flexible array members in LevelDB Explained - Understanding Advanced C++ Techniques.

The design of LRUHandle allows the cache to efficiently manage data items, track their references, and implement the LRU eviction policy. In particular, the combination of the in_cache and refs fields allows us to distinguish between items that are “cached but not referenced by clients“ and those that are “referenced by clients,” enabling an efficient eviction strategy using two linked lists.

Next, we’ll examine the implementation details of the LRUCache class to better understand the purpose of these fields.

LRUCache Class Implementation Details

Having looked at the design of the cache entry, we can now examine the concrete implementation details of LevelDB’s LRUCache. The core caching logic is implemented in the LRUCache class in util/cache.cc. This class contains the core logic for operations like insertion, lookup, deletion, and eviction.

The comments here (LevelDB’s comments are always worth reading carefully) mention that it uses two doubly linked lists to maintain cache items. Why is that?

1 | // The cache keeps two linked lists of items in the cache. All items in the |

Why Use Two Doubly Linked Lists?

As mentioned earlier, a typical LRU Cache implementation uses a single doubly linked list. Each time a cache item is used, it’s moved to the head of the list, making the tail the least recently used item. For eviction, the node at the tail is simply removed. The LeetCode problem mentioned earlier can be solved this way, where each cache item is just an int, and its value is copied on access. If the cached items are simple value types that can be copied directly on read without needing references, a single linked list is sufficient.

However, in LevelDB, the cached data items are LRUHandle objects, which are dynamically allocated, variable-length structures. For high concurrency and performance, they cannot be managed by simple value copying but must be managed through reference counting. If we were to use a single linked list, consider this scenario.

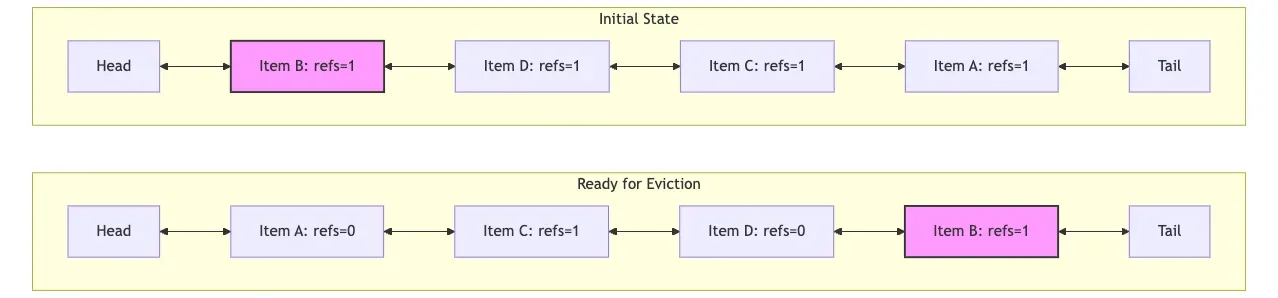

We access items A, C, and D in order, and finally access B. Item B is referenced by a client (refs > 1) and is at the head of the list, as shown in the initial state in the diagram below. Over time, A, C, and D are accessed, but B is not. According to the LRU rule, A, C, and D are moved to the head. Although B is still referenced, its relative position moves towards the tail because it hasn’t been accessed for a long time. After A and D are accessed and quickly released, they have no external references. When eviction is needed, we start from the tail and find that item B (refs > 1) cannot be evicted. We would have to skip it and continue traversing the list to find an evictable item.

LRUCache Doubly Linked List State

LRUCache Doubly Linked List State

In other words, in this reference-based scenario, when evicting a node, if the node at the tail of the list is currently referenced externally (refs > 1), it cannot be evicted. This requires traversing the list to find an evictable node, which is inefficient. In the worst case, if all nodes are referenced, the entire list might be traversed without being able to evict anything.

