LevelDB Explained - A Step by Step Guide to SSTable Build

0 CommentIn LevelDB, when the key-value pairs in the in-memory table (MemTable) reach a certain size, they are flushed to disk as an SSTable file. The disk files are also layered, with each layer containing multiple SSTable files. During runtime, LevelDB will merge and reorganize SSTable files at appropriate times, continuously compacting data into lower layers.

SSTable has a specific format for organizing data, aiming to ensure data is sorted and can be looked up quickly. So, how does SSTable store these key-value pairs internally, and how does it improve read and write performance? What are the optimization points in the implementation of the entire SSTable file?

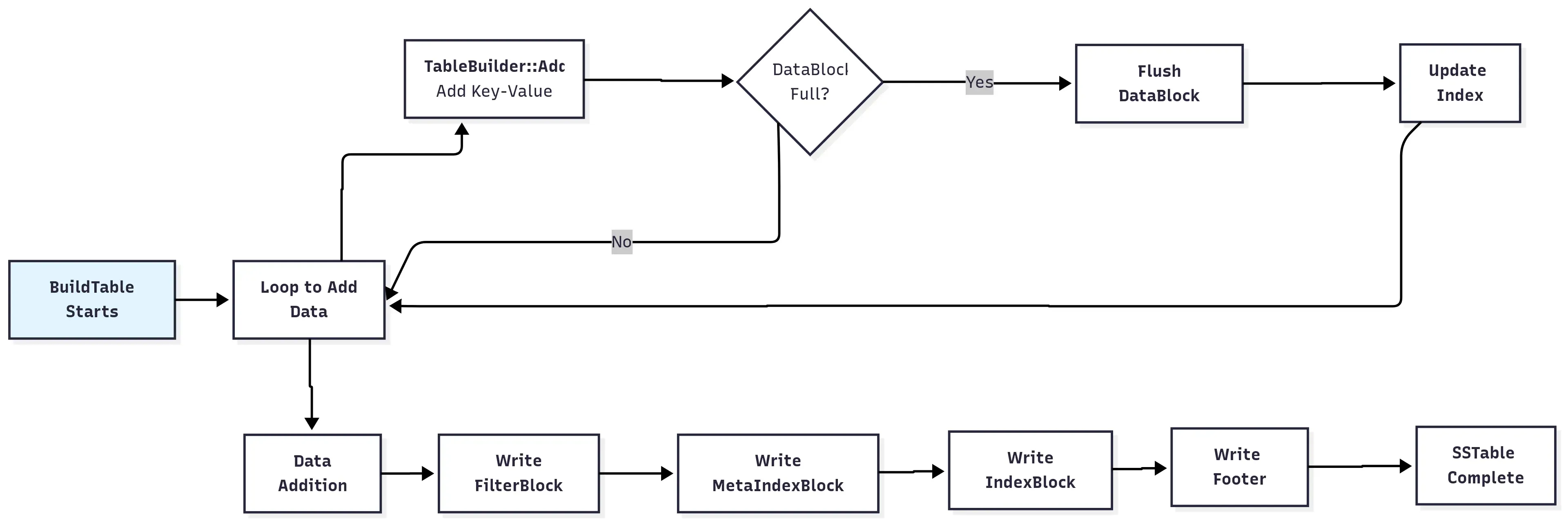

In this article, we will carefully analyze the creation process of SSTable files, breaking it down step by step to see how it’s implemented. Before we begin, here’s a high-level diagram to give you a general idea.

Overview of SSTable file building steps

Overview of SSTable file building steps

The Rationale Behind SSTable File Format Design

Before we start, we need to understand a key question: How should a file format be designed to balance efficient writes and fast reads? Let’s start with a few fundamental questions to deduce how the author designed the data format.

Question 1: How should key-value pairs be stored?

First, the core data, the user’s key-value pairs, needs a place to be stored. The simplest method is to put all key-value pairs sequentially into one large SSTable file. What’s the problem with this? First, when reading, if you want to find a specific key, you have to scan the entire large file. Second, during writes, if every key-value pair addition triggers a disk write, the write I/O pressure would be huge, and throughput would suffer.