To solve this problem, the LRUCache implementation uses two doubly linked lists. One is in_use_, which stores referenced cache items. The other is lru_, which stores unreferenced cache items. Each cache item can only be in one of these lists at a time, never both. However, an item can move between the two lists depending on whether it’s currently referenced. This way, when a node needs to be evicted, it can be taken directly from the lru_ list without traversing the in_use_ list.

That’s the introduction to the dual linked list design. We’ll understand it better by looking at the core implementation of LRUCache.

Cache Insertion, Deletion, and Lookup

Let’s first look at node insertion, implemented in util/cache.cc. In short, an LRUHandle object is created, placed in the in_use_ doubly linked list, and the hash table is updated. If the cache capacity is reached after insertion, a node needs to be evicted. However, the implementation has many subtle details, and LevelDB’s code is indeed concise.

Let’s look at the parameters: key and value are passed by the client, hash is the hash of the key, charge is the cost of the cache item, and deleter is the callback function for deleting the item. Since LRUHandle has a flexible array member at the end, we first manually calculate the size of the LRUHandle object, allocate memory, and then initialize its members. Here, refs is initialized to 1 because a Handle pointer is returned.

1 | Cache::Handle* LRUCache::Insert(const Slice& key, uint32_t hash, void* value, |

The next part is also interesting. LevelDB’s LRUCache implementation supports a cache capacity of 0, which means no data is cached. To cache an item, in_cache is set to true, and the refs count is incremented because the Handle object is placed in the in_use_ list. The handle is also inserted into the hash table. Note the FinishErase call here, which is worth discussing.

1 | if (capacity_ > 0) { |

As we discussed in the hash table implementation, if a key already exists when inserting into the hash table, the old Handle object is returned. The FinishErase function is used to clean up this old Handle object.

1 | // If e != nullptr, finish removing *e from the cache; it has already been |

The cleanup involves several steps. First, the old handle is removed from either the in_use_ or lru_ list. It’s not certain which list the old Handle object is in, but that’s okay—LRU_Remove can handle it without knowing which list it’s in. The LRU_Remove function is very simple, just two lines of code. If you’re unsure, try drawing a diagram:

1 | void LRUCache::LRU_Remove(LRUHandle* e) { |

Next, in_cache is set to false, indicating it’s no longer in the cache. Then, the cache capacity is updated by decrementing usage_. Finally, Unref is called to decrement the reference count of this Handle object, which might still be referenced elsewhere. Only when all references are released will the Handle object be truly deallocated. The Unref function is also quite interesting; I’ll post the code here:

1 | void LRUCache::Unref(LRUHandle* e) { |

First, the count is decremented. If it becomes 0, it means there are no external references, and the memory can be safely deallocated. Deallocation has two parts: first, the deleter callback is used to clean up the memory for the value, and then free is used to release the memory for the LRUHandle pointer. If the count becomes 1 and the handle is still in the cache, it means only the cache itself holds a reference. In this case, the Handle object needs to be removed from the in_use_ list and moved to the lru_ list. If a node needs to be evicted later, this node in the lru_ list can be evicted directly.

Now for the final step of the insertion operation: checking if the cache has remaining capacity. If not, eviction begins. As long as the capacity is insufficient, the node at the head of the lru_ list is taken, removed from the hash table, and then cleaned up using FinishErase. Checking if the doubly linked list is empty is also interesting; it uses a dummy node, which we’ll discuss later.

1 | while (usage_ > capacity_ && lru_.next != &lru_) { |

The entire insertion function, including the eviction logic, and indeed the entire LevelDB codebase, is filled with assert statements for various checks, ensuring that the process terminates immediately if something goes wrong, preventing error propagation.

After seeing insertion, deletion is straightforward. The implementation is simple: remove the node from the hash table and then call FinishErase to clean it up.