Since a single large file is not ideal, let’s break it into blocks. The “divide and conquer” principle from computer science is well-reflected in LevelDB. We can split the large file into different data blocks and store key-value pairs at the block granularity. Each block is about 4KB by default. When a block is full, it’s written to the file as a whole, and then we start writing to the next one. Writing in larger chunks reduces a lot of disk I/O.

Let me add one more point here. Block-based storage not only reduces the number of disk write I/Os but also works in conjunction with…

However, the lookup problem isn’t solved yet. We still have to iterate through all the blocks to find a key.

If we could quickly locate which DataBlock a key is in, we would only need to scan a single block, which would greatly improve efficiency.

Question 2: How to quickly locate a specific Data Block?

To solve this problem, we need a “directory.” In computer science, this is called an index, and thus the Index Block was born. This block stores a series of index entries, each pointing to a Data Block. With this record, we can quickly determine which DataBlock a key belongs to.

This way, when looking up a key, we can perform a binary search in the Index Block to quickly locate the DataBlock where the key might be. Since the Index Block only contains index data, it’s much smaller and can usually be loaded into memory, making lookups much faster.

With the Index Block, we’ve transformed a full file scan into a “look up the index -> read a specific small block” operation, greatly improving efficiency. We’ll ignore the specific design of the index for now and analyze it in detail later.

Question 3: How to avoid unnecessary disk reads?

With the Index Block, we can find the block where a key might be, but it’s not 100% certain. Why? Because the Index Block only records key ranges, it doesn’t guarantee the key is definitely within that range. This will become clearer when we look at the code. This leads to a problem: what if we excitedly read a Data Block from disk into memory, only to find that the key we’re looking for doesn’t exist? That’s a wasted, precious disk I/O. This waste can be significant, especially in scenarios with many lookups for non-existent keys.

Computer science has long had a solution for this kind of existence check: the Bloom filter. A Bloom filter is a combination of a bit array and hash functions that can quickly determine if an element is in a set. A previous article in this series, LevelDB Explained - Bloom Filter Implementation and Visualization, provides a detailed introduction to the principles and implementation of Bloom filters.

LevelDB uses a similar approach. It supports an optional Filter Block. Before reading a Data Block, we can first check the Filter Block to see if the key exists. If it says the key is not present, we can return immediately. If it says the key might be present, we then proceed to read the Data Block for confirmation. This approach significantly reduces unnecessary queries for non-existent keys.

This all sounds great, but wait, there’s another problem. How do we know where the Index Block and Filter Block are located within the SSTable file?

Question 4: How to locate the Index and Filter Blocks?

So now we have many data blocks, an Index Block, and a Filter Block. Another question arises: when we open an SSTable file, how do we know the locations of the Index Block and Filter Block?

The most straightforward idea is to place this metadata at a fixed offset in the file. However, if we put it at the beginning of the file, any change to this metadata would require moving the entire file’s data, which is obviously not acceptable.

What about putting it at the end of the file? That seems feasible, and it’s how LevelDB is designed. At the end of the file, there’s a fixed-size 48-byte Footer area. It records the offset of the Index Block and another block we haven’t mentioned, the Meta-Index Block.

Logically, the Footer could just store the locations of the Index Block and Filter Block. Why introduce a Meta-Index Block? The author mentioned in the code comments that it’s for extensibility. The Footer has a fixed size and cannot be expanded to include more information. What if future versions need more types of metadata blocks, like statistics blocks?

So the author added an index for metadata—the Meta-Index Block. This block acts as a directory for metadata. Its keys are the names of the metadata (e.g., “filter.leveldb.BuiltinBloomFilter2”), and its values are the offsets of the corresponding metadata blocks (like the Filter Block). Currently, it only contains filter block information, but it can be extended to include any number of metadata blocks in the future.

This ties the whole lookup process together. First, we read the fixed 48 bytes from the end of the file. From there, we parse the offsets of the Index Block and the Meta-Index Block. Then, from the Meta-Index Block, we get the offset of the Filter Block. Finally, we read the content of the Filter Block based on its offset. With the Index Block and Filter Block, we can quickly and efficiently “follow the map” to find key-value pairs.

The Answer: SSTable Structure Diagram

Now that we’ve analyzed how data blocks are organized in an SSTable, here’s a simple ASCII diagram to describe the various blocks in an SSTable for better understanding:

1 | +-------------------+ |

However, providing the interface and saving key-value pairs in the above format involves many engineering details. By the way, the layered abstraction in LevelDB’s code is really well done, with one layer wrapping another, making the complex logic easy to understand and maintain. For example, how each block builds its data is encapsulated in a separate implementation, which I will detail in other articles.

In this article, we’ll focus on the engineering details of the SSTable file construction process. This part is implemented in table/table_builder.cc, mainly in the TableBuilder class.

This class has only one private member variable, a Rep* pointer, which stores various state information, such as the current DataBlock, IndexBlock, etc. The Rep* uses the Pimpl design pattern. You can learn more about Pimpl in this series’ article LevelDB Explained - Understanding Advanced C++ Techniques.

The most important interface of this class is Add, which in turn calls other encapsulated functions to complete the addition of key-value pairs. Let’s start with this interface to analyze the implementation of the TableBuilder class.

Add: Adding Key-Value Pairs

The TableBuilder::Add method is the core function for adding key-value pairs to an SSTable file. Adding a key-value pair requires modifying the various blocks mentioned above, such as the DataBlock, IndexBlock, and FilterBlock. To improve efficiency, there are many engineering optimization details. To better understand it, I’ve divided it into four main parts, which I’ll discuss one by one.

1 | void TableBuilder::Add(const Slice& key, const Slice& value) { |

Pre-checks

In the Add method, the first step is to read the data from rep_ and perform some pre-checks, such as verifying that the file has not been closed and ensuring that the key-value pairs are in order.

1 | Rep* r = rep_; |

LevelDB includes a lot of validation logic in its code to ensure that if there’s a problem, it fails early, a philosophy that is essential for a low-level library. The assert in the Add method here checks that subsequently inserted keys are always greater, which of course needs to be guaranteed by the caller. To implement this check, each TableBuilder’s Rep stores a last_key to record the last inserted key. This key is also used in index key optimization, which will be detailed later.

Handling Index Records

Next, it adds a new index record at the appropriate time. We know that index records are used to quickly find the offset of the DataBlock where a key is located. Each complete DataBlock corresponds to one index record. Let’s first look at the timing of adding an index record. When a DataBlock is finished, pending_index_entry is set to true. Then, when the first key of the next new DataBlock is added, the index record for the previously completed DataBlock is updated.

Here is the core code for this part:

1 | if (r->pending_index_entry) { |

The reason for waiting until the first key of a new DataBlock is added to update the index block is to minimize the length of the index key as much as possible, thereby reducing the size of the index block. This is another engineering optimization detail in LevelDB.

Let me expand on the background to make it easier to understand. Each index record in an SSTable consists of a separator key and a BlockHandle (offset + size) pointing to a data block. The purpose of this separator key is to partition the key space of different DataBlocks. For the N-th data block (Block N), its index key separator_key_N must satisfy the following conditions:

- separator_key_N >= any key in Block N

- separator_key_N < any key in Block N+1

This way, when searching for a target key, if you find the first entry where separator_key_N > target_key in the index block, then the target_key, if it exists, must be in the previous data block (Block N-1).