1 | void LRUCache::Erase(const Slice& key, uint32_t hash) { |

Node lookup is also relatively simple. It looks up directly from the hash table. If found, the reference count is incremented, and the Handle object is returned. Just like insertion, returning a Handle object increments its reference count. So, if it’s not used externally, you must remember to call the Release method to manually release the reference, otherwise, you could have a memory leak.

1 | Cache::Handle* LRUCache::Lookup(const Slice& key, uint32_t hash) { |

Additionally, the Cache interface also implements a Prune method for proactively cleaning the cache. The method is similar to the cleanup logic in insertion, but it clears out all nodes in the lru_ list. This function is not used anywhere in LevelDB.

Doubly Linked List Operations

Let’s discuss the doubly linked list operations in more detail. We already know there are two lists: lru_ and in_use_. The comments make it clearer:

1 | // Dummy head of LRU list. |

The lru_ member is the list’s dummy node. Its next member points to the oldest cache item in the lru_ list, and its prev member points to the newest. In the LRUCache constructor, the next and prev of lru_ both point to itself, indicating an empty list. Remember how we checked for evictable nodes during insertion? It was with lru_.next != &lru_.

1 | LRUCache::LRUCache() : capacity_(0), usage_(0) { |

A dummy node is a technique used in many data structure implementations to simplify boundary condition handling. In the context of an LRU cache, a dummy node is mainly used as the head of the list, so the head always exists, even when the list is empty. This approach simplifies insertion and deletion operations because you don’t need special handling for an empty list.

For example, when adding a new element to the list, you can insert it directly between the dummy node and the current first element without checking if the list is empty. Similarly, when deleting an element, you don’t have to worry about updating the list head after deleting the last element, because the dummy node is always there.

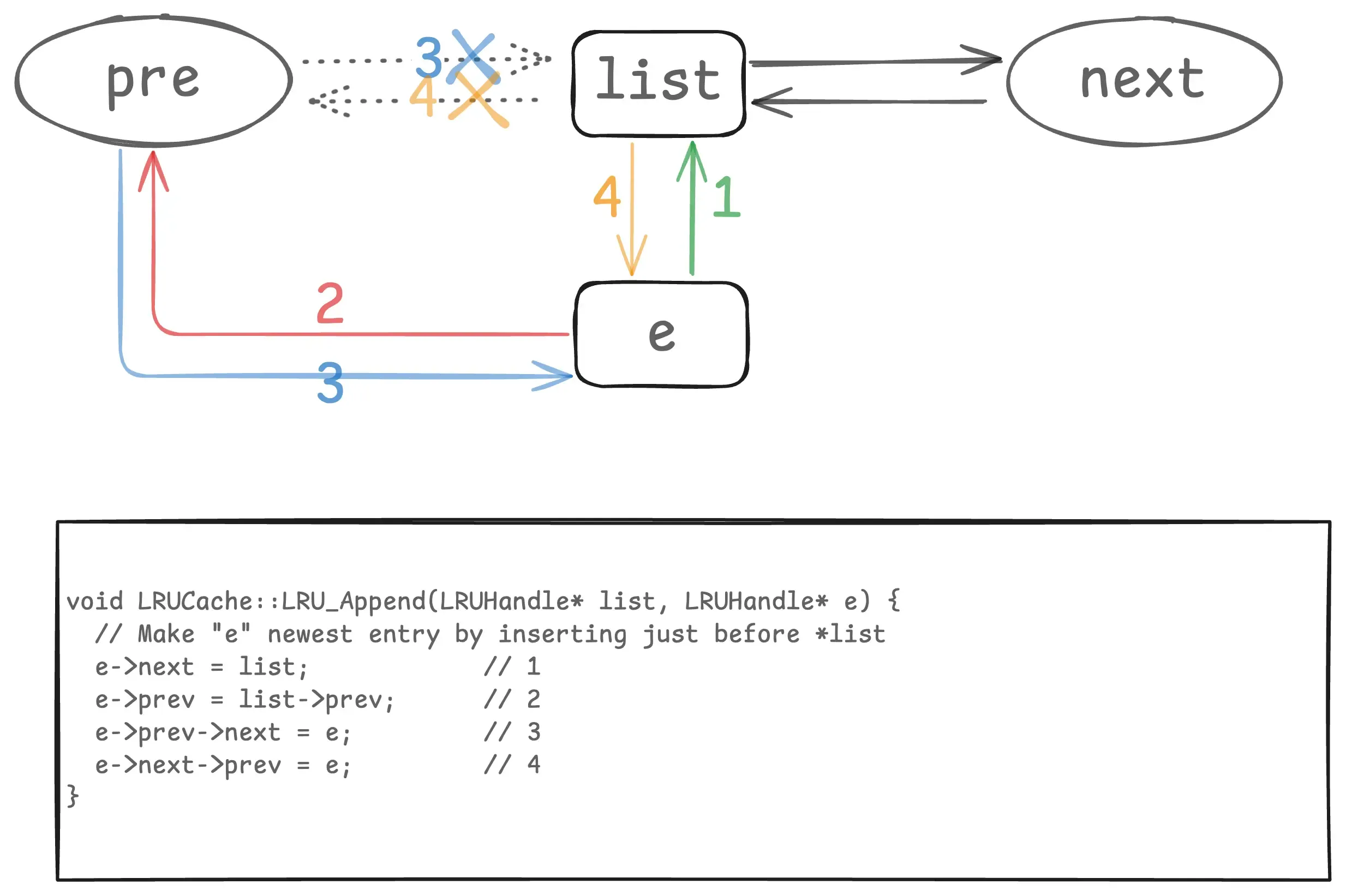

We’ve already seen LRU_Remove, which is just two lines of code. For adding a node to the list, I’ve created a diagram that, combined with the code, should make it easy to understand:

LRUCache Doubly Linked List Operations

LRUCache Doubly Linked List Operations

Here, e is the new node being inserted, and list is the dummy node of the list. I’ve used circles for list’s prev and next to indicate they can point to list itself, as in an initial empty list. The insertion happens before the dummy node, so list->prev is always the newest node in the list, and list->next is always the oldest. For this kind of list manipulation, drawing a diagram makes everything clear.

reinterpret_cast Conversion

Finally, let’s briefly touch on the use of reinterpret_cast in the code to convert between LRUHandle* and Cache::Handle*. reinterpret_cast forcibly converts a pointer of one type to a pointer of another type without any type checking. It doesn’t adjust the underlying data; it just tells the compiler: “Treat this memory address as if it were of this other type.” This operation is generally dangerous and not recommended.

However, LevelDB does this to separate the interface from the implementation. It exposes the concrete internal data structure LRUHandle* to external users as an abstract, opaque handle Cache::Handle*, while internally converting this opaque handle back to the concrete data structure for operations.

In this specific, controlled design pattern, it is completely safe. This is because only the LRUCache internal code can create an LRUHandle. Any Cache::Handle* returned to an external user always points to a valid LRUHandle object. Any Cache::Handle* passed to LRUCache must have been previously returned by the same LRUCache instance.

As long as these conventions are followed, reinterpret_cast is just switching between “views” of the pointer; the pointer itself always points to a valid, correctly typed object. If a user tries to forge a Cache::Handle* or pass in an unrelated pointer, the program will have undefined behavior, but that’s a misuse of the API.