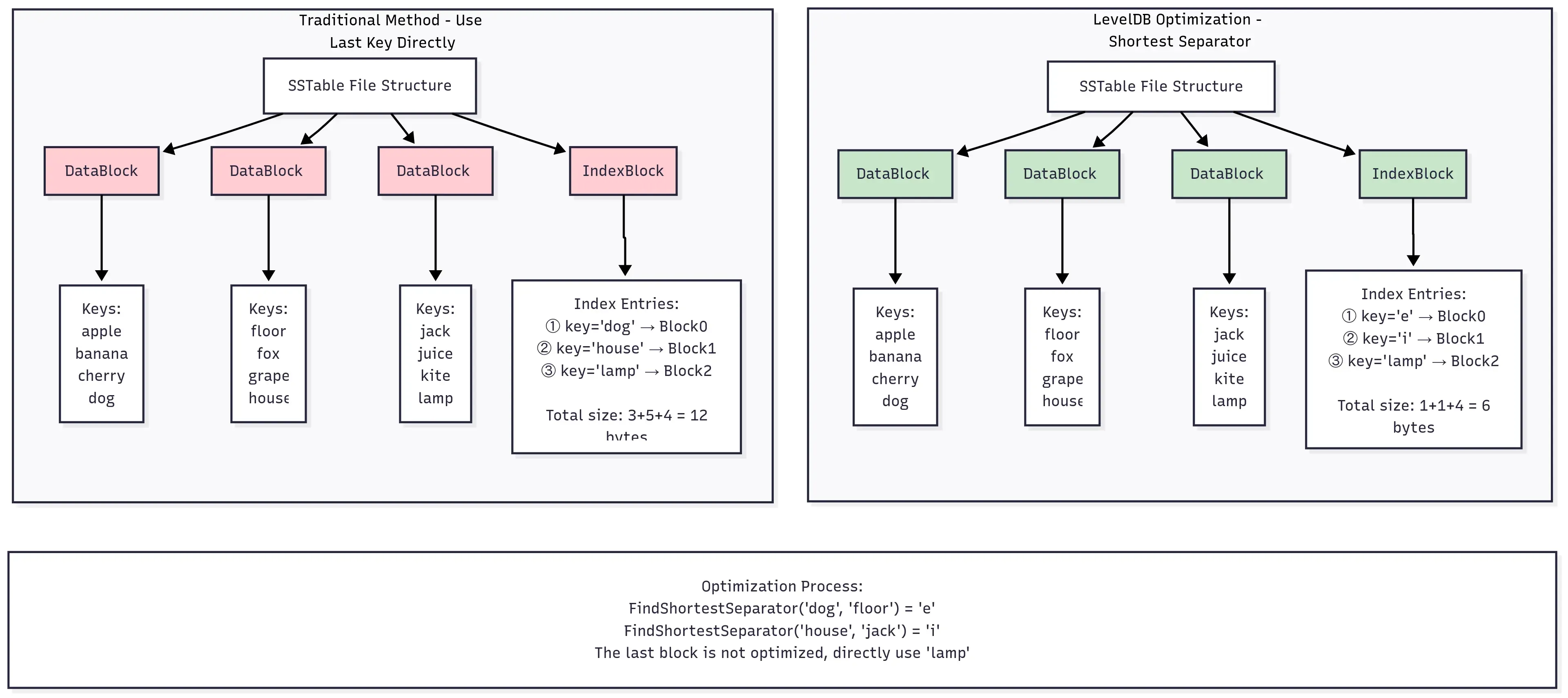

Intuitively, the simplest implementation of the index is to directly use the last key of Block N (last_key_N) as separator_key_N. But the problem is that last_key_N itself can be very long. This leads to long index entries, which in turn makes the entire index block large. The index block is usually loaded into memory, so the smaller the index block, the less memory it occupies, the higher the cache efficiency, and the faster the lookup speed.

If we think about it, we don’t actually need a real key as the separating index key; we just need a “separator” that can separate the two blocks. This key only needs to satisfy last_key_N <= separator_key < first_key_N+1. LevelDB does just that. It calls options.comparator->FindShortestSeparator to find the shortest separator string between the last key of the previous block and the first key of the next block. The default implementation of FindShortestSeparator is in util/comparator.cc, which I won’t list here.

To better understand this optimization process, here’s a concrete example:

SSTable DataBlock index separator key optimization

SSTable DataBlock index separator key optimization

Finally, let’s talk about the value of each index record here. It is the offset and size of the block within the file, which is recorded by pending_handle. When a DataBlock is written to the file via WriteRawBlock, the offset and size of pending_handle are updated. Then, when writing the index, EncodeTo is used to encode the offset and size into a string, which is inserted into the IndexBlock along with the preceding index key.

Handling Filter Records

Next is handling the FilterBlock. The index block we just discussed can only find the location of the block where the key should be. We still need to read the block’s content to know if the key actually exists. To quickly determine if a key is present, LevelDB supports a filter index block, which can quickly determine if a key exists in the current SSTable. If the filter index block is enabled, the index is added synchronously when a key is added. The core code is as follows:

1 | if (r->filter_block != nullptr) { |

After adding the key here, the index is only stored in memory. The FilterBlock is not written to the file until after TableBuilder has finished writing all the blocks. The FilterBlock itself is optional, and is set via options.filter_policy. When initializing TableBuilder::Rep, the FilterBlockBuilder pointer is initialized based on options.filter_policy, as follows:

1 | Rep(const Options& opt, WritableFile* f) |

It’s worth noting here that filter_block is a pointer mainly because, in addition to the default Bloom filter, you can also use your own filter through polymorphism. The object is created on the heap using new. To prevent memory leaks, the filter_block is deleted first in the TableBuilder destructor, followed by rep_.

1 | TableBuilder::~TableBuilder() { |

The reason rep_ needs to be deleted is because it was created on the heap in the TableBuilder constructor, as shown below:

1 | TableBuilder::TableBuilder(const Options& options, WritableFile* file) |

For the implementation of LevelDB’s default Bloom filter, you can refer to LevelDB Source Code Walkthrough: Bloom Filter Implementation. I will write a separate article to detail the construction of the index block, so we won’t go into the details here.

Handling Data Blocks

Next, the key-value pairs need to be added to the DataBlock. The DataBlock is where the actual key-value pairs are stored in the SSTable file. The code is as follows:

1 | r->last_key.assign(key.data(), key.size()); |

Here, the Add method in BlockBuilder is called to add the key-value pair to the DataBlock. The implementation of BlockBuilder will be described in a separate article later. Haha, LevelDB’s layered abstraction is so well done here that our articles have to be layered as well. After each key-value pair is added, it checks if the current DataBlock size has exceeded block_size. If it has, the Flush method is called to write the DataBlock to the disk file. The block_size is set in options, with a default of 4KB. This is the size before key-value compression. If compression is enabled, the actual size written to the file will be smaller than block_size.

1 | // Approximate size of user data packed per block. Note that the |

So how does Flush write to disk? Let’s continue.

Flush: Writing Data Blocks

In the previous Add method, if a block’s size reaches 4KB, the Flush method is called to write it to the disk file. The implementation of Flush is as follows:

1 | void TableBuilder::Flush() { |

The beginning part is just some pre-checks. Note that Flush is only for flushing the DataBlock part. If data_block is empty, it returns directly. Then it calls the WriteBlock method (detailed later) to write the DataBlock to the file, and then updates pending_index_entry to true, indicating that the index block needs to be updated when the next key is added.

Finally, it calls file->Flush() to have the system write the current in-memory data to disk. Note that this doesn’t guarantee that the data has been synchronized to the physical disk. The data might still be in the system cache, and if the operating system crashes, the unwritten data could be lost. For more details on file operations and flushing to disk, you can refer to this series’ article LevelDB Source Code Walkthrough: Posix File Operation Interface Implementation Details. If there is a filter_block, the StartBlock method also needs to be called. This method is also quite interesting and we will discuss it in detail when we specifically write about filter blocks.

WriteBlock: Writing to a File

As mentioned above, Flush calls the WriteBlock method to write the DataBlock to the file. This method is also called by Finish, which we’ll discuss later, to write the index block, filter block, etc., at the end. The implementation of WriteBlock is relatively simple. It mainly handles the compression logic and then calls the actual file writing function WriteRawBlock to write the block content to the file.