ShardedLRUCache Implementation

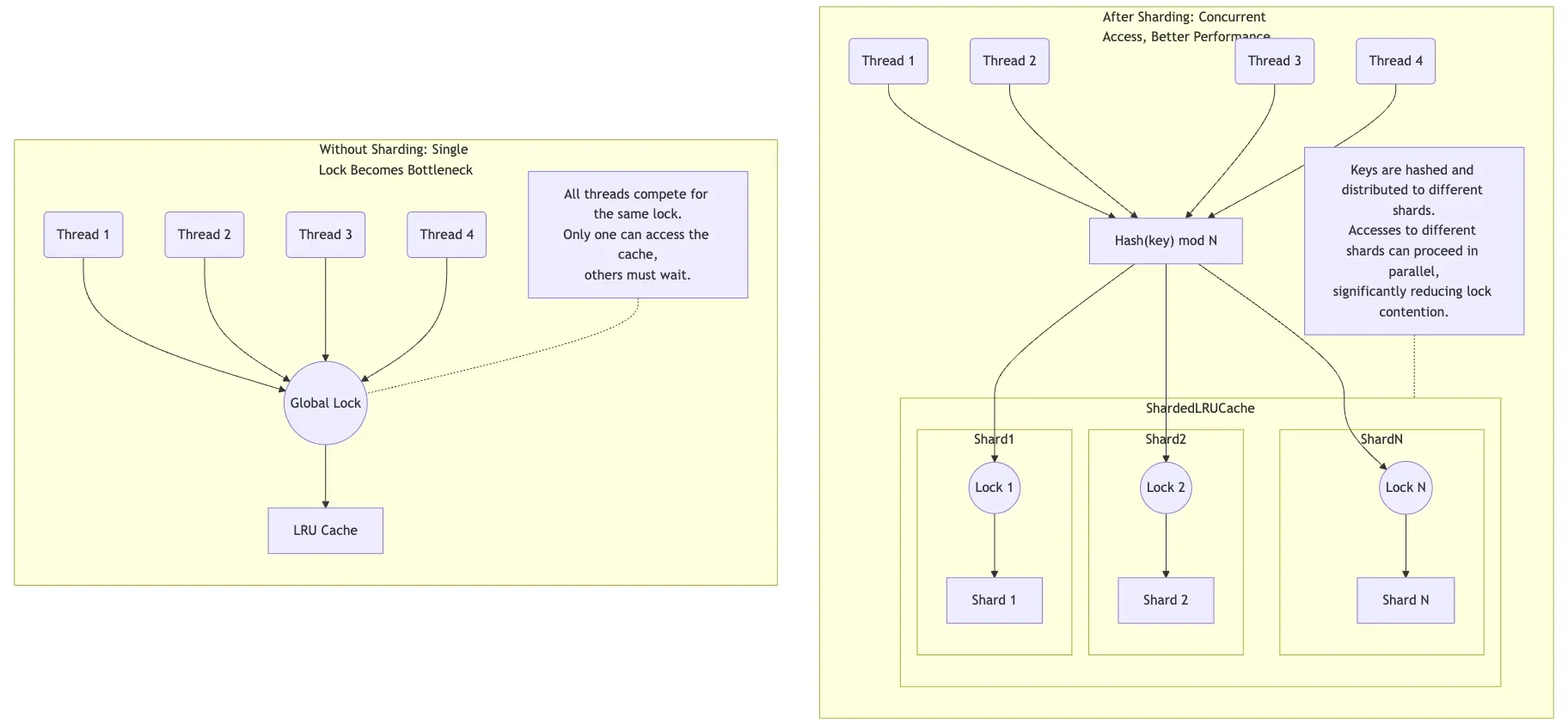

In the LRUCache implementation, insertion, lookup, and deletion operations must be protected by a single mutex. In a multi-threaded environment, if there’s only one large cache, this lock becomes a global bottleneck. When multiple threads access the cache simultaneously, only one thread can acquire the lock, and all others must wait, which severely impacts concurrency performance.

To improve performance, ShardedLRUCache divides the cache into multiple shards (the shard_ array), each with its own independent lock. When a request arrives, it is routed to a specific shard based on the key’s hash value. This way, different threads accessing different shards can proceed in parallel because they acquire different locks, thereby reducing lock contention and increasing overall throughput. A diagram might make this clearer (Mermaid code is here).

ShardedLRUCache Implementation

ShardedLRUCache Implementation

So how many shards are needed? LevelDB hardcodes , which evaluates to 16. This is an empirical choice. If the number of shards is too small, say 2 or 4, lock contention can still be severe on servers with many cores. If there are too many shards, the capacity of each shard becomes very small. This could lead to a “hot” shard frequently evicting data while a “cold” shard has plenty of free space, thus lowering the overall cache hit rate.

Choosing 16 provides sufficient concurrency for typical 8-core or 16-core servers without introducing excessive overhead. Also, choosing a power of two allows for fast shard index calculation using the bitwise operation .

With sharding, the original LRUCache class is wrapped. The constructor needs to specify the number of shards, the capacity per shard, etc. The implementation is as follows:

1 | public: |

Other related cache operations, like insertion, lookup, and deletion, use the Shard function to determine which shard to operate on. Here is insertion as an example, implemented here:

1 | Handle* Insert(const Slice& key, void* value, size_t charge, |

The HashSlice and Shard functions are straightforward, so we’ll skip them. It’s also worth noting that ShardedLRUCache inherits from the Cache abstract class and implements its various interfaces. This allows it to be used wherever a Cache interface is expected.

Finally, there’s one more small detail worth mentioning: the Cache interface has a NewId function. I haven’t seen other LRU cache implementations that support generating an ID from the cache. Why does LevelDB do this?

Cache ID Generation

LevelDB provides comments, but they might not be clear without context. Let’s analyze this with a use case.

1 | // Return a new numeric id. May be used by multiple clients who are |

For some background, when we open a LevelDB database, we can create a Cache object and pass it in options.block_cache to cache data blocks and filter blocks from SSTable files. If we don’t pass one, LevelDB creates an 8 MB ShardedLRUCache object by default. This Cache object is globally shared; all Table objects in the database use this same BlockCache instance to cache their data blocks.

In Table::Open in table/table.cc, we see that every time an SSTable file is opened, NewId is called to generate a cache_id. Under the hood, a mutex ensures that the generated ID is globally increasing. Later, when we need to read a data block at offset from an SSTable file, we use <cache_id, offset> as the cache key. This way, different SSTable files have different cache_ids, so even if their offsets are the same, the cache keys will be different, preventing collisions.

Simply put, ShardedLRUCache provides globally increasing IDs mainly to distinguish between different SSTable files, saving each file from having to maintain its own unique ID for cache keys.

Summary

Alright, that’s our analysis of LevelDB’s LRU Cache. We’ve seen the design philosophy and implementation details of an industrial-grade, high-performance cache. Let’s summarize the key points:

- Interface and Implementation Separation: By using an abstract Cache interface, the cache’s users are decoupled from its concrete implementation, reflecting the Dependency Inversion Principle of object-oriented design. User code only needs to interact with the Cache interface.

- Carefully Designed Cache Entries: The LRUHandle struct includes metadata like reference counts and cache flags. It uses a flexible array member to store variable-length keys, reducing memory allocation overhead and improving performance.

- Dual Linked List Optimization: Using two doubly linked lists (in_use_ and lru_) to manage “in-use” and “evictable” cache items avoids traversing the entire list during eviction, thus improving eviction efficiency.

- Dummy Node Technique: Using dummy nodes simplifies linked list operations by eliminating the need to handle special cases for empty lists, making the code more concise.

- Sharding to Reduce Lock Contention: ShardedLRUCache divides the cache into multiple shards, each with its own lock, significantly improving concurrency performance in multi-threaded environments.

- Reference Counting for Memory Management: Precise reference counting ensures that cache entries are not deallocated while still referenced externally, and that memory is reclaimed promptly when they are no longer needed.

- Assertions for Correctness: Extensive use of assertions checks preconditions and invariants, ensuring that errors are detected early.

These design ideas and implementation techniques are well worth learning from for our own projects. Especially in high-concurrency, high-performance scenarios, the optimization methods used in LevelDB can help us design more efficient cache systems.