Compression is not mandatory. If compression is enabled when calling LevelDB and the compression library is linked, the corresponding compression algorithm will be chosen to compress the Block. LevelDB also strikes a balance between compression performance and effectiveness. If the compression ratio is less than or equal to 0.85, the compressed data will be written to the file; otherwise, the original data will be written directly. The actual file writing part calls the WriteRawBlock method, with the main code as follows:

1 | void TableBuilder::WriteRawBlock(const Slice& block_contents, |

Here, a 5-byte trailer is placed at the end of each block to verify data integrity. The first byte is the compression type; currently, the supported compression algorithms are Snappy and Zstd. The next 4 bytes are the CRC32 checksum. crc32c::Value is used to calculate the checksum of the data block, and then the compression type is also included in the checksum calculation. For more details on the CRC32 part, you can refer to this series’ article LevelDB Source Code Walkthrough: Memory Allocator, Random Number Generator, CRC32, Integer Encoding/Decoding.

Finish: Actively Triggering Disk Flush

All the operations above are mainly for continuously adding key-value pairs to the data block. If the DataBlock’s size limit is reached during this process, a flush of the DataBlock to disk is triggered. But the entire SSTable file also has an index block, a filter block, etc., which need to be actively triggered to be flushed to disk. So at what point is this triggered, and how is it flushed?

There are many occasions when an SSTable file is generated in LevelDB. Let’s take the flush triggered when saving an immutable MemTable as an example. When saving an immutable MemTable as an SSTable file, the process is as follows: first, iterate through the key-value pairs in the immutable MemTable, then call the Add method above to add them. The Add method will update the content of the relevant blocks. Whenever a DataBlock exceeds block_size, the Flush method is called to write the DataBlock to the file.

After all key-value pairs have been written, the Finish method is actively called to perform some finishing touches, such as writing the data of the last DataBlock to the file, and writing the IndexBlock, FilterBlock, etc.

The implementation of Finish is as follows. Before it begins, it first uses Flush to write the remaining DataBlock part to the disk file. Then it processes the other blocks and adds a fixed-size footer at the end of the file to record index information.

1 | Status TableBuilder::Finish() { |

The way the various blocks are constructed here is also quite interesting. A builder is used to handle the content, while a handler is used to record the block’s offset and size. Let’s look at them separately.

BlockBuilder for Block Construction

First, let’s consider a question: with so many types of blocks, does each block need its own Builder to assemble the data?

To answer this, we need to look at the data structure of each block. The Data, Index, and MetaIndex Blocks all share the following common features:

- Key-value structure: They all store data in a key-value format. Although the meaning of the keys and values in each block is different, they are all in a key-value format.

- Order requirement: The keys must be sorted because binary search or sequential scanning is required for lookups.

Therefore, the construction logic for these three types of blocks is similar, and LevelDB uses the same BlockBuilder to handle them. The implementation is in table/block_builder.h, and it also has many optimization details. For example, prefix compression optimization saves space by storing only the different parts of similar keys. The restart point mechanism sets a restart point every few entries to support binary search. I will write a separate article to detail this later. After encapsulation, it’s quite simple to use. Taking the MetaIndex Block as an example, you use Add to add key-values and then WriteBlock to flush to disk. The code is as follows:

1 | void TableBuilder::Finish() { |

On the other hand, the data structure of the filter block is different from the others. It stores the binary data of the Bloom filter, grouped by file offset, with one filter for every 2KB file range. Therefore, the construction logic of the filter block is different from the others and needs to be handled separately. The implementation is in table/filter_block.cc, which I will analyze separately later. Its usage is quite simple, as shown below:

1 | // Write filter block |

Here, the Finish method returns the binary data of the filter block, and then the WriteRawBlock method is called to write the data to the file.

BlockHandle for Recording Offset and Size

The two builders above are used to construct the blocks, but the same handler class is used to record the offset and size of the blocks. The code is as follows:

1 | BlockHandle filter_block_handle, metaindex_block_handle, index_block_handle; |

The implementation of BlockHandle is in table/format.h. It mainly tells the system that there is a block of size Y bytes at position X bytes in the file, and that’s it. However, in conjunction with the handle information of different blocks, it can conveniently store the offset and size of different blocks.

At this point, we have used two builders to construct various index blocks, and at the same time, used one handler to assist in recording the offset and size of the blocks. This completes the construction of the entire block.

Complete Steps for Creating an SSTable File

Finally, let’s see how the upper-level caller uses TableBuilder to construct an SSTable file.

A function BuildTable is encapsulated in db/builder.cc to create an SSTable file, which is implemented by calling the interface of the TableBuilder class. Omitting other irrelevant code, the core code is as follows:

1 | Status BuildTable(const std::string& dbname, Env* env, const Options& options, |

Here, an iterator iter is used to traverse the key-value pairs in the immutable MemTable, and then the Add method of TableBuilder is called to add the key-value pairs to the SSTable file. The size limit of the MemTable is 4MB by default (write_buffer_size = 410241024). When adding key-value pairs with TableBuilder, the data is divided into data blocks according to block_size (4*1024). Whenever a DataBlock is filled, the data of the corresponding block is assembled, and then appended to the SSTable file on disk using flush. Finally, the Finish method of TableBuilder is called to write other blocks and complete the writing of the entire SSTable file.

Besides BuildTable writing data from an immutable MemTable to a level-0 SSTable file, there is another scenario during the Compact process, where multiple SSTable files are merged into a single SSTable file. This process is implemented in the DoCompactionWork function in db/db_impl.cc. The overall flow is slightly more complex and the calls are deeper. We will analyze it in detail when we talk about Compact later.

However, let’s just mention one point here. During the Compact process, the Abandon method of TableBuilder is called in some failure scenarios to abandon the current TableBuilder writing process.

1 | compact->builder->Abandon(); |

Abandon mainly sets the closed flag in the TableBuilder’s Rep to true. The caller will then discard this TableBuilder instance and will not use it for any write operations (there are a bunch of assertions to check this state during writing).

Summary

Returning to the question we raised at the beginning, how should a file format be designed to balance efficient writes and fast reads? Through a deep analysis of LevelDB’s SSTable file creation process, we can see how the author solved this problem step by step. First, the SSTable data format design has several important design principles:

- Block-based storage: Splitting large files into 4KB DataBlocks makes them easier to manage, reduces unnecessary disk I/O, and facilitates caching of hot data.

- Index acceleration: Using an IndexBlock turns a “full scan” into a “directory lookup + precise read,” reducing the number of disk I/O operations.

- Filter optimization: Using a FilterBlock at the source reduces unnecessary disk reads, improving read performance.

- Centralized metadata management: The design of the Footer + Meta-IndexBlock ensures extensibility, making it easy to add more metadata blocks in the future.

In the implementation of TableBuilder, we also saw many engineering details worth learning from, such as:

- Index key optimization: Delaying the update of the index until the next block starts, and generating the shortest separator key using the FindShortestSeparator algorithm, significantly reduces the size of the index block. This optimization may seem minor, but its effect is significant with large-scale data.

- Error handling: The large number of assert statements in the code reflects the “fail fast, fail early” philosophy, which is crucial for a low-level storage system.

- Layered abstraction: The layered design of TableBuilder → BlockBuilder → FilterBlockBuilder makes the construction of a complex file format organized and orderly. Each layer has a clear boundary of responsibility.

- Performance balance: The 0.85 compression ratio threshold in the compression strategy reflects a trade-off between performance and effectiveness.

In fact, the design of SSTable answers several fundamental questions in storage systems. It uses sequential writes to ensure write throughput and an index structure to ensure read performance. It uses block-based storage, on-demand loading, and caching to handle massive amounts of data with limited memory. At the same time, it uses compression and filters to balance storage space and query efficiency, and layered metadata to ensure system extensibility. These are all classic designs that have been refined over many years in computer software systems and are worth learning from.

After understanding the creation process of an SSTable, you may have some new questions: How is data organized within a DataBlock? What is the process for reading an SSTable? How do multiple SSTable files work together?

The answers to these questions form the complete picture of the ingenious storage engine that is LevelDB. I will continue to analyze them in depth in future articles, so stay tuned.